Your Brain Can Do More Than You Think It Can, Says Science

In 2000, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published the results of a by-now famous research study examining the brains of London taxi drivers who had navigated the city’s streets for years. The researchers found that the part of the taxi drivers’ brains that deal with spatial relationships—the hippocampus—had grown in size and contained a higher number of neural networks. Essentially, the taxi drivers had changed their brains by navigating London so much.

It’s not just cabbies whose brains change and adapt through training. Our brains are anything but static. When we have new experiences and encounter unfamiliar ideas, clusters of neurons are formed and existing clusters connected with previously learned behaviors are strengthened. Through the right kind of training, our brains can adapt to perform at higher levels than many of us tend to think—pushing us past what we believe our “natural abilities” to be.

Getting (Way) Beyond The Baseline

For nearly 30 years, behavioral scientist K. Anders Ericsson has researched how training can produce exceptional levels of performance. One of his focused on memory. Ericsson and two colleagues recruited a college student, whom they referred to by his initials, S.F., with a normal IQ and memory. After listening to a sequence of numbers, he could recall around seven digits. Sounds pretty normal, right?

The researchers then put S.F. through the ringer in the form of several hundred hours of memory-enhancement training. By the end of it, S.F. had drastically exceeded the goal of the exercise, which was to double his “natural” benchmark and memorize 14 random digits, and actually proved capable of memorizing up to 82. Just to give you a sense of that, here are 82 random numbers. Go ahead—try to memorize them all:

2 4 7 9 3 6 2 5 3 2 6 8 9 1 1 0 3 6 3 2 6 1 7 3 4 6 2 7

9 0 1 4 9 7 8 2 5 2 3 5 1 7 9 2 8 4 5 2 7 9 2 1 4 0 5 9

6 3 7 0 5 2 7 9 5 6 6 8 2 1 7 2 0 8 6 4 8 6 9 5 2 1

You probably can’t, right? Of course not—you haven’t spent hundreds of hours practicing. The researchers attributed S.F.’s vast improvement of his memory to his use of mnemonic associations—such as converting random numbers into running times, for instance, so 247 became two minutes and 47 seconds—and to relentless training.

You Can Do More Than You Think You Can

The effects of training on memory performance have been replicated many times by numerous researchers. When behavioral scientists from Florida State University analyzed the decades of research in this area, they concluded that there is no “evidence that would limit the ability of motivated and healthy adults to achieve exceptional levels of memory performance given access to instruction and supportive training environments.”

Ericsson and others have found that continual training has similarly remarkable effects across a wide array of professions, including business, music, mathematics, and sports—turning otherwise ordinary people into experts capable of superior performance.

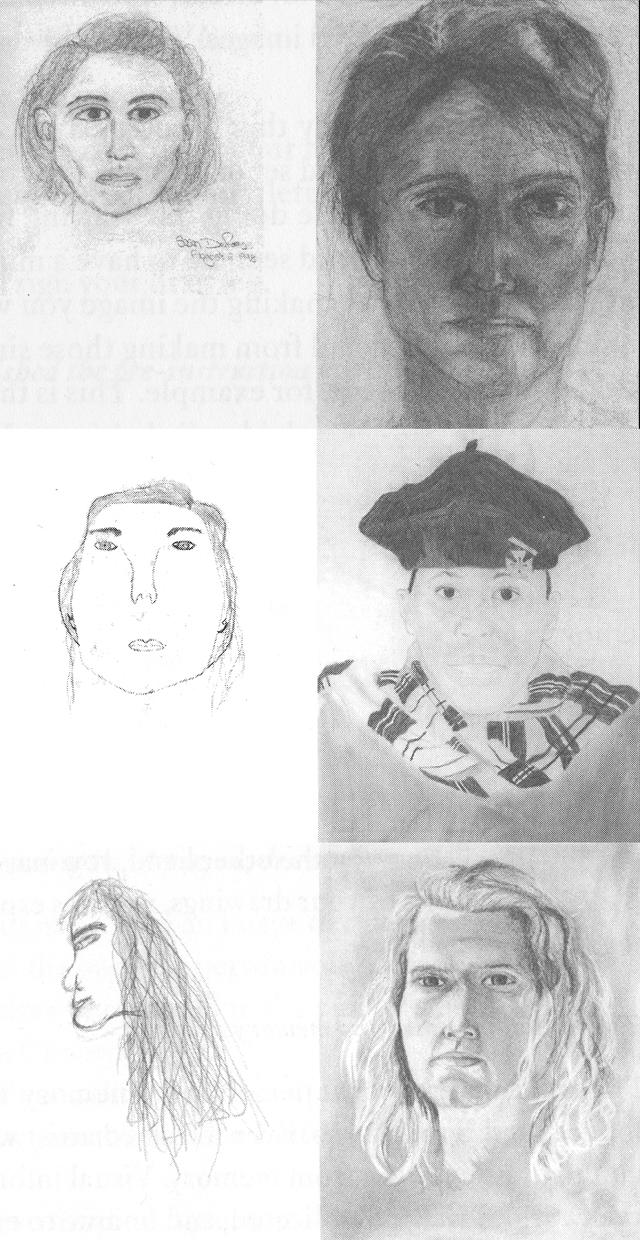

The renowned art teacher Betty Edwards made her name by taking people with ordinary artistic abilities and teaching them to draw impressive self-portraits. She accomplishes this feat not in years, months, or even weeks—she does it within a mere five days. In an updated 2009 edition of her landmark 1979 book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Edwards writes that once a person understands the technical components of drawing, he or she will progress rapidly—as long as they commit to focused practice.

Edwards emphasizes that most people don’t lack drawing skills as many believe they do, but rather seeing skills. She maintains that once she shows her students how to perceive things like edges, spaces, lighting, shadows, and relationships among objects, their ability to draw quickly improves. Here are some examples of the self-portraits her students drew on the first day of her class, and the same students’ drawings on day five.

Unfortunately, there’s no single approach to training that works across all disciplines. Every skill requires a different kind of development. But what the research shows is that what many of us believe to be the upper limits of our natural abilities may actually fall far short of them.

With diligence, focus, and time (and sometimes less of that than we’d imagine), our brains are wired to help us accomplish things we hadn’t previously thought possible. In fact, that’s one natural ability we all possess.

This article is adapted from The Science of Selling: Proven Strategies to Make Your Pitch, Influence Decisions, and Close the Deal by David Hoffeld, published by TarcherPerigee, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by David Hoffeld. It is reprinted with permission.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(7)