Abby Godee Thinks Companies Have Only Just Started To Truly Understand Design

“Only a tenth of the design capabilities are actually being utilized.”

How did you get to your position? What was the route that you took?

I’d like to say that my career did not follow a traditional route. In school, I studied more how different cultures create objects and processes to really reproduce their everyday life, so I’ve always been fascinated with everyday objects—housewares, things like decorative accessories.

My first job out of school was with Williams-Sonoma’s corporate headquarters, and I really loved it. That led to Smart Design in New York, and then later in San Francisco. At Smart Design, my journey was really about bridging the insights we’d gained about people’s everyday experiences with the growing significance that technology was playing in their lives. I spent more than 10 years at Smart, and worked for a lot of different clients in different industries, and gained a good breadth of experience.

And then I left Smart to do a short stint with Philips working in helping them figure out how to leverage design and innovation in their effort to create new ventures. It was a great learning experience.

Then I moved to Frog Design to lead the global AT&T account. It was a pretty unusual time when we were helping AT&T transform from a traditional telecom to more of a software company that was trying to fuel their growth with services across a broader ecosystem.

And then later, with Frog, I moved back to Amsterdam, where I essentially repeated that type of approach with several other companies—how to build on the value and expertise that a company has when it’s built its reputation more in the era of things and products, and help them create a significant place in the world of connected things, like services.

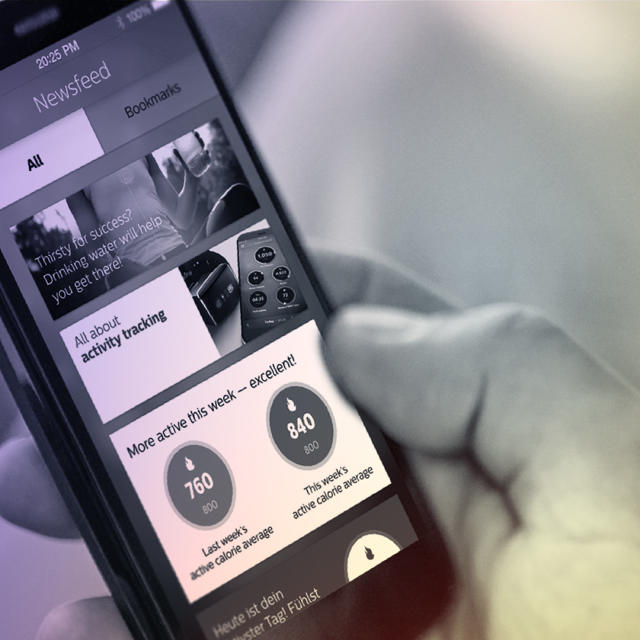

Then Philips approached me to help them with a similar challenge. And here I am at Philips, a company in transformation. In February, I was given an opportunity to lead design for our health care and schematics business as well as the personal health solutions business. And the point of all this was to specifically bridge the worlds of our clinical expertise and our consumer expertise through software experiences that would create more consistent and meaningful user experiences across that health continuum.

You’ve gone back and forth between working in a large company and working with agencies. Where do you see the differences there?

I think the differences are pretty dramatic. In the agency world, you get the advantage of being able to experience a lot of different industries and a lot of different challenges or problems in those industries. You can pick or spot the patterns that repeat, and you can really start to see how to apply the thinking in different industries and help people soak up the learning from different ways of working. The challenge is, within consultancy, you can’t really take it all the way through. On the corporate side, you have to be really good at understanding the strategy and how to build a vision that people can get excited about and want to sponsor.

What are some of the lessons you’ve learned?

There have been so many. One of the biggest themes is around alignment and creating a common language. I don’t think people in these programs generally spend enough time making sure that they’re saying the same thing. We have so much confusing language. And I have to say, design has been guilty of that a lot over the years—of creating specialized language to talk about what design does, reinventing words in order to explain things. And that’s not really doing us a lot of good. More often than not, we don’t spend enough time coming to common words to mean the same thing, and aligning on expectations.

Did you ever have a mentor or female role model?

I’ve had a series of them. When I was at Frog originally, and I’m not sure if it’s still the same today, but I was really inspired by the level of women leaders in the organization, and the way that everybody had their own distinct approach to communication and leading and decision-making. And what I love about it is that it is a bit of a sisterhood, in a way, of people that can actually rely on one another and talk to one another about things.

With a mentor, it’s a safe place to ask questions, like, “Does that ever happen to you, and how’d you deal with it?” Today I spend a lot of time trying to mentor the younger women.

You have the unique experience of working both in Europe and in the U.S. Are the sensibilities about design different?

I don’t think so. I think that’s one of the outcomes of globalization. I miss some of the regionalism that existed before globalization.

What do you think are some of the biggest trends in design now? For example, I feel like leaders are putting design into organizations just to check a box. But are designers being used effectively to drive real change?

I think that’s a fantastic trend, and I can look at Philips and say I was amazed that design sits on the management teams at each of the businesses. It’s more than a checkbox, which is one of the things I was so happy about when I got there, and one of the reasons I took the job.

But at the same time, we’re not yet at the place where the organization knows 100% how to work with design. And I’m not talking just about Philips; I’m talking in general. It’s so fanatically popular right now, the idea of design, and design thinking and having chief design officers. I think there’s still a lack of understanding and maturity around what it means to be able to effectively leverage it. So design’s still brought in too late, very often, still only a tenth of the design capabilities are actually being utilized, in some cases. So it’s very popular. But I am not sure it’s yet as effective as it could be.

Do you think sometimes design clashes with business goals?

I’ve never seen outright conflict except when we have poor alignment in planning. Very often, people say, “Well, I need some of that,” but they don’t know what to do with it. And it’s the same thing that’s said when companies go through that transformation of being more old-school technology companies to software companies. They don’t necessarily know how to incorporate software development into their processes.

Just as an example, in software, design needs to be a critical part of the requirement development process. If I get handed a list of requirements and am told to just start designing that, and please don’t question these requirements, because we know these are the right things to go build, I know that we’re headed for a problem. So that’s where conflicts are going to come up, because I know for the next several months I’m going to be questioning requirements, and wondering, Well, what problem is this actually solving?

Part of your job is leadership. You’ve got to present ideas that are different, ideas that the organization hasn’t done. And as much as people say they like change, people are horribly resistant to change. What are some of the techniques that you use?

One is: You’ve got to know who’s in the room, and what they need. Where are they going to see risk in the idea? So you need to start to really map: Who are you talking to? What’s going to make it a win for them to say yes to the idea, and what are they scared of? And how do you address that fear? So that’s a simple exercise if you know who your stakeholders are.

And I think there are some people who talk about not just user-centered design but stakeholder-centered design as well, and really taking those extra steps in the process to understand what it’s going to take for this idea to be successful within this organization. Because there’s crazy ideas, but they’re crazy ideas that have to work and land in that organization, not just somewhere out in the world. So it’s got to be personal for that business.

I think it’s about storytelling, too. And I think that’s something we talk about a lot today, but I think that the art of that is to understand how to make the story real enough, but not so real that the people in the room don’t feel like they can come help add to that story. So coming in with a fully finished, highly polished story that doesn’t leave anybody room to contribute to the narrative is often a mistake. I think keeping the fidelity of the story a little bit lower, and showing them where, ” . . . and here’s the part where you can help in making this story real.” Help people start to feel invested and feel like they want to champion that, and help make it real.

Designers are often mission-driven. They want to change the world, and they’re gung-ho. Do they ever run into walls and hold onto their beliefs so much that they can’t see the forest for the trees? How do you work with that? What are some skills there that you could use to open up people?

I think that’s a really great question, because I see it in people’s eyes so often. You start down a process where the scope of the project is to make the world a better place in some way or another. At Philips, we are lucky enough that there are a lot of those kinds of projects—I mean, our mission statement is to improve the lives of three billion people. So with that as a mission statement, it’s a natural fit for designers to come and say I want to help do that. It doesn’t mean that every project in its entirety is going to change the world, and there are a lot of things that we start that have to change sometimes midway through because of one business reality or another, or you find out that there were potentially two different efforts that were kind of doing similar things, and now we need to combine those and make it something that can get to market in a more reasonable way.

So the world is filled with the need to compromise on different things, and you have to really be clear with the designers. What are the couple absolute, definite things we’re going to hang onto here, and kind of go down with the ship trying, if we can’t get it in? And make sure that you’ve got the business to really understand that and share that vision also. Because it can’t just be this fight of design hitting the brick wall and fighting for something that the business doesn’t believe in or want, because you’re just pushing boulders uphill, and that doesn’t make anyone feel good.

But what I also think is, with designers, in the beginning of the program, really lay out for them what the risks and challenges and opportunities are, and be as transparent as absolutely possible, because if they’re left in a bubble to think that everything’s possible all the time, then you’re not doing them a favor. They can’t really help you solve the problem and shift with the changing needs of the program. It’s heartbreaking, sometimes, when you see that somebody might look at an effort and say, “Aw. It’s not nearly as good as I’d hoped it would be. It feels like too many compromises.” But you have to encourage and help them to see the long view, that this one solution isn’t the end of the story. As a company—any company today that’s working in this kind of space—it’s the beginning of the story, and you’re going to build this over time, and you’ve got to show them how to make the effort what they believe it should be over time, and keep people’s spirits up and see how they can contribute to that.

What have you learned from leading all these creative people? What are some of the things that have made an impact on you?

I think it’s being really, really, super clear, being gentle. I think sometimes I’m very direct. I’m a pretty direct communicator, so making sure that I’m being direct and gentle in equal doses. And listening probably three times longer than I think I need to. So pausing a lot before I jump in and offer an opinion—really, really leading it out of people, and getting them to really tell me more and more about what it is they’re thinking and what they feel the solution could be, or what the problems really are that they’re trying to grapple with. Also being really decisive and clear when you need to make a decision. So if there is still room to explore, encourage it with gusto, but if there really isn’t, then be clear and focus the team so that they feel that their contributions are actually going to matter and that they’re not spinning their wheels.

Do you think being a woman makes your job harder, easier, or does it really matter?

Until recently, I haven’t really identified with being a woman in business. I just thought, Well, this is who I am, and I work in complex organizations, and doesn’t that make it complicated for everybody? So I haven’t really overidentified with the part of my journey that’s related to being a woman, but I do see that I’ve always worked in businesses and in roles where I’m one of one or two women in the room. That’s really not that unusual. And in some ways, it’s been great, because I find it makes it easier to be heard in a way, because you really are different than everybody else in the room. You can offer different perspectives.

And in other ways, it’s been a little bit of a challenge. I think a lot of times in business that what I consider to be more male traits are valued over what are considered to be more female traits. And I don’t mean to stereotype them, but I think the KPIs that the organizations use to judge people’s success, they need to evolve with a more progressive sense of leadership. I have a lot of women who come to me and say things like, “Well, I’ve been told in my review that I need to show more visible leadership.” What does that mean? What’s the code for that? And how does that affect people who maybe are more interested in the whole team being successful than highlighting individual success? Or for people who are more introverted than extroverted? So I don’t see these issues as just being women’s issues; I see them being just people who have leadership styles that are not that classic more extroverted, more expressive type of leader.

Approaches that seem to work, but are not really yet valued in business, or are still thought about as “soft skills”—empathy, emotional intelligence—how much do you use those? And is that accepted in the business world?

I use those skills every day. I think that it’s made me more approachable to the teams that I work with, and I think that that’s been a really good thing. So I know I get a lot of really positive feedback that the people who work with me, report to me, are part of the organizations that I’m helping lead, they often say, “We feel that you’re more accessible; we feel we can talk to you about things.” So that’s clearly resonating with people, and I think that that is more of a female approach, just being open to listening to things, even if it isn’t necessary on a critical path to some problem I’m trying to solve currently.

Being open to that conversation and that dialogue about the situations around our work, not just the work itself, I don’t think that that’s the part of the job that I’m getting evaluated on, though. I think it has a lot of good intangible value, but I don’t yet see that in the way we evaluate our leaders. The positive thing is when we see people having KPIs associated with talent retention. So there are other aspects to it that you can say, “Okay, that work that I do, that’s maybe more about emotionally engaging with people and having empathy for the way people are working,” that probably comes out in having people want to stay in the group longer and develop through the ranks of the group.

Do you feel like you use those emotions then? Do you think that the KPIs over time will change?

I think it’s going to take a long time, because it’s the perennial question of, “How do you measure the value of design?” It’s also, “How do you measure the value of soft skills?” And I think that business is hard-wired to want to have things they can measure. They embrace things that can be measured. I think if we can start figuring out how to measure the value of the soft skills, I think it’s going to be easier for business to make sure that it’s embraced. But also, always having to find a measurement for everything when it seems as plain as the nose on your face that it matters can be a conversation that doesn’t really go anywhere.

That’s also why I like the qualitative research and quantitative research, because you can start to correlate on things, and give people at least a stronger sense of confidence that something works. But that’s another topic.

Sometimes people need proof that something like this works. You can’t just say it, even though it feels good and you know instinctively that it works.

But they also need belief. And if we had stronger anecdotes about why it works, we could build more belief. Because I think sometimes it goes back to the storytelling and the anecdotes and being able to create a sense of what the truth is for people: “Well, look. I lived it. I felt it. I saw this happen.” And you have people supporting that opinion, and it starts to become the truth for people. They start to just believe it. And I don’t mean that you’re pulling the wool over anyone’s eyes; it’s just that you have to really make the story accessible to them so they understand it.

If you weren’t doing this, what would you be doing?

There’s a woman who started a business years ago out of Santa Cruz where she works with local organic farmers and producers of amazing food, and she puts on these 300-person dinners with these mile-long tables that you can sit at. I wish I’d had that idea. I guess I love entertaining, and I’ve always thought that I’d love to create a business that brought together people and food and discussion and entertainment—sort of the TED of dinner parties.

I know you love to cook. Is that your creative outlet?

Oh my God, yes. And my creative masterpiece is my new kitchen. I have just created a kitchen that dwarfs the rest of my house.

I know we can’t hug in the workplace, but are you a hugger?

We don’t hug in the workplace in the Netherlands because Dutch people don’t typically hug. But we kiss in the workplace once a year, and that’s the first day that everybody comes back to work from the Christmas and New Year’s break. There’s always a little coffee corner where people get together and greet each other in the new year, and everybody runs around kissing everybody on the cheeks three times. And of course the following week, a lot of people come back to work with colds and the flu, but that’s what they like to do.

(117)