Can Finhabits Narrow The Wealth Gap Between Whites And Latinos?

Serial entrepreneur Carlos Armando Garcia was raised by immigrant parents in a Texas border town. Both parents worked, which instilled a strong work ethic in Garcia, who earned an engineering degree from MIT and later founded a hedge fund. “But when it came to thinking about money for the longer-term, for the future, we never had these conversations,” he says.

The same is true of many Latino families; only one in four has a retirement account, and just half own a home. As a result, the median net worth of Latino households trails that of white households by over $ 100,000. For black households, the statistics are similarly alarming. The most recent data, from 2013, shows that two-parent black families ($ 16,000) and two-parent Latino families ($ 18,800) are even worse off than single-parent white families ($ 35,800), in terms of wealth.

Income is certainly a contributing factor; whites have out-earned blacks and Latinos for decades. But Garcia believes that there are other factors in play, as well: “It’s about culture, habits, and access,” he says.

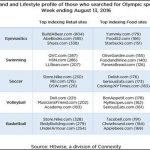

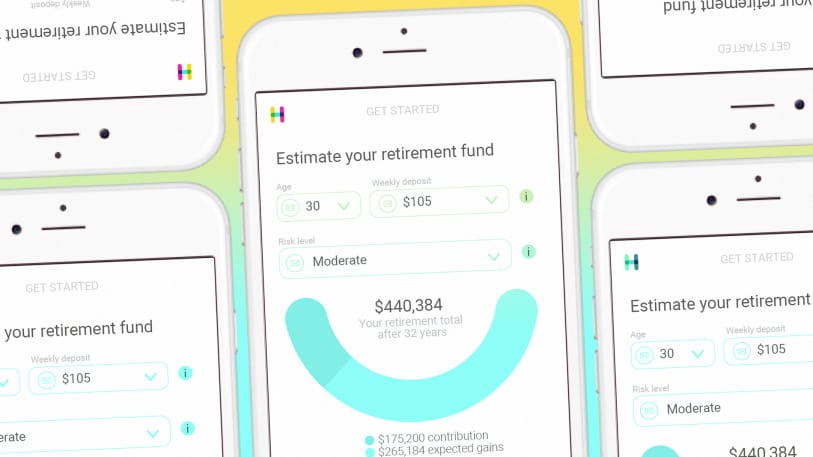

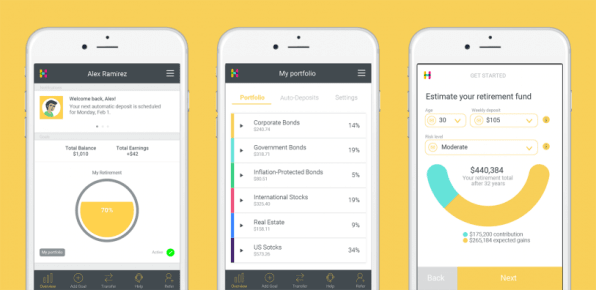

Now Garcia wants to help his fellow Latinos push back against those challenges and close the wealth gap. In February, he launched Finhabits, an online investing service designed for first-time savers. The company directs user savings toward traditional and Roth IRAs, with portfolio allocations based on the user’s risk profile, and charges $ 1 per month for accounts under $ 2,500 (above that threshold, the fee is 0.5% per year).

Digital investment advisors are a dime a dozen these days, with startups like Betterment and Stash competing alongside “robo” offerings developed by such industry stalwarts as Charles Schwab. Finhabits stands apart in two ways: its focus on Latinos (there is a Spanish-language version of the product) and its decision to reach those customers via their employers. By Garcia’s count, there are millions of minorities, including Latinos, working for small businesses that do not offer 401(k) benefits. According to the National Institute on Retirement Security, only 38% of Latinos (versus 62% of whites) have access to a sponsored retirement plan through their employer.

It’s still early, but Garcia has been encouraged by the startup’s progress. Finhabits is growing at 20% month-over-month, with the strongest headway in Texas. The majority of users are setting up recurring deposits, at an average of $ 40 per week. For users off to a slower start, Finhabits sends financial advice and reminder prompts via text.

“Expert advice should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their background and portfolio balance,” Garcia says.

Lucia Islas, a Texas resident born in Mexico, exemplifies the type of customer that Finhabits hopes to win over. “From a very young age, I was taught to work really hard,” she says. “But I don’t think I was ever taught to save and to think about the future.”

She adds, “My parents didn’t save for retirement. There’s this belief that God will take care of us.”

Islas landed her first part-time job at age 16, and after college, she began a career in fashion. She didn’t think about saving for retirement until she got married and soon became pregnant with her first child. Her parents, still working, have struggled to make the time to visit their granddaughters. “It got me thinking: What do we want our old age to look like?” Islas says. She and her husband signed up for a financial planning course offered through their church. “It taught us about how to save for retirement, what kinds of accounts we’re supposed to use to invest in our kids’ future. These are the kind of lessons that just aren’t passed down in our culture.”

For Garcia, the savings wake-up call came after college, during his first Wall Street job at Merrill Lynch. Two years in, a coworker mentioned that he had already set aside a healthy nest egg, thanks in part to the firm’s matching program. “Matched, what’s that? I didn’t know what it was,” he says. “It was a missed opportunity, and I don’t want that to happen to others.”

(44)