Can Startup College Minerva Reinvent The Ivy League Model For The Digital Age?

Levy Odera has made it his mission in life to find solutions to poverty. “I grew up in a relatively poor neighborhood with a relatively poor family in Kenya,” says the political science PhD, now an expert in international development.

Odera was dividing his time between on-campus lectures at the University of Florida and semi-annual trips to Kenya when, in 2014, he read an article in The Atlantic about Minerva, a San Francisco-based startup school with ambitions to reinvent the Ivy League for the digital age. In some ways, the school resembles an old-fashioned, elite university. Admissions standards value demonstrated leadership and academic achievement, and students live together in a dorm while following an undergrad curriculum that echoes the liberal arts, with broad-based majors like computational sciences. After the standard four years, graduating students earn a bachelor’s degree.

“We are now building an institution that has not been attempted in over 100 years,” CEO Ben Nelson told the magazine, as the school was preparing to welcome its founding class of 120 freshmen.

But in other ways, Minerva, which has raised $95 million in venture capital, breaks with tradition. The for-profit venture combines online courses with experiential learning that takes place as students rotate through seven different cities around the world. The annual cost, including room and board, is less than $30,000—a relative bargain when tuition alone at many top universities is nearing $50,000. Most notably for academics like Odera, professors can teach from anywhere with a broadband connection.

Odera was intrigued, but he already had a job. “I shelved it for a while,” he says. “Then, my wife got admission to a program at Penn State to do her PhD.” Like many modern dual-income couples, they faced a dilemma. Would one partner’s career have to take priority? And how would the decision affect their young son, now 20 months old? Odera packed the family’s bags for Pennsylvania and applied to Minerva.

This week, after in-person training at Minerva’s headquarters, Odera starts his new role as an assistant professor of political science. “The model allows me to stay at home with my wife and my son, and attempt to achieve a balance between work and family,” he says. Going forward, it will also allow him to take longer trips to Kenya, where he is deeply involved in a range of social ventures and research projects focused on socioeconomic development. For Odera, there is no downside to the unconventional academic arrangement: “I’m efficient when I’m working independently.”

Research increasingly supports the preference for working remotely, or telecommuting. One influential study published in 2014 found that employees who work from home are happier and more productive. Employees relish the ability to focus and the lack of a commute; employers, in turn, save on real estate and improve retention.

Yet in higher education, on-campus teaching remains the norm—and a major challenge for far-flung schools looking to attract a diverse set of faculty members. Many colleges and universities are rural and remote, a deterrent for younger academics. And even jobs at urban institutions can create headaches for couples trying to manage two career paths.

Adopting a structure that supports remote work has been a boon for recruitment and diversity at Minerva. In its first year, more than 800 candidates applied for eight professorships. This year, after quadrupling its instructional faculty, Minerva will employ professors in 20 cities and four countries.

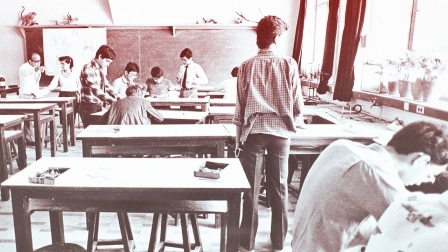

Traditionalists may balk at the idea of translating the kind of learning that currently takes place in storied seminar rooms and Gothic-style lecture halls onto laptops and smartphones. But Minerva, undaunted, has designed and engineered a technology platform that enables “fully active learning,” a pedagogy that dean of faculty Kara Gardner says is central to the student experience. For the full duration of each class, students and professor are on live video.

“There is no back row,” she says. “We don’t wait for volunteers; we call on students. They have to be at the ready for answering questions and on top of their preparation.” Plus, class sizes are small: Minerva caps each one at 19 students.

For some postdocs, the opportunity to focus on teaching in a more intimate setting than most top-tier universities can offer was enough to land Minerva at the top of their list of dream jobs. “I love teaching; I hate lecturing. It was a no-brainer for me,” says assistant professor Abha Ahuja, who studied biology and genetics and previously taught at Harvard Medical School.

Minerva’s geographic flexibility became an added benefit, freeing Ahuja’s husband, also a biologist, to apply for jobs at a broad range of biotechnology companies. They landed in San Diego and recently had their first child. “I don’t think I’m making a compromise, which is what often happens in these situations,” she says.

For associate professor Megan Gahl, an ecologist who lives in Juneau, Alaska, the ability to work from anywhere has given her family of four greater stability and her research a boost, thanks to nearby ponds and streams. “I can be in this remote place but have this very global experience,” she says.

Still, Gahl acknowledges that the model is not a fit for everyone. “You have to be able to self-motivate, and you have to be able to work on your own,” she says. “You can get this feeling that you’re very solo, up in Alaska at your computer. But you’re part of a larger piece.”

The one thing she misses from her years as an on-campus academic in Maine: Passing students in the hallways. “You have to make a little more an effort,” she says. “You have to actually make the connections happen.”

Outside of the digital classroom platform, professors and students also connect via Skype, Slack, and Facebook. Hardware helps, too: Assistant professor Randi Doyle swears by the giant Mac screen she installed in her home office. “I can see the students more clearly,” she says.

Doyle and her husband, who teaches elementary school, live on Prince Edward Island, where they both grew up. “The fact that I can live in this small town with all my family and work at an institution with the caliber of students that Minerva has, and also to have the deans and mentors I have—it’s too good to be true,” she says.

Having family nearby has come in handy. When an accident knocked out power for half of the island one day last school year, Doyle simply drove to her parents’ house, MacBook in tow. “I didn’t have my big screen, but it was just fine.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)