Climate change is killing off parasites. Here’s why that’s terrible news

As our planet grows hotter, we’re warned to expect a nightmarish dystopia full of melted ice caps, raging wildfires, acid rainstorms, and legions of diseases spread by bloodsucking ticks, gut-colonizing worms, and other germs. But in this rapidly changing world, a groundbreaking new study claims to have discovered a counterintuitive set of facts: Climate change appears to be decimating Earth’s parasites, and there’s a chance this could be worse for humans than the arrival of new microscopic protozoa.

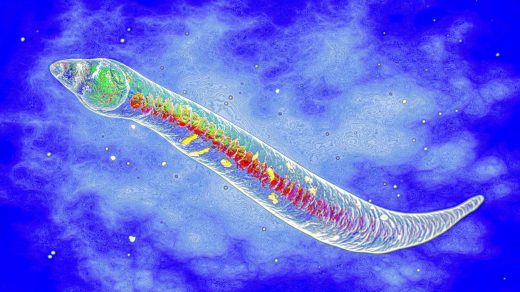

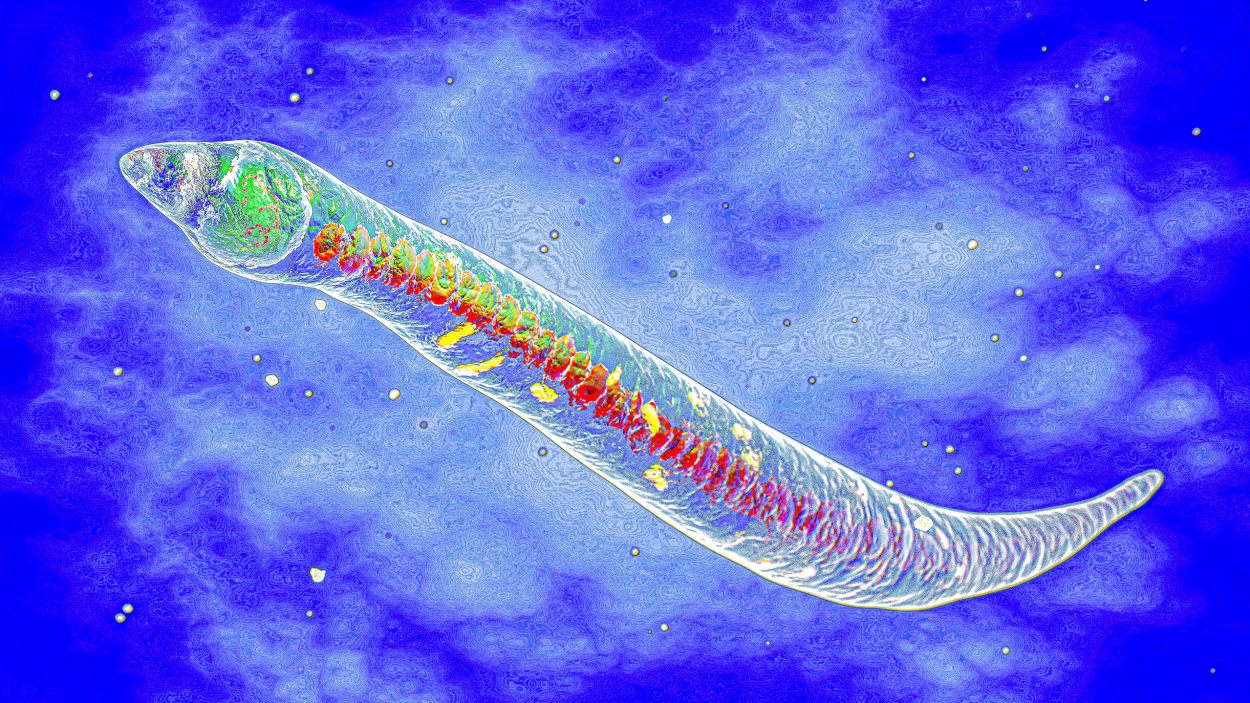

That is because, believe it or not, almost half of animal life on Earth is some type of parasitic organism. The word tends to invoke images of grotesque creatures that squat inside people’s or their pets’ intestines. However, that kind is actually rare—and the entire organism group plays a key role in keeping the planet’s ecosystems together. But according to a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they’re in the midst of a mass century-long die-off that tracks with Earth’s rising temperatures.

The study, led by a team of University of Washington parasite ecologists, analyzed the populations of some 85 parasitic species over time in Puget Sound, Washington’s inlet surrounding Seattle that serves as the second-largest U.S. estuary. The researchers used 699 fish specimens that were collected between 1880 and 2019 and preserved in formaldehyde, along with any parasites that hitched a ride. They tallied the year-over-year change, and discovered the number of parasites in Puget Sound has plummeted by 38% with every 1 degree Celsius that the surface temperature rose. The study, which is the largest, most comprehensive one ever conducted, concludes: “These data document one century of climate-associated parasite decline—a massive loss of biodiversity, undetected until now.”

Not enough is understood about parasites, and ecological surveys rarely consider their existence. A 2020 paper advocating for the creation of a Global Parasite Project database made its point by showing how hard it is right now to count just helminths—the big worm kind of parasite, usually visible to the naked eye—and the authors estimated anywhere between 100,000 and 350,000 species could exist, as many as 95% of which are “unknown to science.”

Parasites can kill their hosts, a fact that has provoked “justifiable concern that increasing parasite abundance could jeopardize conservation successes,” the authors acknowledge. But parasites also perform essential ecological functions in their ecosystems: “While a decline in parasitism might sound like a stroke of good luck, vital ecological functions could be lost.”

The point isn’t necessarily to launch a full-scale, save-the-parasites campaign—though a Ronin Institute parasitologist named Donald Windsor tried doing that in the ’90s with his catchy slogan “Equal rights for parasites!“—but rather to put their mass die-off in context. Take North America’s bird population, which decreases at a rate of about 6% per decade: There are several very big nonprofits established to save them. The specter of climate change causing a mass extinction event looks greater, when scientists admit that the extent to which Earth’s lifeforms rely on parasites may be underappreciated—and now, there’s new evidence they’re dying off faster than previously known.

“Parasites are hypothesized to be among the most imperiled species,” the authors note in their paper. These organisms aren’t just vulnerable to environmental change themselves—they’re doubly at risk, because so are the hosts they depend on to survive. And Puget Sound’s temperature change is actually quite small when compared to the ocean’s ecosystems that are experiencing the fastest rates of warming: Their temperatures have sometimes climbed by 2, or even 3 degrees Celsius in the past century.

(13)