Customized Or Creepy? Websites And Your Data, A Guide

Two visitors to the same news site see different headlines on the same article. Two potential donors see different suggested giving amounts on a charity website. A software vendor with free and premium versions keeps a list of “countries that are likely to pay.”

Those are some recent findings from the Princeton University Center for Information Technology Policy’s Web Transparency and Accountability Project, which conducts a monthly “web census,” tracking privacy-related practices across the Internet. Essentially, the project team sends an automated web-crawling bot to visit about 1 million websites and monitor how they, in turn, monitor their visitors.

Showing different versions of a site to different people isn’t inherently creepy, nor is monitoring what they do while visiting a website—without some basic monitoring and user segmentation, there would be no recommended products on Amazon or Netflix and no way for international websites to figure out which language users prefer.

And yet, some types of customization just make Internet users uncomfortable, and some may even risk crossing ethical boundaries. And so, without further ado, here’s a mostly unscientific guide to web-tracking practices in the wild, on a scale of 1 (not particularly creepy) to 5 (pretty creepy).

First-Party Cookies

If you’ve visited any European websites in the past few years, you’ve probably seen a little pop-up warning explaining that the sites use cookies—small text files stored by your browser with information about your activity on the site.

Under EU regulations, sites are required to let you know if they use cookies and allow you to opt out of having your browser store the files.

But despite the ubiquitous warnings, basic, first-party cookies, which are stored by a particular website you’re visiting and served back with each page on the site you load, really aren’t all that creepy.

First, sites are generally out in the open about their use of cookies—if there’s no European-style pop up, they’re often disclosed in reasonably plain English in privacy policies—and it’s easy to find instructions on viewing and deleting stored cookies in any major browser or on using private browsing modes to avoid storing them from browsing session to browsing session.

More importantly, first-party cookies are by definition tied to a particular website. They’re just a convenient way for programmers to keep track of information, like your user name or what’s in your shopping cart, that you’ve already provided to the site, often with the assumption that they’d store it.

A/B Testing

One reason different users see different editions of the same site or app is A/B testing—a practice where different users are purposely shown different versions of a site in order to measure which one is more effective.

The practice is a cornerstone of many modern, agile development practices, and of data-oriented business philosophies like Eric Ries’s “Lean Startup” methodology. It’s used by websites to test everything from quick color scheme tweaks to radically revamped algorithms for ordering social networking feeds. And modern Internet users are often accustomed to sites varying slightly from user to user, says Pete Koomen, cofounder and CTO of Optimizely, Optimizely, a San Francisco company that provides tools for customer segmentation and A/B testing.

“I actually think that at this point this is part and parcel of most users’ expectation of how the web works,” he says.

And yet, for particular sites, even sophisticated users can be unaware that there are multiple versions of the user experience, says Lisa Barnard, an assistant professor of strategic communication at Ithaca College who’s studied online marketing. And they can be disturbed to learn that even seemingly static content like news headlines can vary from user to user as part of an experiment.

“I teach students who are digital natives, they understand how this stuff works, and every time I tell them about A/B testing, they’re shocked,” Barnard says. “They realize that something’s happening [with targeted ads] because they know that they’re seeing something they were looking at before, but with something like A/B testing of headlines on a news site, there’s no tip off.”

And once they find out it’s been happening without their knowledge, they’re not always happy, she says.

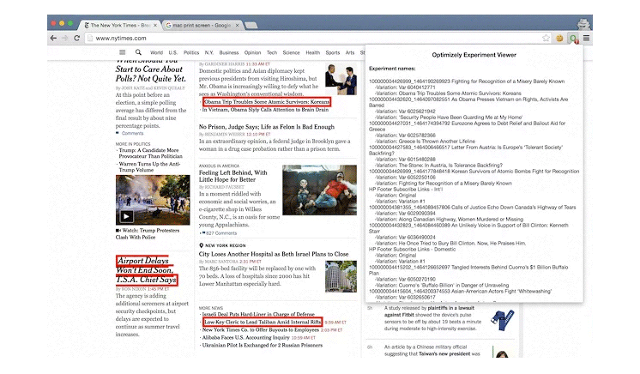

Among the information the Princeton researchers gather in their web census is the complete set of JavaScript code embedded in each page, explains project research engineer Dillon Reisman in a recent blog post. And on many sites, that includes code from Optimizely to implement A/B tests.

The team even built a Google Chrome extension—cheekily called Pessimizely—that can, depending on a website’s configuration, make it possible to see which segments of a particular web page are being tested and tweaked with Optimizely and how the page’s audience is being segmented.

Reisman emphasizes that there’s absolutely nothing wrong with using Optimizely, which boasts more than 6,000 corporate customers. But, he says, the findings still point to general unresolved questions about how transparent Internet companies ought to be about how they’re tracking visitor data and conducting user experiments, even if the practices themselves aren’t inherently negative.

To be clear, Optimizely doesn’t track users from website to website, explains Koomen.

“When a customer uses Optimizely to run experiments on their site, they only see the results of those experiments for their site alone,” he says.

For researchers and the public at large, Optimizely actually provides an unusually good look at how websites can vary from visitor to visitor, says Reisman. Customers can configure it to make testing variations and customer segment names visible for better integration with third-party tools, and the web census project and Pessimizely extension are able to access that data as well.

Reisman says he’d generally like to see companies more explicitly spell out all of the tracking, testing, and personalized tweaking they do, perhaps in their privacy policies.

“I’m grateful that that data’s there, because it’s so rare that you get to see what websites are doing when they’re A/B testing, and this actually is a very unique opportunity,” he says.

Third-Party Tracking Cookies

A little more off-putting are third-party cookies: cookies set by a website other than the site you’re visiting, which can help advertising companies and others track your behavior across the Internet.

Advertisers say these and other more complex tools for tracking users from site to site allow for better targeting of ads based on your browser history, but several studies have found consumers can find this more stalkerish than helpful.

A study by Barnard, the Ithaca College professor, found last year that ads that track users across websites can be perceived as “creepy” and sometimes make customers less likely to buy.

“They feel like companies know too much about them, and that they’re tracking them around the Internet,” Barnard says.”There’s something about that tracking that makes people uncomfortable, and, kind of, the uncertainty of how much these companies know about them and how they’re using it.”

And a Consumer Reports survey found most consumers unwilling to trade personal information for targeted ads and unconvinced such ads brought them more value. For those users, many popular browsers now contain built-in features to block third-party cookies.

Consumer Data Collection Tools

Cookies are data files stored by your browser, which means that if you’re aware of them and willing to do a little legwork, you can control if and when they’re stored.

But they’re not the only way for advertisers and website owners to track visitors from site to site. Clever—or creepy—programmers have found other ways to monitor your travels around the web that can be harder to detect and control.

The researchers behind the Princeton web census found websites using a variety of “device fingerprinting” techniques that allow them to identify visitors based on characteristics of their computers or phones, without having to store any data. For instance, websites—and advertisers—can examine the list of fonts installed on a computer or the exact output produced by a system’s audio or image processing software, which can vary from system to system.

It’s hard not to view these techniques, which are generally designed to circumvent users’ desired tracking restrictions, as intrusive. Luckily, at least one of the techniques, using characteristics of HTML graphics canvas elements to track users, appears to be on the decline after some public backlash, the researchers report.

“First, the most prominent trackers have by and large stopped using it, suggesting that the public backlash following that study was effective,” they write. “Second, the overall number of domains employing it has increased considerably, indicating that knowledge of the technique has spread and that more obscure trackers are less concerned about public perception.”

Still, while more legitimate websites may shy away from these techniques, it’s likely there will be a cat-and-mouse game for some time between shadier trackers and researchers who reveal their techniques.

Psychological Experiments

In 2012, researchers at Facebook and Cornell University tweaked a selection of users’ news feeds, showing them either a week of all positive stories or all negative stories. The immediate result? People who saw positive posts created more positive content of their own; people who saw negative stories posted more negative messages.

But the broader result was widespread condemnation of the project from across the Internet, including from the scientific community. Doing experiments with vague-at-best consent through website terms of service, with an eye toward influencing people’s emotional state, was widely denounced as unsavory, unethical, and potentially even dangerous.

“Deception and emotional manipulation are common tools in psychological research, but when they’re done in an academic setting they are heavily reviewed and participants have to give consent,” says data ethicist Jake Metcalf, a founding partner at ethics consultancy Ethical Resolve.

The company has since adopted and published new research vetting guidelines, influenced by those used in academic studies, and says it hopes they can be informative to other companies doing similar work.

“It is clear now that there are things we should have done differently,” Facebook CTO Mike Schroepfer acknowledged in a statement after the study came to light.

Surprising Price Variations

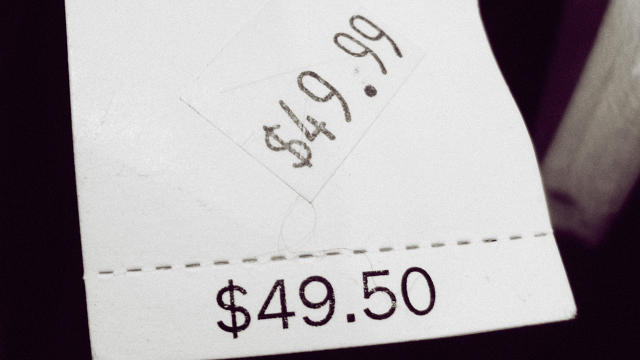

Last year, investigative journalism site ProPublica reported that prices of online test prep services booked through the Princeton Review’s website could vary by more than $1,000 dollars based on users’ zip codes. One result, according to the report, was that Asian users were more likely to be offered higher prices for tutoring services than non-Asians. The Princeton Review emphasized in a statement this was not its intent and that prices were based on “differential costs” and “competitive attributes” of different regional markets.

And in 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported that office supply chain Staples offered different prices to users in different zip codes and pointed out numerous other examples of online stores offering different prices, or discount offers, based on users’ location, device type, or other information, often to users’ frustration.

Also that year, the paper famously reported that travel booking site Orbitz was showing different lists of hotels on the first page of search results to Mac and Windows users, specifically showing higher-priced options for Apple users, who were found to be bigger spenders (though the company has emphasized particular hotels were priced the same for all users).

While differential pricing isn’t generally illegal, as long as there’s no discrimination against a protected class like a racial or religious group, it still often makes customers uncomfortable and anxious about whether they’ve truly gotten the best deal available.

“When that type of story comes out, people get upset,” says Barnard. “It’s that uncertainty that, I think, makes people really uncomfortable.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(68)