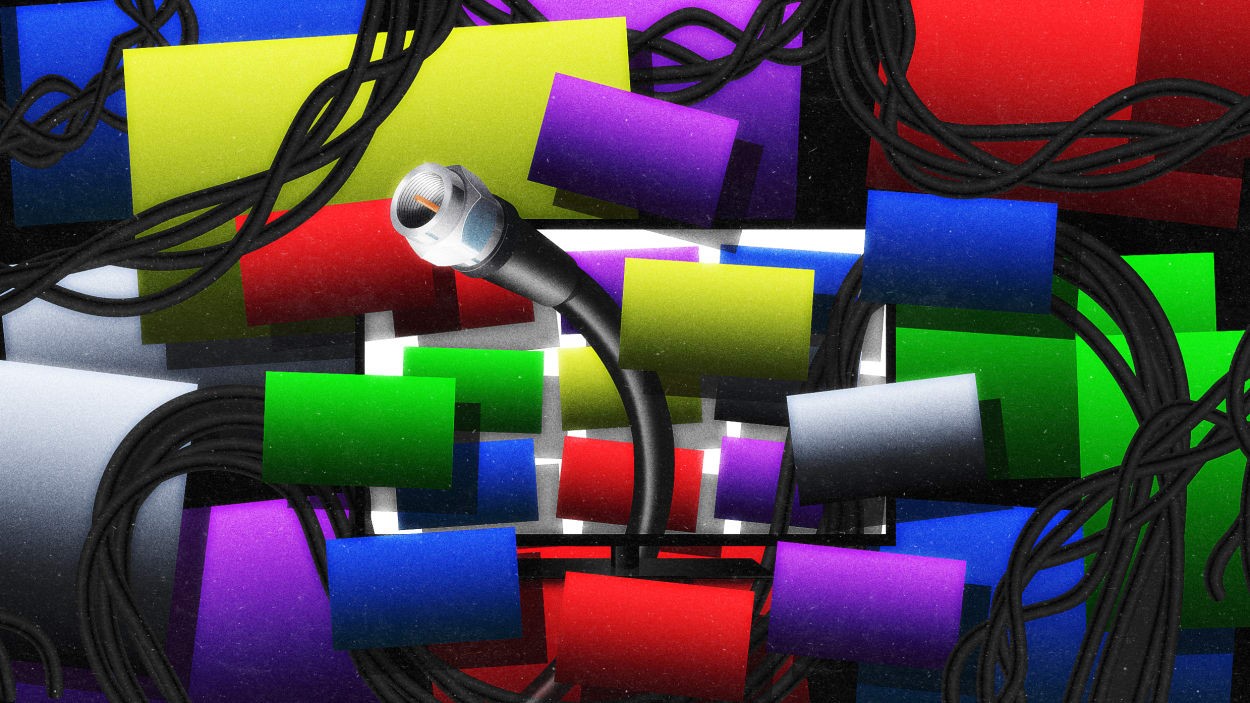

Cutting the cord was always a lie

By Mark Wilson

In September 2023, Amazon announced that it would begin including ads in Amazon Prime movies and shows. And today, that plan comes to fruition as the first unskippable ads debut on the service.

In a way, this moment is a relief. A tacit lie is now in the open. We’d all fallen for the premise that cutting the cord would lower our bills, allow us to skip commercials, and we’d still get to see all the shows we cared about—that Google TV was somehow distinct from Xfinity, and that streaming services were better than just turning on the television.

For a few years, perhaps, that premise was at least a little true. But now we’ve reached the culmination of capitalism. We never killed cable. We just cut it into a dozen pieces—streaming services, smart TVs, Rokus—that so often make our lives worse. The joyful UX of being a half-comatose couch potato is all but gone. And from the looks of things, it’s never coming back—not to your TV, at least.

The slow death of cable

Truth be told, the gold standard of cable has been gone for about 20 years now. In the pre-digital age, analog set top boxes were magical in that they were fast. With the press of a button, you were watching a new show. Not after a half-second delay. Not with a streaming buffer. It was instant. You were on a new channel before the button popped back up. “Channel surfing” became the UX of choice. You could check a programming guide to see what was on and when, but just changing the channel was often the quickest way.

Cable was the original all you could eat buffet of content, and a particularly scrumptious one for its plausible deniability. “Oh, I just put the TV on and The Office marathon was on! It’s not my fault I lost my weekend.” (Except back then it was MASH or I Love Lucy reruns or something.)

In the earliest days of cable, there were no ads. “WILL CABLE TV BE INVADED BY COMMERCIALS?” the New York Times asked in 1981. It was, of course. But instantaneous channel surfing lessened the sting, as many people casually watched a few things at once, hopping back and forth during the breaks (the modern day equivalent is like watching TV while being on your phone).

Cable still stunk in a lot of ways. The two shows you really wanted to watch during the week would inevitably be on at the same time, and that was never fun. But more so, you had to be in front of your TV when a show was on to ever see it, unless you wanted to mess around with programming a tape recorder. TiVo, the first major DVR, launched in 1999 largely to address this issue. It automatically recorded every episode of a show you wanted to watch, and by spending enough on hardware and other subscription costs, you could actually record multiple shows coming into your home at once. Even better? TiVo even had a built-in option to skip commercials with just a few presses of the button.

Trust me, youngest of millennials and Gen Zers. This was peak TV. Early TiVo was everything glorious about cable made better. (Even though, in retrospect, tasking millions of homes to individually record a stream of TV was completely nonsensical.)

Streaming services, which were more or less nonexistent before Netflix debuted the feature in 2007, were a natural evolution. Why have everyone record the same thing when you could just stream it from a central server?

Streaming solved real problems for viewers, too. It unearthed all sorts of shows and movies that had disappeared from the limited bottleneck of cable’s live channel distribution model. And it offered the chance to watch shows you hadn’t previously set to record, to treat movies and television with the instant gratification of YouTube (which launched in 2005) or Spotify (which launched in 2008).

Streaming rebuilt cable, with a more miserable UX

Since Netflix ditched DVDs to usher in the new era, streaming services have proliferated unmanageably, copy and pasting Netflix’s model to become something like cable networks you have to buy à la carte. Now, in terms of major players alone, there’s Hulu. Max. Peacock. Paramount+. Apple TV+. Disney+. And of course the aforementioned Prime Video. Which do you need to subscribe to in order to strike up a conversation with your coworkers? All of them! And none of them! But really, all of them some of the time. (Technically, the average is 2.8.) Whereas traditional cable bundled together these channels for us in a plan you set up once and forgot about—a painful bill that was at least easy to understand—now the onus is on the user to manage these subscriptions individually (each with their own login and password, of course).

Watching TV, the greatest of American pastimes, has become a source of emotional labor. I never know where any movie or show I want to watch resides, and ultimately I end up True Detectiving my way around Google to figure it out. I’ve found myself in a juggle of constant account activation and deactivation, anything to ensure another $15ish doesn’t fall through the cracks (but it always does). One of my greatest blunders was taking the bait with Hulu, and bundling my Hulu subscription with Disney+. Maybe I saved a buck a month in the process. But when I went to unsubscribe from one, it was impossible. So I had to quit it all and start over. Logins are digital trauma.

So what now? We’re already seeing hints of a Great Rebundling underway, like how Canada’s telecom company Telus is offering Netflix, Disney+, and Prime Video in a single subscription. But the lightning fast UX of cable, with its mindless pew pew pew of the remote, seems gone forever.

On TV at least.

Because when I consider the future of cable, and what cable looks like in the modern age of smartphones, I actually think its classic UX is alive and well. However, instead of television, we’re watching TikTok (or Instagram reels).

Sure, the channel changer has been swapped for the finger flip, and the studio shot programs have given way to influencers filming themselves on smartphones. Yet it’s still a form of democratized cable, albeit with a channel lineup determined by algorithms. There’s always another program to try with a flick. And most importantly, the plausible deniability of what you actually end up watching has returned in full, nonjudgmental force.

Which is just my very long way to say: Look, I didn’t choose to watch all these Matty Healy videos—they were just there in my feed!

(10)