From the U.S. Surgeon General: Anyone can be a healer

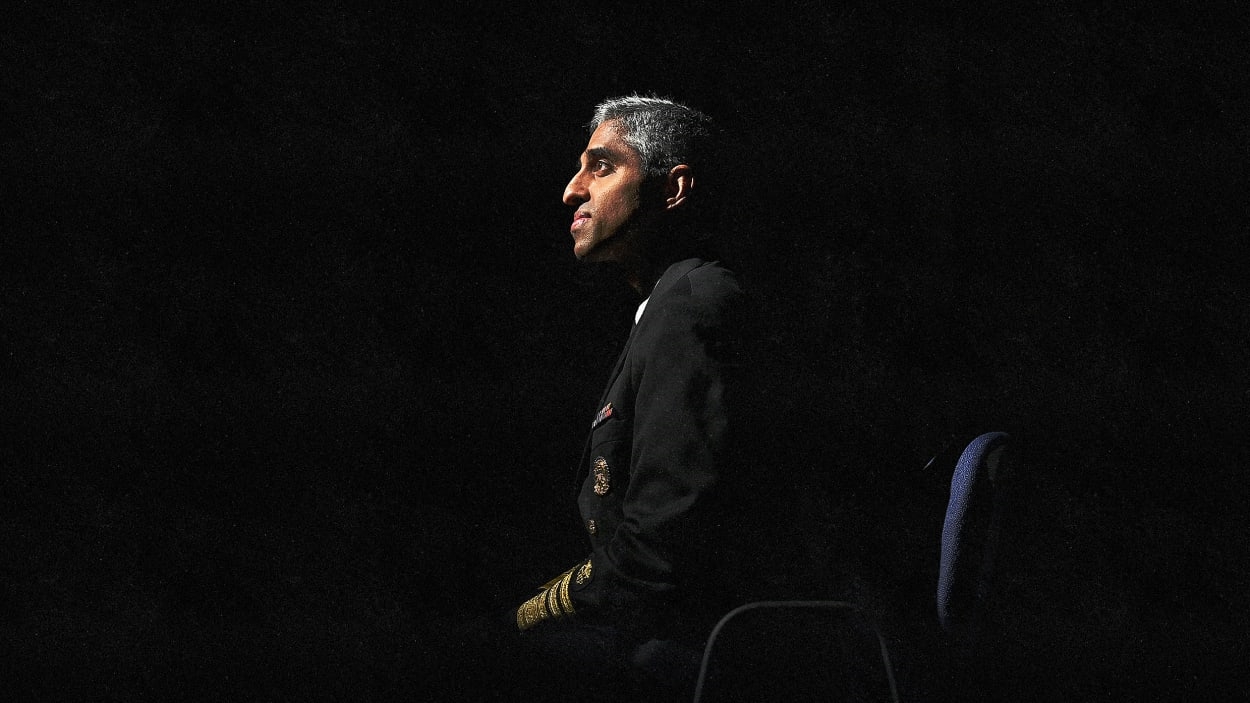

Serving as the U.S. Surgeon General, currently under President Biden and previously under Barack Obama, Dr. Vivek Murthy has led the nation’s response to a range of public health emergencies, including the Ebola and Zika outbreaks, the opioid crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet unlike his predecessors, who primarily tackled physical illnesses, Murthy is using his position as “the nation’s doctor” to expand the notion of what it means to take care of our health. He is spotlighting the growing mental health crisis in America, particularly among young people and in the workplace, while shedding light on the epidemic of loneliness and isolation. He is the author of the bestselling book Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World and hosts a podcast called House Calls, where he explores how we can “navigate the messiness and uncertainties of life to find meaning and joy.”

Murthy’s holistic approach to treating these often-overlooked public health issues is based on one of the main lessons he learned as a doctor: not just to treat the illness, but to treat the patient. Yet taking care of each other and our communities doesn’t require a medical degree. As Murthy says, we all have the capacity to be healers. Here, he explains how.

Fast Company: What inspired you to take this more holistic approach to care?

Vivek Murthy: I came to realize, both through my own life experiences and looking at the science, that mental health is health. It is a core component of our ability to function, be fulfilled, and show up for our family, friends, and community. Mental health is the fuel that allows us to be who we are and to do the things we need to do.

As a doctor, I saw the relationship between mental health and physical health. When people struggled with their mental health, it affected their physical health, and vice versa. It is long past time for us to erase this artificial distinction between the two. I have come to see, through my direct conversations with people all across our country and outside the United States, that there are millions and millions of people struggling with their mental health and well-being, and this crisis is getting worse, not better.

COVID-19 certainly added a lot of fuel to the fire, but this was a fire that was burning long before the pandemic. If we don’t change how we talk about mental health, make it okay for people to ask for help, make help available when people need it, and address the root causes of what’s driving the mental health crisis—then I worry that we will suffer as a society.

FC: You’ve discussed how loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling—that it poses harmful consequences that can be felt in schools, workplaces, and other organizations. Your most recent Surgeon General’s Advisory addresses the loneliness epidemic head-on. What led you to make this one of your highest priorities?

VM: Growing up, I struggled a lot as a shy kid who was introverted. I struggled to make friends and to find a community. I didn’t really know what the word loneliness meant, and I wouldn’t maybe have used that to describe myself, but in retrospect, it’s clear that that’s what I was dealing with. I also felt this real sense of shame thinking that something was wrong with me, or it was my fault that I was feeling lonely. And for that reason, I never really talked about it with anyone else, including my parents.

I came to see, over time, that this was not just an issue for me, but for the thousands of patients that I had cared for over the years, who would often talk about their struggles with loneliness when I would sit at their bedside and ask them about their lives.

When I came to serve as Surgeon General and had the chance to talk to people all across the United States, I came to see that loneliness is extraordinarily common. That’s what led me to dig into the science behind loneliness, which helped me to realize that not only is it common, but it’s extraordinarily consequential for our health. When people are socially disconnected, that increases not only their risk of depression, anxiety, and suicide, but also their risk of physical illness, cardiovascular disease, dementia, or premature death.

When people look back on what has given them the most joy, fulfillment, and meaning, it’s often the people—our relationships with our family, friends, and community. That’s what we have to get back to strengthening and rebuilding.

FC: What are some signs that a friend, colleague, or even a casual acquaintance needs help, especially if that person is naturally more reserved or introverted? How do you know when to reach out, and how do you figure out what to say?

VM: Loneliness can look different in different people. Some people’s loneliness manifests as withdrawal or being quiet. Other people may find that they’re more short-tempered or angry. What I would say is that if you have a friend who you notice is engaging less, it’s worth checking in to see how they’re doing.

A lot of time, I find that when I talk to people who are struggling with loneliness, nobody’s checking in on them or asking them how they’re doing. Sometimes, just showing up and being there for a friend to let them know that, “Hey, I care about you—I want to know how you are,” can mean a world of difference.

Number two is to recognize the power of listening. You don’t have to fix every problem that your friend is going through. Simply being there to listen can be powerfully validating and remind them that they’re not alone. Number three is to encourage friends to seek help if they’re struggling with depression or anxiety, which people are at increased risk for when they struggle with loneliness.

It’s still striking to me that, as far as we have come in eradicating the stigma around mental health, there’s still a sense of shame that people carry when they struggle with loneliness, depression, or anxiety. That makes it hard for them to ask for help. But encouraging your friends [to seek help] is a powerful thing you can do. In the United States, we have a relatively new emergency hotline for people who are struggling with their mental health. That’s 988—three simple digits. People can call or text if they need help in a crisis.

One last thing I would suggest is to share your own story. Sometimes, people think they’re the only ones going through loneliness, but a lot of us—if not most of us—have experienced loneliness at some point in our lives.

FC: Many of our readers at Fast Company are organizational leaders focused on well-being in the workplace. What are some practical steps that can everyone—from CEOs, to middle managers, to interns—can take to tangibly address this larger mental health crisis?

VM: Last year, I put out a Surgeon General’s Framework on workplace mental health. I laid out five essentials that managers and workplaces can focus on that can help create the kind of environment that supports mental health.

The first was protection from harm. We want to create environments where workers know they’re going to be safe. I say this especially because during the pandemic, for example, 80% of health workers were saying that they had been subjected to physical or verbal abuse.

The second is connection and community. We know that when people feel connected in the workplace, it positively impacts their retention, productivity, and engagement. That should matter to businesses because it matters to their bottom line and their ability to make an impact.

The third is work-life harmony. One thing that’s happened with the advances in technology is that work has crept more and more into our weekends, evenings, and vacation time. While that can seem like it’s contributing to efficiency, it also takes away from people’s ability to be there for their families and take care of themselves. So, drawing a firm line between work and non-work time can be very, very important.

The fourth is ensuring that people know that they—and their work—matter. Everyone wants to feel that they’re valuable, but sometimes we take it for granted that people just know that. They don’t always know that: They need to hear it from their managers and peers. People also want to know that their work matters. Knowing that your work matters isn’t always about saving a life somewhere. If I’m a custodian cleaning a school, my work matters because I’m creating a healthy environment for children to learn in, which is extraordinarily important. If I’m serving food in a cafeteria in an office building, I’m helping to provide people not just with nutrition and sustenance, but with human interaction that can bring joy to their days in small but powerful ways.

Finally, there’s growth. Everybody wants and needs to grow. They may differ in how they need to grow, but asking people about what their goals are for growth, or what ways they would be interested in growing, is important in keeping people mentally healthy and engaged in the workplace.

FC: As Surgeon General and Vice Admiral of the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, you command a uniformed service of over 6,000 U.S. public health officers. How are you implementing these lessons into your own life as a physician-leader?

VM: In our office, we have worked intentionally to create a culture where people know that their life outside of work matters just as much—if not more—than their life inside work. If they need to be there for their family, if they need to take some time to take care of their health, that’s what they should be doing.

I think this is a process of evolution for every workplace. We should always be asking, “How can we do better?” One thing we do is have one team member interview another for about 10 to 15 minutes during an all-hands meeting. These interviews are fun. They’re about the person’s life, the journey they’ve been on, what they wanted to be when they grew up, what they turn to during moments of worry or disappointment, and what gave them inspiration and hope over the years. They’re about who they are as people, not about their skillsets for their job.

I’m always struck by the power of these short interviews. For many of us, they’re our favorite parts of the week. They leave us feeling closer to people and more appreciative of them, and they ultimately impact how we work together in positive ways.

FC: You’ve always been committed to exploring the human dimension of medicine—even as a medical student. You helped establish an elective course called “The Healer’s Art” for this very purpose. What does being a healer mean to you now?

VM: I believe we all have the capacity to be healers, and you don’t need a medical or nursing degree to help another person heal. Being a healer is about seeing people clearly for who they are. It’s about being able to extend kindness, compassion, and love towards someone else. It’s about showing up for them during a time of need, even if that’s simply being there to listen while they go through something difficult.

In a time where so many people are struggling and suffering, it’s important for us to remember that inherent power we all have to be healers. If we recognize that, check on one another, and show up for one another, I think we can provide so much of the healing that the world desperately needs.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

(4)