Hitting the Books: How America’s Space Race sought to renew our ‘New South’

Welcome to Hitting the Books. With less than one in five Americans reading just for fun these days, we’ve done the hard work for you by scouring the internet for the most interesting, thought provoking books on science and technology we can find and delivering an easily digestible nugget of their stories.

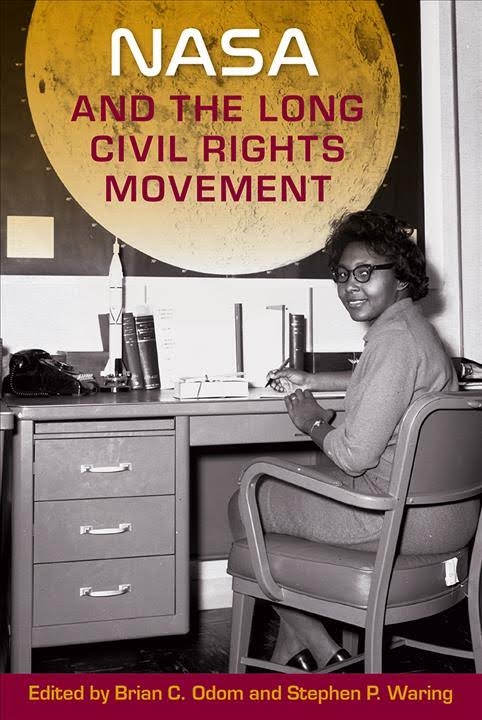

NASA and the Long Civil Rights Movement

Edited by Brian C. Odom and Stephen P. Waring

At its inception, NASA, and space exploration in general, was billed as an endeavor “for the benefit of all mankind.” However, the reality of the situation was far more messy. Eisenhower complained of the cost while leaders of the African American community questioned why we’d spend money on “space joyrides” rather than addressing more pressing planetside social issues.

At its inception, NASA, and space exploration in general, was billed as an endeavor “for the benefit of all mankind.” However, the reality of the situation was far more messy. Eisenhower complained of the cost while leaders of the African American community questioned why we’d spend money on “space joyrides” rather than addressing more pressing planetside social issues.

In the excerpt below from NASA and the Long Civil Rights Movement, essayist Brenda Plummer explains how the development of the Sun Belt — created in response to the USSR’s success with both Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin’s historic flight — was supposed to be the tide that lifted all boats. Instead, the creation of our aerospace industry in the land of Dixie actually helped to reinforce existing segregational lines with hierarchical class divisions.

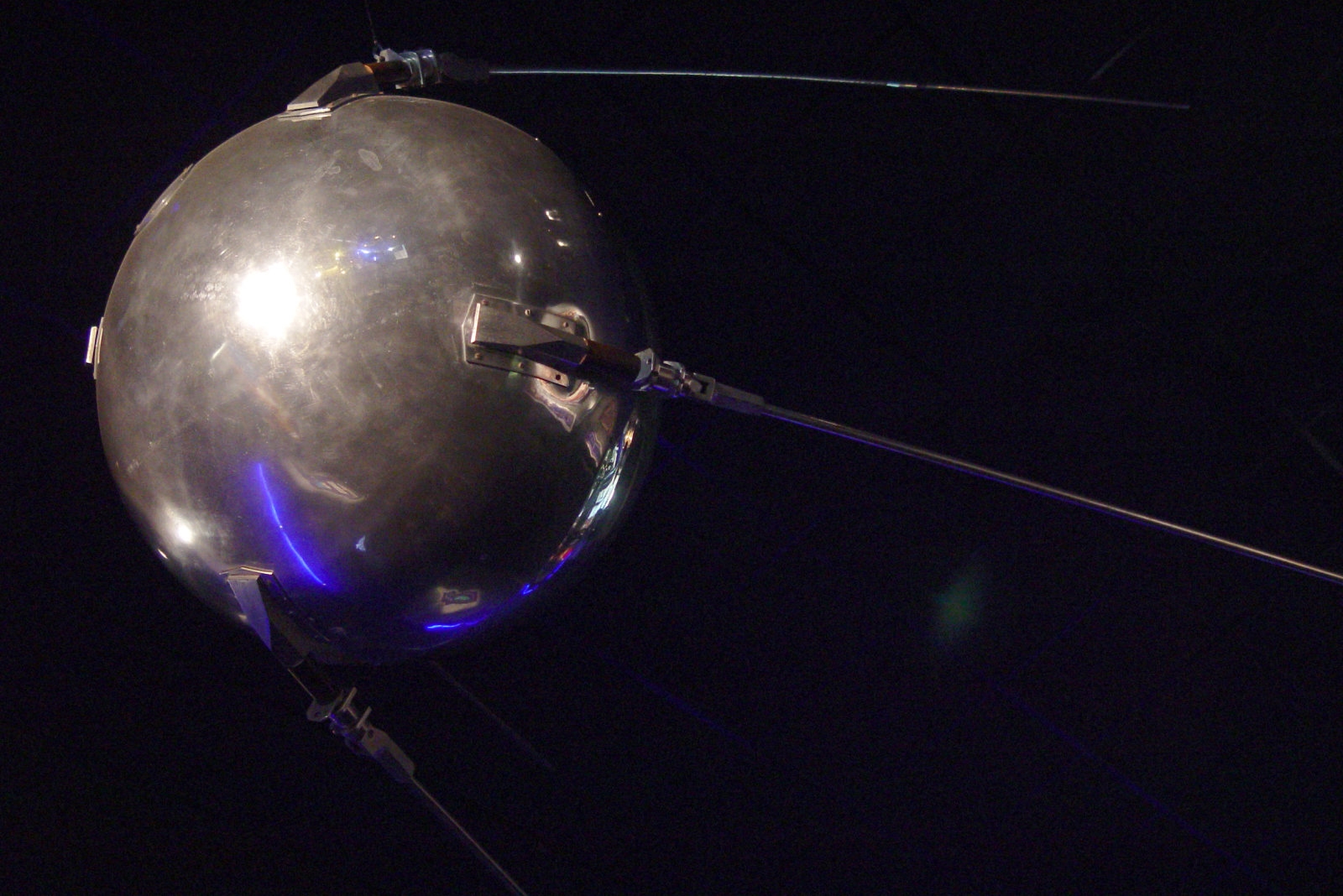

Sputnik had ushered in a feverish race to match the Soviets in space and provided an opportunity to criticize incumbent leaders’ presumed unreadiness. Texas senator and majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson, whose ambitions transcended regional identification, found an important role for himself both as a challenger of White House policies and an initiator of change. Senators Stuart Symington, Hubert H. Humphrey, and Estes Kefauver, along with New York governor Averell Harriman, launched rhetorical attacks on the Eisenhower administration with the assistance of Adlai Stevenson, presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956. They aimed to score successes for Democrats in the 1958 midterm elections and win the presidency in 1960 with a campaign, according to Stevenson, based on “the loss of our political prestige, Little Rock and our moral prestige.”

This approach energized the “scientists, intellectuals, and liberal pundits who had been marginalized as ‘eggheads,'” the historian Michael Curtin notes. These elements joined the call for greater military preparedness, better science education, and a rediscovery of national purpose. Steered through Congress by Johnson, the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 paved the way for the establishment of major scientific and industrial infrastructure in the South. Civil rights proponents used Sputnik to advocate equalizing opportunity in American society. Ending racial bias, they argued, would greatly enhance the nation’s ability to fulfill its democratic commitments and affirm its legitimacy as the leader of the West.

Cooperation from southern Democratic leaders was crucial to the success of any major changes in southern communities. Senator Richard Russell of Georgia opposed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, fearing that it would be used to deny funds to states with segregated public schools. Yet his stance on the federal presence in Dixie, like that of many other southern Democrats, was nuanced. Russell and such colleagues as Senator John C. Stennis of Mississippi, first chair of the new Senate Aeronautical and Space Sciences Committee in 1959, and John J. Sparkman of Alabama, a major proponent of missile development, had supported New Deal efforts to bring economic development to a region that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had called the nation’s number one economic problem. “States’ rights” had not been the rallying cry when it came to rural electrification and constructing army bases.

The momentum Sputnik achieved intensified when, in 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin made the first manned space flight. Soviet propagandists reprised the theme of solidarity with the colonized world with a poster proclaiming a “New Day” that depicted a black man bursting from his chains and saluting Gagarin as the Soviet pilot flew over Africa. Soviet geophysicist Yevgeni Fyodorov noted, “Comrade Gagarin saw the Congo where only recently Lumumba, the valiant champion of the happiness of the Congolese people, was heinously murdered.” Fyodorov and other Soviet celebrants linked the USSR’s accomplishment to a critique of Western imperialist exploitation of vulnerable countries and territories. The year before, when seventeen African countries became independent, the USSR established an Institute of African Studies within its Academy of Sciences.

Gagarin’s flight accompanied swift political and social changes in the United States. As Air & Space Magazine observed, “Gagarin’s Earth orbit, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, Alan Shepard’s flight, the Freedom Rides with their attendant violence and imposition of martial law, and Kennedy’s man-on-the-Moon-by-the-end-of-the-decade speech all happened within weeks of one another in 1961.” US officials were aware of the USSR’s determination to capitalize on the turn of events. “In seizing an early lead in space and following it with a series of dramatic successes,” the Central Intelligence Agency commented, “the Soviets have sought to bolster, both at home and abroad, claims of the superiority of their system.”

American leaders were thus determined to match the Soviets point by point. Just as the Soviets recruited their best scientists and technicians to the space effort, so did the Americans. In a move that recalled Gagarin’s exploit, astronaut Gordon Cooper Jr. orbited over Africa during his nearly day-and-a-half-long Project Mercury flight in 1963. He radioed salutations to the nascent Organization of African Unity. This was not simply a conventional diplomatic gesture. The United States found it easier to match Soviet gestures than to tackle the domestic race question head on. Both the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations were reluctant to fully invest in restoring the civil rights lost to blacks in the collapse of Reconstruction. Kennedy focused instead on Africa in a bid to mollify increasingly critical black voters. He could thereby nod to their concerns while avoiding a confrontation with segregationists. The approach also aimed at neutralizing for Africans the appeal of Soviet anti-imperialist rhetoric. It underlay White House invitations extended to African leaders and visits to African countries by astronauts Cooper and Pete Conrad.

Camelot-era symbolism belied, however, the very regional character of the space program and its associated economy. NASA built major facilities in southern states made attractive by favorable weather, prior histories of military base development, and a compliant population. Lyndon Johnson, first as a senator and later as vice president and president, worked hard to promote the agency’s mission as devoted to civilian control of aerospace research. Therein lay a benefit. As the historian Joseph A. Fry put it, “the space program went far toward fulfilling LBJ’s search for a mechanism for building a New South of ‘science and technologically-based enterprise.'” Beyond the conventional pork barrel associated with federal largesse was something more far-reaching: a fresh iteration of the New South.

Space and its management in a terrestrial sense played a part in the society NASA helped to produce. “The space age has arrived on the Gulf Coasts of Mississippi and Louisiana,” the New York Times proclaimed, “displacing people, stills, snakes, alligators, wild pigs, ducks, a graveyard and attitudes.” Scientists and engineers terraformed vast acreage to construct the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama; the Michoud Assembly Facility near New Orleans; the Mississippi Test Facility at Pearl River (now the John C. Stennis Space Center); the Launch Operations Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida (later the Kennedy Space Center); and the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. These sites helped create the so-called Sun Belt, where the size and wealth of a technocratic, professional white middle class came close to equality with the national average, exceeding it in some areas. Educated white newcomers to southern communities encountered revised patterns of racial division. “Well-guarded out-of-reach property values insured the perpetuation of a homogeneous society of middle- and upper-middle-class families,” Paul Gaston writes, “thus helping to insure a new form of segregation. As this separation was accelerating, class now joined or even supplanted race as the primary dividing line.”

The emerging paradigm comfortably fit the highly adaptable German scientist Wernher von Braun. Von Braun, MSFC director from 1960 to 1970, and the public face of NASA’s scientific expertise, was brought to the United States in 1945 to conduct rocket research for military purposes. His Nazi party membership and cold-blooded use of slave labor at the horrific Mittelbau Dora concentration camp was quietly forgotten, as was his role in the development of the V-2 rocket that wreaked havoc on London during World War II. Once in the United States, von Braun became a born-again Christian and a noted presence at MSFC prayer breakfasts. This religious conversion helped him fit in handily among southern evangelicals as well as in larger US aerospace and defense circles. While his rocket expertise is commonly known, his role as a progenitor of the new southern elite is not acknowledged.

Von Braun performed a third role as a purveyor of the imaginary that sustained NASA’s popularity. Humans had a divine mission, he declared. “Only man,” von Braun wrote, was burdened with being an image of God cast into the form of an animal… And only man has been bestowed with a soul which enables him to cope with the eternal… If man is Alpha and Omega, then it is profoundly important for religious reasons that he travel to other worlds, other galaxies; for it may be Man’s destiny to assure immortality, not only of his race but even of the Life spark itself… By the grace of God, we shall in this century successfully send man through space to the moon and to other planets on the first leg of his last and greatest journey.

There was a note of sadness in this apotheosis. Man’s greatest achievement would be to leave the planet rather than to embrace it. As a prophet of the future who had experimented with science fiction writing, von Braun portrayed the Space Age as one of “eternally renewable freedom” or, more darkly, as “escape.” His vision would color the imaginative thinking of scientists and infuse popular culture for years to come.

Historians have argued convincingly that acquiring information was a secondary priority for space funding. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon had all expressed some skepticism about space exploration’s scientific worth. Eisenhower complained of the cost. They yielded, however, to the realization that, in addition to the prestige competition with the Soviets, the space program would do important cultural work at home by holding out the possibility that age-old science fiction dreams might be fulfilled. Heroic astronauts would reaffirm the values of patriotism, self-sacrifice, bravery, and adventurous masculinity, traits threatened with disappearance during an age of presumed effeteness. Candidate John F. Kennedy had won the 1960 presidential election in part by impressing voters with his claim that America had gone soft and needed to regain the hardiness of its frontier heritage.

These cultural imperatives were powerful incentives for the rapid development of the Sun Belt and the aerospace industry. The ideology of progress embedded in Space Age development offered a carrot and a stick for integrationists and segregations alike. The carrot led proponents of integration to view the Space Age as a pathway to a racially just society, while the stick threatened to bar the way through inventive methods of segregation. Segregationists, enticed by the carrot of federal support, came to understand that government resources might be tied to discipline. Vice President Johnson linked progress in aerospace to “revolutions . . . in our industries, in our systems of education, in our hiring policies, in the realms of science, law, medicine, and journalism.” “Because the Space Age is here,” he informed participants at a Seattle conference, “we are recruiting the best talent regardless of race or religion, and, importantly, senseless patterns of discrimination in employment are being broken up.” Houston, where fortunes were quickly made in aerospace, provided an example. When the local utility company refused electricity to a naval base to protest the navy’s insistence on an anti-discrimination clause in its contract, LBJ informed the company that Houston could lose millions in federal contracts for the NASA satellite tracking station if bias persisted. The utility capitulated.

Excerpted from “The Newest South: Race and Space on the Dixie Frontier,” by Brenda Plummer in NASA and the Long Civil Rights Movement, edited by Brian C. Odom and Stephen P. Waring. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

(31)