How an onslaught of lies about COVID-19 overwhelmed our sense of what’s true

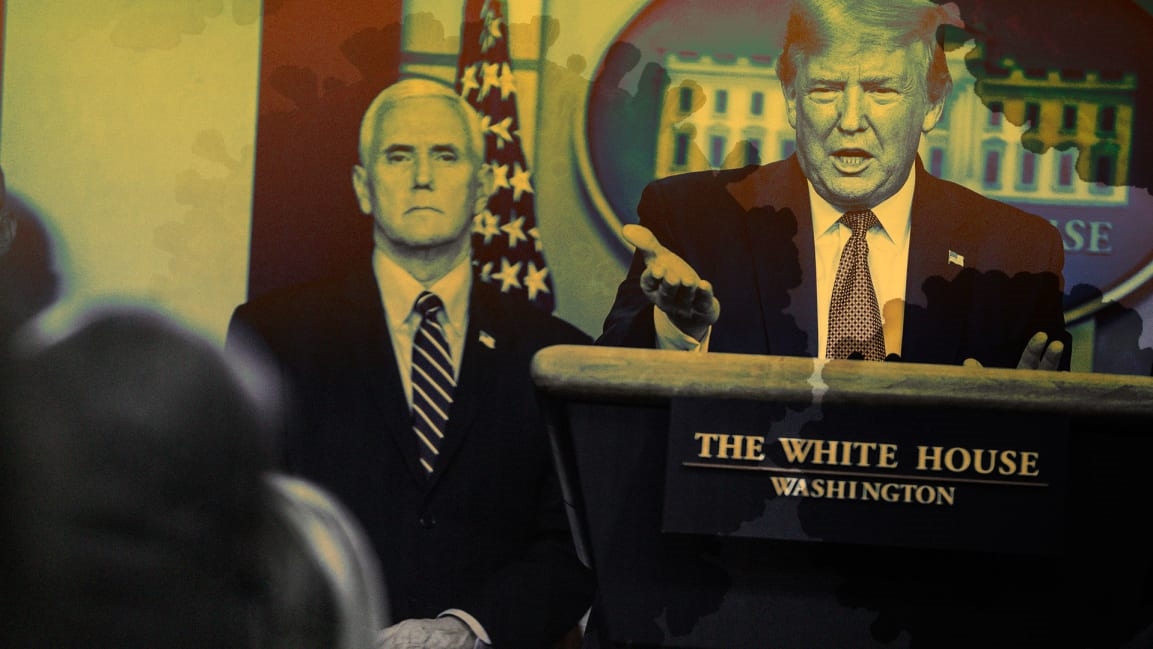

On the evening of March 25, President Trump tiredly ambled through his now nightly address, grabbing both sides of the podium authoritatively. “We’re also doing some very large testings throughout the country,” he said. “I told you (April 04, 2020) that, in South Korea—and this is not a knock in any way because I just spoke with President Moon; we had a very good conversation about numerous other things—but they’ve done a very good job on testing, but we now are doing more testing that anybody, by far.”

This boast, one meant to imbue the American public with confidence in federal efforts to quell the coronavirus, is not entirely true. As of today, the White House says the U.S. has conducted at least 894,000 tests, surpassing South Korea in sheer numbers. But South Korea has tested a far larger portion of its total population. It’s also unclear whether the U.S. has really tested the largest number of people. China has not published the number of tests it has administered nationally, though given the size of the population and its intensive efforts to quell the virus, it has likely tested a significant number of citizens.

But testing more than or better than any other country is beside the point. The U.S. should be enacting policies that effectively test American citizens. To some, arguing over test numbers can seem petty. On their own, Trump’s boasts may feel like harmless, minor offenses. But in great volume, these errors are pernicious because they become too numerous to fact-check, muddying the public’s overall sense of what is true.

In a recent Pew Research survey, 48% of Americans said they thought they’ve seen some COVID-19 news that seemed made up. Another 37% of Americans said they felt the news media has been exaggerating just how bad the impact of the coronavirus will be. Another poll from the Knight Foundation found that 74% of Americans were concerned about the spread of misinformation on the internet. The surveys convey that people are having a hard time knowing who to trust.

What I think people are really responding to is … a decline in trust in a variety of democratic institutions.”

John Sands, Knight Foundation

“What I think people are really responding to is a much longer trend: a decline in trust in a variety of democratic institutions,” says John Sands, the director of learning and impact at the Knight Foundation, referencing both his poll and the one from Pew.

One such institution may be the presidency. In daily press briefings, President Trump has repeatedly downplayed the potential impact of the coronavirus while Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a key member of the White House coronavirus task force, has offered a conflicting portrait. On March 24, President Trump laid out a case for reopening the economy in a matter of weeks rather than months. Just three days before, Dr. Fauci indicated self-isolation measures could last much longer.

“I cannot see that all of a sudden next week or two weeks from now it’s going to be over,” he said on NBC. “I don’t think there’s a chance of that—I think it’s going to be several weeks.” He reiterated that timeline over the weekend, telling CNN’s Jake Tapper that he doubts that anyone will be able to lift social distancing restrictions by Easter.

Dr. Anthony Fauci on when social distancing guidelines can be lifted: It’s going to depend a lot on “the availability of those rapid tests.”

“It’s going to be a matter of weeks … and if we need to push the date forward, we will push the date forward.” #CNNSOTU pic.twitter.com/mmL6dlUNve

— State of the Union (@CNNSotu) March 29, 2020

This is one of many discrepancies in the information shared by President Trump and Fauci, who has gently countered Trump’s optimistic narrative with a more realistic one. He’s become known as the administration’s truth teller for acknowledging the real situation on the ground: that we don’t have enough tests and we don’t know how long this all will last.

But when truth is presented at the same podium as misinformation, it creates an environment where the viewer is forced to discern for themselves what is true and what is false. Is the coronavirus really that deadly? Are young people immune to it or not? Could the impacts of self-isolation on the economy be worse for the American public than the disease itself? When will we be able to return to work in normal fashion?

The geography of misinformation

The president’s misrepresentations exist within a complex geography of false information online. Some of it is deliberately spread disinformation, for instance, Kremlin-sympathizing media seeding conspiracy theories that the U.S. created COVID-19 to upend the Chinese economy. Other reports are more opportunistic, such as people looking to make money off a coronavirus “cure.” Another set of opportunists are thought leaders without any medical background who attempt to model out the future, which has the effect of offering a flashlight in a fog. Still others are using misinformation to advance racist agendas, blaming the virus’s spread on certain groups—including the president, who for a time insisted on calling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus.”

Less noticed moment on Fox and Friends today >> Trump admitted to pushing disinformation on coronavirus when prodded by Kilmeade about China, Russia and Iran putting out disinformation:

“They do it, and we do it. Every country does it.” pic.twitter.com/gHFk4HZFlZ

— Ian Sams (@IanSams) March 30, 2020

Perhaps what is most concerning is the way false information has burst beyond the internet’s thin meniscus. Lies spout from the mouth of the president. Even mainstream news publications can have difficulty keeping track of the truth. Early on, in the first weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, The Washington Times, a conservative-leaning paper, published a conspiracy theory that the Wuhan Virology Institute had manufactured the coronavirus as a biological weapon (the story has since been taken down). In March, a member of China’s Foreign Ministry tweeted a counterconspiracy theory suggesting the U.S. was the real source of the illness.

“I think we have been drifting downward for years toward a growing and pernicious consensus that you can’t tell truth from falsity and there’s almost no point in trying to figure out whether there’s truth on a given subject,” says Paul Barrett, deputy director of New York University’s Stern School of Business and Human Rights, who has written extensively on misinformation in election cycles.

Who is the single greatest purveyor of domestically generated information? It’s no contest. It’s Trump.”

Paul Barrett, NYU

“Who is the single greatest purveyor of domestically generated disinformation? It’s no contest. It’s Trump,” Barrett says. He adds that the president gets assistance from Fox News, which amplifies his messaging. The president also parrots Fox News’s conservative-leaning reportage as well as the talking points of its commentators, creating a high-volume echo.

Fighting back against the lies

In the face of this overwhelming stream of falsity, social media companies have stepped up to combat some of the misinformation surrounding the coronavirus. Despite an everlasting commitment to free speech, both Facebook and Google have been working to take down false posts that could encourage people to harm themselves or others. They’ve also been promoting information from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in an effort to connect people with the facts.

Mainstream news outlets have also been fighting to dispel bad information that has gone viral. Pew notes that 70% of survey respondents feel the media has done very well to fairly well at reporting on the virus. It seems that Americans are also more savvy to coronavirus misinformation than other kinds. And yet, 29% of the people in Pew’s survey say they believe the virus was made in a lab, a conspiracy theory that Arkansas senator Tom Cotton has supported. As I’ve explained previously, COVID-19 occurs in nature, and diseases that spread uncontrollably do not make great biological weapons.

I can’t jump in front of the microphone and push him down.”

Anthony Fauci

While one can petition a social media site to have misinformation from spotty sources removed, information from Trump’s lips cannot. It cannot be flagged as false or misleading in real time. Fauci has been candid about this challenge: In an interview with Science magazine, he acknowledged that Trump sometimes gets information wrong in his speeches. Fauci says he does his best to make sure the White House knows when Trump gives false information to the American public. However, he says, he’s limited in his ability to actively correct that information in the moment.

“I can’t jump in front of the microphone and push him down,” Fauci said in the interview. “Okay, he said it. Let’s try and get it corrected for the next time.”

When siding with science is optional

President Trump continues to make recommendations that conflict with guidance proposed by medical experts. Last week, he said he’d like to restart business as usual by Easter, saying that such a plan could be executed regionally.

“You take a look at some states, they all have a little bit, but many of them have just a little bit and many of them have it under control,” President Trump said during an interview with Sean Hannity on Fox News. Some states will be happy to get on board with that agenda. However, the trajectory of the disease may force politicians to reconsider.

Whom do you trust for #coronavirus info:

Dems:

CDC 87%

Your governor 75%

National media 72%

Friends/family 72%

Religious leaders 44%

Trump 14%Republicans:

Trump 90%

CDC 84%

Friends/family 81%

Religious leaders 71%

You governor 65%

National media 13%-CBS/YouGov

— Ali Velshi (@AliVelshi) March 25, 2020

After conferring with Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx, an immunologist who is helping the White House coordinate a response to the coronavirus, President Trump said social distancing measures should stay in effect until April 30. Alabama governor Kay Ivey, who had previously resisted a shelter-in-place order, has decided to close nonessential businesses until April 17 but is only recommending that people stay home rather than enacting a statewide mandate (only Birmingham residents are required to stay home).

Efforts by Fauci and Birx show there is hope that Trump may ultimately listen to science and act accordingly. But regardless of whether Trump always sides with medical experts, he has given his audience the impression that he doesn’t have to. This division between Trump and scientists makes it seem as if reality is always up for discussion. When reality is not firm, it gives Trump an opportunity to mold it.

Though Trump is now extending social distancing guidelines, he has already said that hurting the economy could be more disastrous than the coronavirus itself—something people who place their trust in Trump will be unlikely to forget. For some, this back and forth may inspire a cavalier attitude towards social distancing or even a sense that the coronavirus is a hoax. Others will look for information elsewhere, whether that’s MSNBC, Fox News, or an alternative purveyor of information.

When people don’t know who to trust, then inevitably they will look to sources that jibe with their understanding of reality, regardless of their dedication to the scientific truth. If we all trust different sources, we will follow different guidelines. While that’s not ideal for a democratic society during normal times, it’s especially problematic in the midst of a pandemic. Fighting COVID-19 effectively requires everyone to be on the same page, adhering to the same rules. That’s how lockdowns can effectively reduce virus transmission.

The United States’s disjointed approach to curbing the virus’s spread is the reason some pundits believe that the U.S. is not “flattening the curve.” The growing number of cases certainly supports that notion. As of this writing, the U.S. is hurtling towards 200,000 cases of COVID-19. While that has immense implications for how many people ultimately succumb to COVID-19, there are still larger repercussions.

“[Trump] has ushered the society along towards the pole of just not knowing what to believe,” Barrett says, which has made us “skeptical of everything and susceptible to being manipulated to do anything.”

It’s not just that disinformation makes it more difficult to address the coronavirus in a coordinated way. It makes it difficult to run a democracy. When it has become too arduous to discern fact from fiction, we are in trouble.

(11)