How Jeff Daniels’ ‘Arachnophobia’ predicted disastrous U.S. COVID-19 response

Mayor Larry Vaughn, as portrayed by Murray Hamilton, is single-handedly responsible for keeping the beach in Amity open that fateful July 4th weekend, despite clear evidence of a still-imminent shark threat. As a result, one little boy was turned into a sushi platter on a floating raft. Mayor Vaughn has been a data point for the importance of local elections ever since, before recently becoming synonymous with the craven politicians whose main pandemic priority has been to keep the U.S. economy humming at all costs.

That moment when you realize that the White House response to the pandemic is literally the same as that put forth by the Mayor of Amity Island in Jaws.

— J. Michael Straczynski (@straczynski) September 20, 2020

The pandemic really lets everyone see where any given politician resides on the Mayor From JAWS Continuum

— Patrick Monahan (@pattymo) April 22, 2020

Miami Beach Mayor Calls Out Trump, FL Gov. DeSantis for Downplaying Pandemic Surge: ‘Everybody’s Become the Mayor in Jaws’ https://t.co/73Tog4L5Jx

— Mediaite (@Mediaite) July 7, 2020

Jaws is not the only movie of its ilk, however, to provide a cinematic precedent for America’s lackluster coronavirus response.

In the film, Arachnophobia, which makes good on the premise of ‘What if Jaws, but spiders?’, the bureaucratic valet to a predatory villain is not one man, like Mayor Vaughn, but rather an attitude prevalent throughout the fictional California town of Canaima.

Although Jaws-like fatalities abound in the film, it also offers an instructive look at how a town avoids descending into the full-blown disaster of COVID-era America.

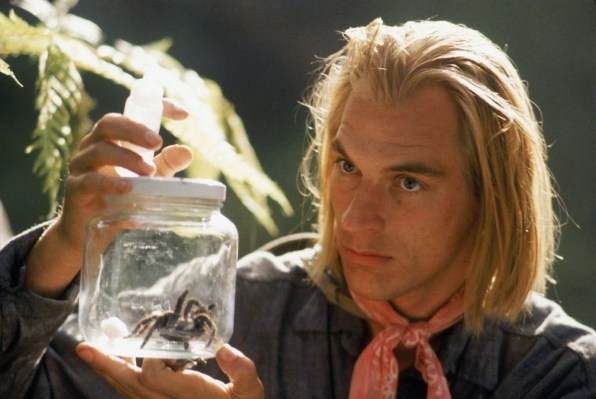

Arachnophobia, released 30 years ago this past July, stars Jeff Daniels as Ross Jennings, a San Francisco physician newly arrived in a small town in the California countryside. Also new in town is a mega-venomous spider, who stowed away in the coffin of a hometown photographer who was killed (by that spider) while visiting Venezuela. This Harry Hausen-like fuzzy creature then mates with a local breed of house spider, and its deadly offspring start to roam the area freely. Pretty soon, bodies are dropping left and right, and Dr. Jennings is the only person in town who suspects foul play.

Although politics are never explicitly mentioned in the film, we can sort of infer that Jennings is a typical San Francisco liberal. The filmmakers clearly want the audience on his side, but they’re not afraid to lean into some stereotypical hoity-toity behaviors. Jennings is every inch the coastal elitist. We see his smug glee over achieving the pinnacle of bougie dreams—a respectable wine cellar—and the look on a mover’s face as Jennings tells him how much the bottle he’s transporting is worth. Daniels’ character also refers to the town doctor whose patients he is set to inherit as an “old coot,” and laments having given up “culture” to move to Canaima and become the town doctor.

We’ve already been primed to roll our eyes at his condescending attitude by the time he starts bumping up against the local authority structure.

First and foremost is the old coot himself, Dr. Metcalf (Henry Jones), who has reversed course and decided not to retire, leaving Jennings without any immediate patients. No sooner does Jennings leave the doctor’s office, flabbergasted at this development, when the oafish Sheriff Parsons (Stuart Pankin) writes him a ticket for parking at an expired meter. Not before letting him know how unimpressed he is that the young doctor graduated from Yale, a fact Parsons picked up through the grapevine. (“It’s just a school,” he says while handing over the ticket.)

Luckily, one of Dr. Metcalf’s patients takes mercy on Jennings, walking by at that exact moment to snatch the ticket out of the sheriff’s hands and tear it up. This woman, the elderly Margaret Hollins (Mary Carver)—who knows a pointless power trip when she sees one—volunteers to become Jennings’ first patient. After he examines her in his office, determining her perfectly healthy, she even offers to throw him a party in her gorgeous country home, to introduce him to the town and possibly steer some of Metcalf’s patients his way.

Sadly, after the party, the new breed of spider follows Margaret back into her home, giving her a deadly bite. She is the first victim of the plague of spiders the town has no way of yet knowing has descended upon them.

If it were up to authorities like Dr. Metcalf and Sheriff Parsons, though, the town might not ever know.

Dr. Metcalf does a cursory investigation of the body on-site and immediately concludes that Margaret was done in by a heart attack.

Jennings doubts it. As he later notes, heart attack victims don’t typically bite their own tongues off.

Since he has recently examined Margaret and considers her to be under his care, he demands an autopsy be performed immediately. Dr. Metcalf strongly objects. “She wouldn’t want to be butchered,” he says, painting a common scientific practice as a barbaric ritual.

“You come from a big city where people don’t care about each other,” he adds. “I don’t expect you to understand.”

Metcalf is assisted here by the sheriff, who is more than happy to accept ‘heart attack’ as the official cause of death if his local doctor says so. He even glares at Jennings as he jots it down in the paperwork. The local authorities outmaneuver the big-city doctor here, without Margaret around to override them this time.

“Sorry I’m more interested in medicine than public relations,” Jennings snipes back about their lack of curiosity around finding out what caused Margaret’s death.

No autopsy is performed, and so the danger continues lurking around town with no commensurate alarm. Further deaths ensue, including a high school football player who dies, awesomely, when a spider in his helmet bites his head exactly one second before he is tackled by, like, nine guys.

Eventually, the stodgy Dr. Metcalf becomes a victim himself.

Jennings arrives first to the scene of his death, at home, where he is soon joined by the local coroner, a string tie-wearing hardass named Milt Briggs (James Handy.) By this point, the audience knows how authorities in this small town react to Jennings, and at first this one appears no different.

“You’re the hotshot who won’t accept anyone else’s diagnosis,” Briggs says when he realizes that the doctor he’s talking with is the one Metcalf told about him.

“I’ll accept it if I agree with it,” Jennings replies.

It is here that the path of the characters in this film—and that of many politicians in COVID-19 riddled America—diverge.

What happens next is like a form of intellectual pornography for survivors of the Trump era in general, and especially this current segment of it. Two people from opposing ideologies start off on the wrong foot, but put their differences aside and have a respectful conversation. They wade through empirical evidence together in hopes of solving a problem, rather than merely attempting to prove their rightness.

“I believe that’s a spider bite,” Jennings says of the gnarly conical welt on the deceased’s big toe.

“I’ll buy that,” the coroner responds. “But I rather doubt that’s what killed him. In 20 years, I’ve only seen one spider bite fatality and it was from a Black Widow.”

Briggs offers the alternate theory that Metcalf simply overexerted himself on the treadmill.

“You may be right,” Jennings concedes.

He wants a full autopsy, though, and because he and Briggs have been reasonable with each other in this examination, Briggs agrees with him, as long as Metcalf’s widow permits it.

The autopsy, of course, uncovers an as-yet identified toxic substance in the deceased’s bloodstream. It’s not conclusive, but it’s enough to point the pair in the right direction.

Pretty soon, the coroner, the doctor, some spider experts, and an exterminator (early Roseanne-era John Goodman) team up and save the town. Had they not, the citizens of Canaima would have been surely overrun by this extremely deadly new breed of spider and way more lives would have been lost.

In a hilarious nod to how the filmmakers themselves must identify as coastal elites, the film closes not with Jennings embracing small town life after this experience but instead getting the hell out of dodge and moving back to San Francisco.

That pivotal scene where the big city doctor and the small town coroner actually hear each other out demonstrates what was missing in how U.S. politicians approached the pandemic. Downplaying the threat for the sake of the economy is part of it—and it explains all the Jaws comparisons—but turning mask safety into the province of big city liberals who think they know everything is its own separate nightmare. It speaks to how the red state versus blue state divide has infected every facet of modern life, even things that should transcend it like, say, a pandemic.

Maybe the reason the characters in Arachnophobia could be reasonable enough to get on the same page and trust science is because Arachnophobia came out 30 years ago. Maybe the political climate at the time was less heated and our sources of information less divergent.

On the other hand, maybe the way people are now is more or less the way they’ve always been, and the reason Arachnophobia unfolds the way it does is because it’s a movie and not real life.

(35)