How Local Influences Drive Design In The Digital Age

It’s the regional innovations and variations that keep design relevant our hyper-connected digital age.

My wife is a hopeless flea market addict. I’ve been involved in this kind of scouting multiple times, exploring the same spot for years or rummaging through the oddest venues all around the world. “What are we looking for?” I used to ask at the beginning of my career as hunter’s assistant. The deal my wife was yearning for, and still is, was an authentic object, belonging to an authentic person who lived in an authentic place and behaved in authentic ways.

A few years ago I conducted a research study with my students on the relation between time, time zones, and social patterns. We decided to use selfies, taken at different times of day in different parts of the planet, as the main driver for our investigation. The discovery was quite disquieting. It didn’t matter if the images depicted a South American or an East European teenager; all the self-portraits looked terribly similar, and they all followed the pre-built path of digital self-portrait stereotypes, from foodies to feeties.

There’s a global hybrid aesthetic of the data world today. Should we just embrace it, or should we care more about what happens to authenticity? And is our digital reality even able to help preserve what we call authentic?

In 2006 Time’s cover was pointing at YOU as person of the year. YOU represented millions of anonymous contributors to the common cause of the net, who, rather than seeking Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame, are now playing the role of invisible ghost writers. It is true that digital tools provide vast possibilities but, at the same time, they expose us to the threat of aesthetic and cultural homogenization. If we look at the rise of desktop manufacturing, for example, and observe the products coming out from 3D printers, laser cutters, or CNC machines, we can observe a new and impersonal international style. The aesthetic of the fab lab is quite similar to the modernist aesthetic of the machine, where design is a direct representation of technology and there is very little space for local identity.

You cannot really say where a website has been designed or where a code has been written or where a piece of plastic has been printed; you can eventually only recognize which kind of tool has been used to shape them. Objects that originate from analog production, on the contrary, are more often connected to local resources and specific cultural nuances. The textile industry was historically based on water-powered mills and located in regions with streams and rivers; paper umbrellas were created to protect nobility from sunlight in response to a social demand for pale skin characteristic of specific cultures.

The emotional relationship we develop with our belongings is important, but how can we deal with authenticity? I’m interested in bottom up phenomenon, where new design approaches foster genuine localism and product de-globalization. Cultural hacking is an important part of the process for bringing authenticity back to products. Middle-Eastern-hacked Ikea furniture or the Icelandic Lego made of fish bones are straightforward examples of physical transformation from global to local, from anonymous to authentic artifacts.

In these examples, however, the transition happens from object to object, and physicality has a certain advantage in matters of authenticity. To identify attempts at localism in digital form, we should look at physical representations of the digital, where virtual data are translated into physical outcomes, and physical perceptions of the digital, where the transition from data to data is able to create a tangible interpretation of local realities.

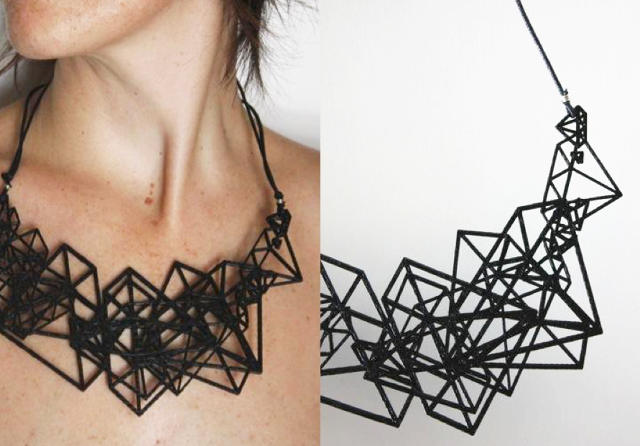

One of my own attempts at physical representation, trying to address this analog/digital-global/local glitch, is a 3D-printed necklace generated by a string of code. One of the parameters for defining the necklace’s shape was the machine’s geo-location and the correspondent country’s GDP. If the system were processing and 3D printing a necklace in Qatar, the place I was living at that time and one of the richest countries in the world, the location- and GDP-based code would produce a chain of many, large diamonds shapes; differently, in the Republic of Congo, at the other extreme of the wealth ladder, the digital product would be only one tiny diamond shape.

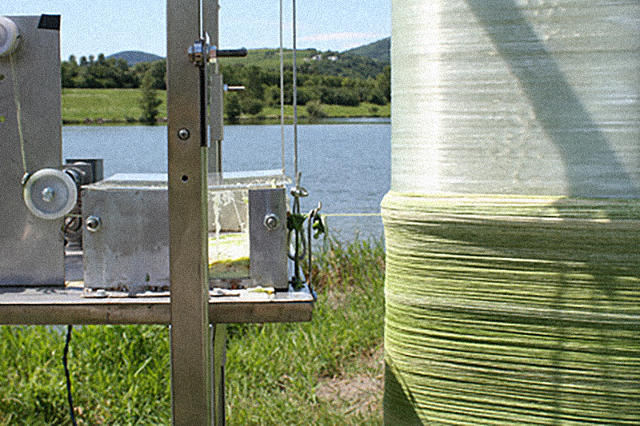

In “The Idea of a Tree” by Mischertraxler studio we can recognize a related experiment with physical representation in which the source is not socio-economic as in my necklace project, but rather local environmental conditions. In this case a machine uses sunlight data to determine the shape and colors of a bench that becomes a physical representation of the weather in that specific place at that specific time. “Windmaker,” a project developed within Yale’s graphic design department, is based on the same idea, but the localization process happens through physical. Windmaker uses postal codes to visual the local current wind conditions in any website. No object is involved here, but the virtual reproduction of a natural state is creates a strong and poetic link between what is perceived on the computer screens and what is seen through the windows.

CLUE, or “Culturally Localized User Experience,” is how Huatong Sun in her bookCross-Cultural Technology Design defines the translation from globally distributed technology into local habits and cultural heritage. She analyzes the case of mobile phone texting and describes how people all around the world manipulate technology to better fit their specific needs. In Arab countries, for instance, an improvised alphabet named Arabizi, consisting of the phonetic pairing of roman symbols and numbers with the Arab alphabet, is used by youth to chat on their phone’s Latin keypads. Can we start thinking of Culturally Localized Digital Objects?

In the current world of ubiquitous Apple style, a push towards localism and cultural customization seems needed to escape the present market’s blandness.

In the Third Industrial Revolution, digital manufacturing and self-production allow objects to be designed and produced anywhere at anytime. If we agree that the future of product design should be democratized and localized, we should focus on authenticity—based on locally determined physical representations and physical perceptions of the digital—as a key factor in the development of valid design solutions.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(53)