How NASA keeps its astronauts safe and sane in space

Astronauts endure one of the most dangerous, high stakes, high stress professions on (or off) the planet — a job matched in isolation, confinement and extremity perhaps only by arctic field scientists and ballistic missile submarine crews. Of course, the latter two rarely have to deal with radiation exposure, gravity changes, or the prospect of being sucked out an airlock.

As such, NASA has spent decades working to ensure that, when it sends crews beyond the atmosphere, they’ll possess the talent and training required to do their duties and return safely. As we look towards Mars — and its two-plus year round trip — NASA faces an unprecedented challenge in doing so.

Even on relatively short stints aboard the ISS, astronauts face a number of challenges and contributing factors that can wear on them physically and emotionally. Those include potential personality and cultural conflicts or communication issues with foreign crewmates, the monotony and boredom of performing daily maintenance on the station, physiological changes due to microgravity and isolation, worries of radiation exposure and disruptions to their circadian rhythms. Astronauts on the ISS are essentially stuck in a little bubble of habitable atmosphere with only five other people for six months at a time or more. That’s enough to make all but the most psychologically sturdy go a bit stir crazy.

Per NASA’s research, US astronauts suffered 1,800 in-flight medical events over the course of 89 shuttle missions between 1981 and 1998. Fewer than 2 percent of those were due to behavioral health issues and among those, the most common complaint was “anxiety and annoyance.” Conversely, Space Adaptation Syndrome — wherein astronauts suffer from motion sickness, headaches, and facial stiffness until they grow accustomed to life in microgravity — accounted for 40 percent of medical issues over the same span.

That’s not to say astronauts don’t go a little crazy from time to time. The Soyuz 21 mission in 1976 had to be abandoned when the cosmonaut crew all noticed a strong odor in the capsule. The source of the smell was never found and the entire incident was chalked up to a shared, stress-induced delusion among the crew. In 1989, shuttle commander David Walker, recently returned from his first mission and in the midst of a bitter divorce, piloted a T-38 jet within 100 feet of a Pan American commercial flight. While NASA never officially cited post-mission stress as a contributing factor to the near disaster, the agency did remove Walker from command and grounded him from missions until 1992.

More recently, in 2007 astronaut Lisa Nowak drove non-stop 900 miles across the country, armed with an adult diaper, bb gun, mallet and knife to confront a romantic rival at the Orlando airport. After failing to pepper spray her rival, Nowak was arrested and charged with attempted murder. Her legal team pursued an insanity defense following a diagnosis that Nowak suffered from a brief psychotic disorder and major depression after returning from her recent Discovery mission.

“Anecdotal and empirical evidence indicate that the likelihood of an adverse cognitive or behavioral condition or psychiatric disorder occurring greatly increases with the length of a mission,” NASA’s Human Research Program found during a subsequent study on astronaut psychological health. “Further, while cognitive, behavioral, or psychiatric conditions might not immediately and directly threaten mission success, such conditions can, and do, adversely impact individual and crew health, welfare, and performance.”

NASA’s first line of defense against this happening is its brutal astronaut selection process. Many candidates come from high-pressure fields such as fighter pilots and physicians, inherently dangerous, high-stakes professions where a wrong move can prove fatal. The ability to quash fear and anxiety to overcome a challenge is of paramount importance. Astronauts “already know [they] can meet stressful challenges,” NASA senior operational psychologist Dr. Jim Picano told Astronaut in January, “and [they] believe [they] can overcome these things.”

A rigorous training regimen helps iron out any remaining doubts the candidates may have. “The training that astronauts receive shapes their confidence in the procedures and equipment they have, to deal with spaceflight commands as well as emergencies,” he continued. “Rehearsing these over and over again…brings a sense of preparation that allows them to believe they can influence and change their circumstances for the better.”

Of course, confidence can only get one so far in the selection process. Out of the 18,000-odd applicants, only a pool of 60 or so will eventually be eligible to go to space. NASA rates each of these applicants on nine separate “suitability proficiencies“

-

The ability to perform under stressful conditions

-

Group living skills

-

Teamwork skills

-

Self-regulation of emotions and mood

-

Motivation

-

Judgement and decision making

-

Conscientiousness

-

Communication skills

-

Leadership skills

And that’s just the start. Candidates are subjected to hours of psychiatric screening during the selection process to ensure that they have “the right stuff” for a given mission. Once selected, astronauts must then go through multiple additional batteries of psychological evaluation and support during the run up to launch, while on mission, and after they return. While aboard the ISS, crews participate in psychological conferences with ground-based medical staff, for example.

Additionally, NASA takes great pains to keep astronauts aboard the ISS in contact with their friends, families, and the public to help counter the enormous psychological stresses they experience. NASA provides its ISS astronauts access to social media accounts, satellite phones and video conferences for communicating with family, media downloads for keeping up with the latest TV seasons, and regular care packages from Earth. Astronauts are also encouraged to take up hobbies while aboard the space station; be it photography, reading or in Commander Chris Hadfield’s case, recording a guitar album in microgravity.

NASA is also looking into less invasive ways of monitoring its astronauts’ mental health while in space. “Researchers funded by NASA have been experimenting with visual recognition technology,” Dr. Lawrence Palinkas, professor of Social Policy and Health at the University of Southern California, told Engadget. The same sort of technology that law enforcement agencies are using to track and identify people could eventually be used to subtly keep tabs on a crewmate’s psychological state. “If aberrations or abnormalities are detected, a psychologist is armed with more detailed information on how to respond adequately,” he said.

Still, Mars is 35 million miles from the Earth, even at their closest orbital points. Getting there and back will take a minimum of two and a half years. “Mars is a long way away, and the extreme distance has psychological ramifications,” Dr. Nick Kanas, emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, told the American Psychological Association in 2018. “It will be hard to have the kind of social novelty we crave.” Given the scope of the mission, multiple nations’ respective space agencies will be involved and likely sending astronauts of their own.

Dr. Phyllis Johnson, associate professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia, has recently performed research into the effects that these sorts of dangerous and remote jobs have on family members left behind. “We’re looking at how [astronauts] create, or do they create, a shared space culture,” she told Engadget. “Or are they going to be separate entities of ‘I’m my national culture. So I’m an American there first, and I’m a Canadian, and I’m a German, or I’m from a particular space agency.'”

“Are they developing something that encompasses all of it,” she continued, “and do they see it as recreating some traditions — customs that we’re doing as a team — that are carried forward by other groups.”

That community will be vital given that the further they travel from Earth, the longer the communications lag grows. By the time the time they make it to Mars, signals from Earth will need a full 20 minutes to get there. Combined with an equally long trip back and the time needed to compose a reply, astronauts will be looking at a 40 minute lag at the very least. That will make telephone-style conversations impossible.

“Undoubtedly protocols that will have to be established for how that form of communication takes place,” Palinkas said, “and how questions and answers are bundled together to minimize disruption to the normal flow of conversation.”

NASA isn’t planning on sending a crew to the Red Planet for nearly another decade, not when there’s so much Moon to explore and potentially exploit. This should give the space agency sufficient time to further mature the technologies and flight systems needed to keep its astronauts alive, and more importantly, thriving, during their perilous journey.

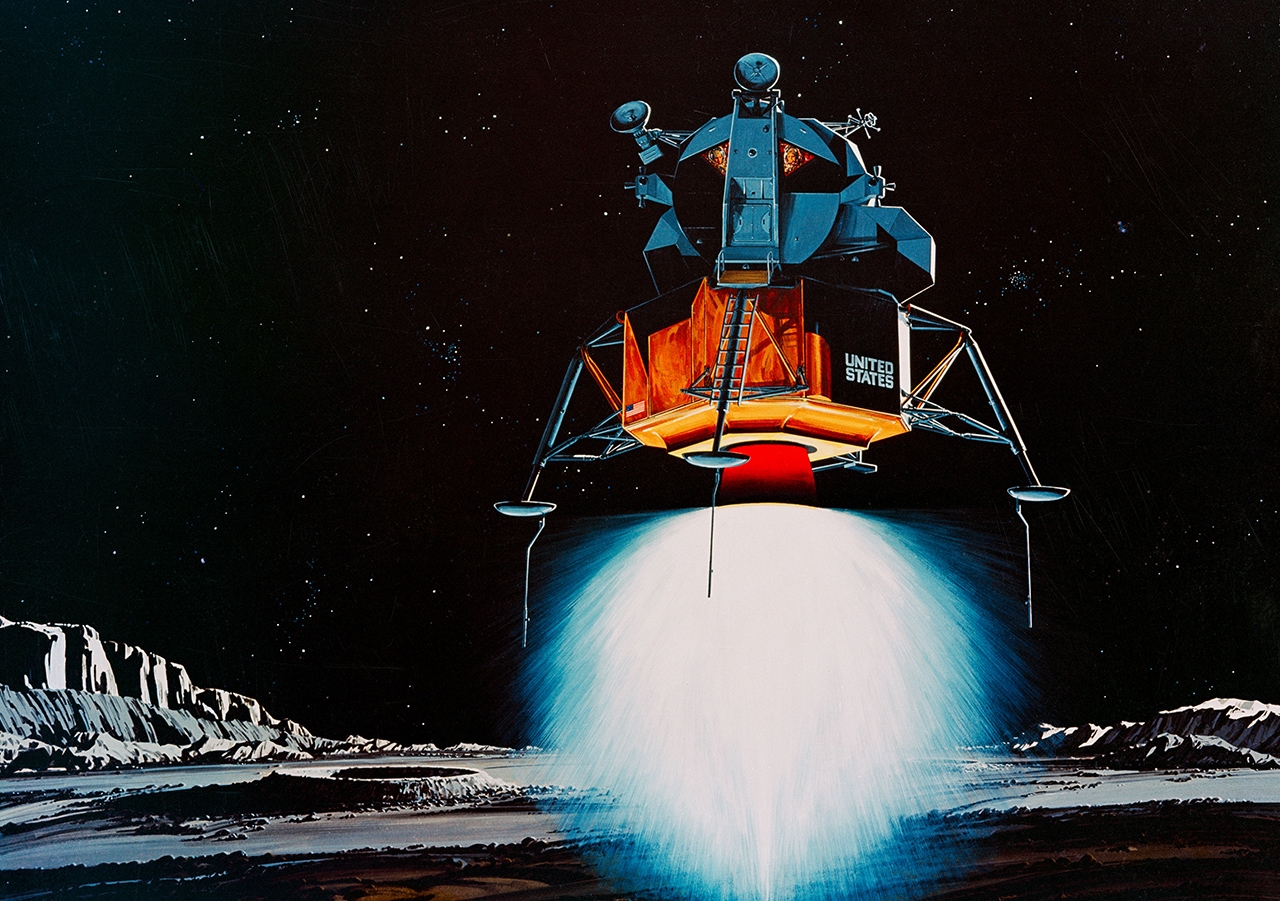

Apollo 11 anniversary

(67)