How Tech Giants Helped After The Bastille Day Attack (And A French App Didn’t)

When terror attacks, natural disasters, or big accidents occur, people in the danger zone need information about what to do and where to go. Family and friends of those affected seek out information about the safety of loved ones. And the public needs some way to discern fact from rumor as emergencies unfold.

Silicon Valley giants like Twitter, Facebook, and Google occasionally launch or update initiatives designed to help during emergencies. Governments increasingly embrace mobile technology to coordinate public safety.

But how effective are these products and services when disaster actually strikes?

Last week’s Bastille Day truck attack in Nice, France, killed at least 84 people. The driver of the truck, identified as 31-year-old Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhle, was shot and killed by police.

The attack was sudden, unexpected, and horrific. As such, the event also serves as a much-needed reality check on the current state of public emergency alert systems.

I happen to be living in the South of France at the moment, in Aix-en-Provence, which is 100 miles or so from where the Nice attack took place. The randomness of such events hit home when I realized that our original travel plans would have put us in Nice at the time of the attack. By chance we discovered that the AirBnB we wanted to rent in Nice overlooking the famous Cours Saleya market (just one block from the Promenade des Anglais where the attack occurred) was steeply discounted in October. So we postponed our stay in Nice.

My son had made some local friends here and was enjoying a Bastille Day house party when the attacks occurred. Revelers were dancing and drinking and having fun when suddenly the music stopped and everyone began using their phones in a panic. One girl called her parents, who she knew were having dinner in Nice at the time. Others called or texted family and friends to see if they were okay. Everyone else turned to Twitter or other mobile apps or sites to get news updates.

So how did the alert and emergency information systems perform? I looked at four companies: Twitter, Facebook, Google, and a Paris-based company called Deveryware, which maintains the national alert app for the French government. Here’s what I found.

Twitter: Connecting People, Quashing Rumors

Millions of people first heard news of the attack on Twitter. English-speaking users immediately started gravitating around the #PrayForNice hashtag and French speakers favored #JeSuisNice.

An ad hoc, user-driven effort to provide news and to connect affected people emerged. Twitter accounts called @nicefindpeople, @nice6recherches, and @Avis2recherche began curating tweets from family and friends who lost contact with people at the site of the attack. Some users are seeking information about loved ones using the hashtags #Nice06 and #RechercheNice. The hashtag #PortesOuvertesNice served to connect people offering or needing a place to sleep.

Crises are often attended by false rumors on Twitter, and the Bastille Day attack was no different. A man named Veerender Jubbal, for example, was falsely accused on Twitter as the driver of the truck. Sound familiar? In fact, Jubbal was also the subject of a false rumor that he was involved in the Paris terrorist attacks last year. Jubbal, who is a Canadian Sikh, freelance journalist, and Gamergate critic was smeared with Photoshopped images and false accusations by pro-Gamergate trolls. A Twitter account recirculated the same doctored photos with an updated false accusation. The offending account was deleted quickly by Twitter.

ISIS supporting, pro-attack tweets emerged quickly from more than 50 accounts in the immediate aftermath of the Bastille Day attack. Critics applauded Twitter’s fast action in removing the offending tweets and accounts. The Counter Extremism Project said in a statement that “Twitter moved with swiftness we have not seen before to erase pro-attack tweets within minutes. It was the first time Twitter has reacted so efficiently.”

Coincidentally, a truck caught fire near the base of the Eiffel Tower within a few hours of the attack in Nice, engulfing the tower in smoke. Rumors spread on Twitter about a possible, coordinated Paris attack as well. Eventually, the facts emerged on Twitter, but even then some were incredulous. One user tweeted: “We’re supposed to believe there just happened to be an accidental fire at the Eiffel Tower at the same time as #Nice. Yeah right.” The results of my searches for the false-rumor tweets returned mostly explanations and warnings that the rumors were false.

Twitter gets high marks for quelling these rumors, suppressing hateful content, and generally providing clarity in the chaos.

Facebook: Safety Check At Work

Facebook immediately activated its Safety Check feature in the wake of the Bastille Day attack.

Facebook uses both the city you list on your profile and also the last-known check-in to selectively offer the question: “Are you in the affected area?” By clicking “Yes, let my friends know,” Facebook will inform contacts on the social network that you’re okay.

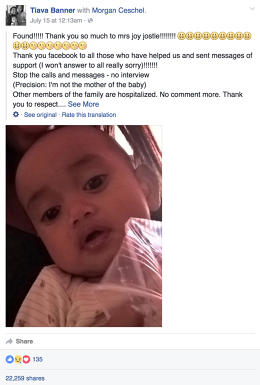

Facebook also facilitated the recovery of a baby lost in the chaos. A woman named Tiava Banner posted on Facebook with the somewhat cryptic post: “we lost BB 8 months. Nice friends if you’ve seen him if you were there if you have collected please contact me!!!!!”

The post quickly went viral, and within hours the woman posted another update saying that the baby had been recovered. The post also said that she was not the mother and that the baby’s family was still in the hospital. (The French AFP news agency reported that another woman had found the baby alone in the chaos after the attack and took him home with her.)

Facebook did make an error the company regretted. The Facebook Newswire page picked up a graphic video of the attack originally uploaded to Instagram. Facebook editors removed the video after it was criticized as insensitive to victims and their families.

In general, however, Facebook’s Safety Check feature provided an organized way for users to check in on family and friends, and Facebook’s popularity and ubiquity enabled real and fast communication between not only loved ones but also strangers.

Google: Eclipsed By Twitter And Facebook

Google takes a more ad hoc, crisis-by-crisis approach to helping users during emergencies.

Google rolled out more than four years ago a Crisis Map and Public Alerts system, which can show up on various Google properties, including Google Now. But the services are focused on natural disasters, not attacks like the Bastille Day event.

Google used to create Crisis Response pages to help coordinate and inform victims of natural disasters, but it seems to have stopped doing this about three years ago.

Google’s Crisis Response Google+ page hasn’t been updated in more than seven months.

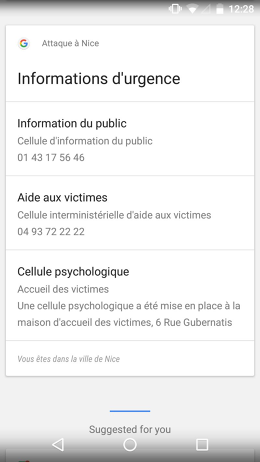

Google told me they “work with government and official authorities to provide information that may be most useful” during emergencies, and in Nice they did this in part through location-specific Google Now cards. One card offered the phone number for public information about the crisis, and another to help victims.

Google highlighted the ability of Google Maps to show road closures in the wake of the attack, and they put a black ribbon on the Google France home page for three days.

The company also removed any long-distance fees for calls to France from anywhere in the world via Google phone services: Hangouts, Google Voice, and Project Fi.

Google may have been very fast with Google Now and Google Maps-related information, but in general Google’s efforts were eclipsed during the Bastille Day attack crisis by Twitter and Facebook.

Deveryware: What Happened?

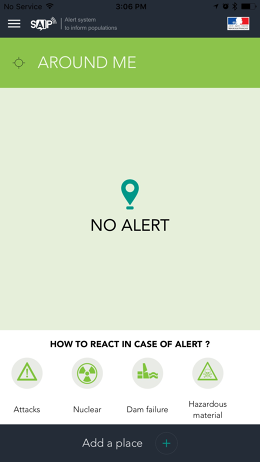

French media reports say that a government alert app, which is supposed to send out warnings within 15 minutes of any sudden crisis, took more than three hours for the message “take cover” to arrive. The month-old app, which is called SAIP (Système d’Alerte et d’Information des Populations) clearly failed to be useful.

Although SAIP is meant for use in any emergency, terrorism is driving its adoption. (France has been targeted by seven terror-related incidents in the past 18 months.)

The app is well designed and supports both French and English. It tells you “no alert” most of the time, based on your current location. Best of all, you can specify up to eight French locations to be alerted about.

The failure reportedly resulted from a yet-unspecified technical problem, which could be related to mobile network congestion during the crisis. Paris-based Deveryware, which developed the app and sends the alerts, has not issued a public statement and did not immediately respond to my request for comment. Deveryware representatives were summoned to the Interior Ministry to explain the failure, according to a report in Le Figaro.

The short-term solution to the SAIP failure: A French secretary of state, Axelle Lemaire, urged French citizens to use Facebook’s “Safety Check” instead.

That turns out to have been very good advice, to which one could have added: Check Twitter, as well.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(10)