How the ISS National Lab went commercial

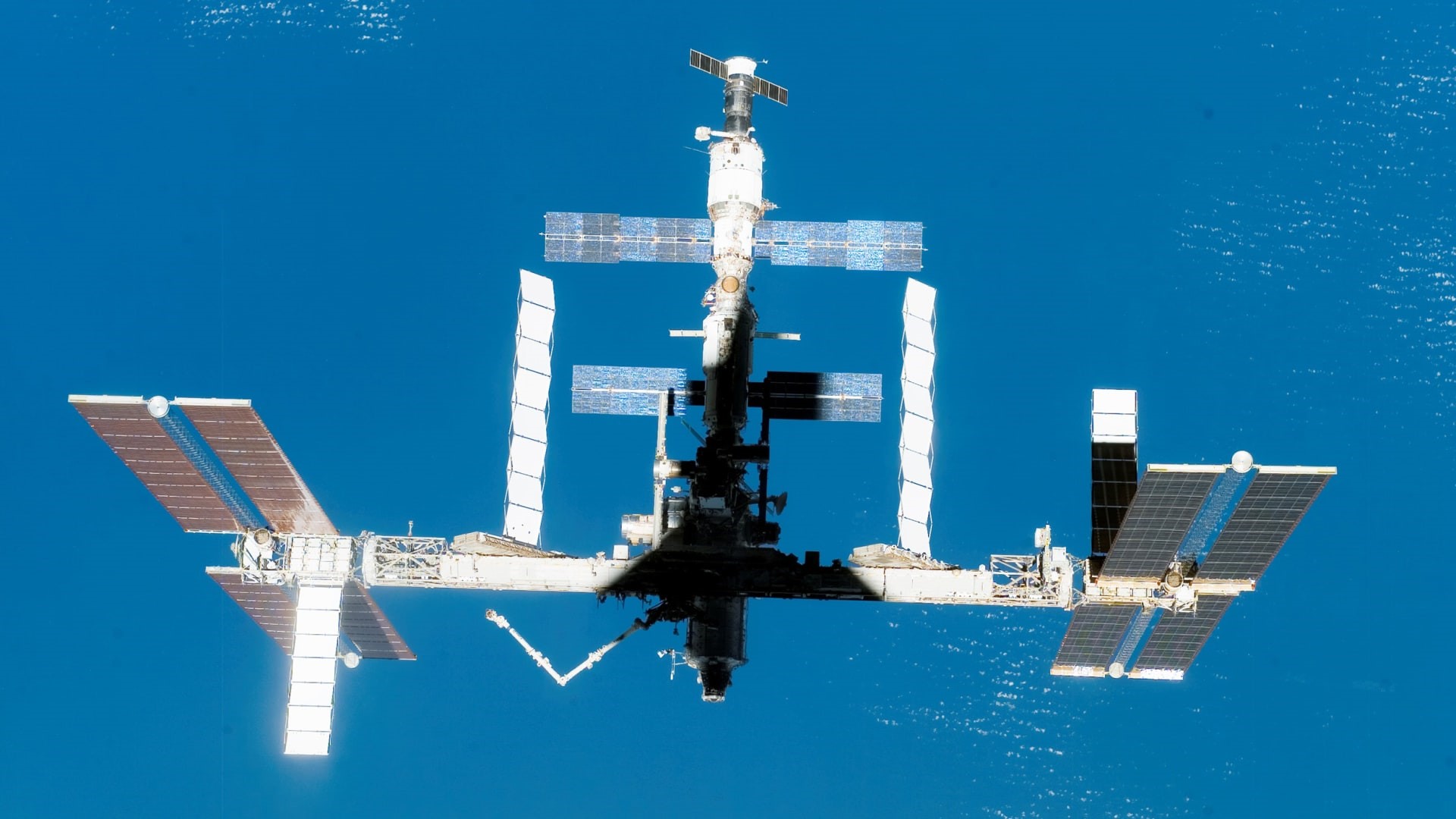

How the ISS National Lab went commercial

The lab’s chief scientist sat down to discuss what’s planned for the organization after the ISS decommissioning.

BY Rachael Zisk

The U.S.’s highest scientific laboratory is changing with the times.

Michael Roberts is the chief scientific officer of the International Space Station National Laboratory, a government-funded organization that helps connect non-NASA scientists and companies with opportunities to perform research aboard the station. Roberts sat down to discuss the lab’s priorities, how its relationship with the commercial space industry has developed, what’s planned for the lab after ISS decommissioning, and the anticipated rise of commercial outposts to take its place in low Earth orbit.

“We’re seeking to optimize access to space because it is a precious resource,” Roberts said. “The cost of getting to low Earth orbit has fallen significantly over the past several years, largely through the initiative of NASA engaging with the commercial sector to build new capabilities, and then the response of industry.”

A national lab in space

The ISS National Laboratory was established through an act of Congress in 2005 to help bring nongovernmental researchers and companies in on performing research in space. Like any national lab, this one is meant to fund research that serves the national interest—including scientific research that could have a public or business impact, or through testing products to move them toward commercial viability.

“The purpose of the National Lab is to grow by engaging with business and hopefully moving towards a business model,” Roberts said. “Being able to work with industry at the speed with which the industry wants to move, not the speed with which a large federal bureaucracy wants to move.”

For most of the National Lab’s history, the process for approving experiments could be straightforward. Researchers or businesses would submit proposals to the lab, which would review them and decide which received funding and support to perform research on the station.

Enter industry

Over the past decade or so, commercial facilities have opened their doors on the ISS. Redwire Space, for example, owns and operates an additive manufacturing facility on the ISS, and Aegis Aerospace owns and operates an external testing lab attached to the station.

These companies have full control over what research goes in.

When working with commercial partners, the lab no longer chooses exactly which experiments or demonstrations get approved to fly to the station. Instead, operators of the individual facilities aboard the ISS are trusted to decide who they work with and what needs to get done, and the lab takes more of a reviewer role at the end of the process. Ideally, these companies know best what is going to make the best use of their technology.

“We don’t put our thumb on the scale a whole lot and say, ‘Hey, we’re only looking at improving the quality of chicken eggs for the next five years,’ but we will say, ‘Hey, should we fly more chickens? Does that make [economic] sense?’” Roberts said.

Passing the torch

The ISS is reaching the end of its life. It’s old, leaky, and rumor has it that it doesn’t smell great after more than 24 years of hosting astronauts without cracking a window.

New digs are in order. A number of space companies have stepped up to build commercially funded space stations, both in partnership with NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations program and independently. The ISS National Lab, with less than a decade to go before the transition will have to be made, is preparing for the change.

“Those service providers who operate and maintain those facilities have the ability to go out and sell their services to others, to bring them on board,” Roberts said. “That’s going to be the important transition we see as we move off-station on to commercial platforms in the future. It’s going to be more of a commercially operated venture.”

Roberts said that ISS National Lab leadership is also in frequent communication with leadership of the CLD program and the potential commercial space station operators to figure out how government-funded research will fit into their operations.

“We’re valuable to that conversation—I would say critical to that conversation—because we’re the interface between a lot of these commercial companies that provide the services and the hardware on the International Space Station,” Roberts said. “Many of them, and more that are being created every day, will be critical to the facilities and capabilities of these commercial platforms in the future.”

As for the Lab . . .

Without the ISS, there’s no ISS National Lab. There is, though, a plan for transition. In a 2022 update to its official transition plan, NASA outlined the need for a National Lab in low Earth orbit, which, if enacted by Congress, would support continued government-funded research initiatives aboard CLDs.

This story originally appeared on Payload and is republished here with permission.

Recognize your company’s culture of innovation by applying to this year’s Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the final deadline, April 5.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

(8)