How This Technology Is Making Doctors Hate Their Jobs

Matthew Walvick is a doctor. But until recently, when he left a large hospital to work at a startup, he felt like his day was utterly consumed with data entry.

Walvick, a former internal medicine physician at John Muir Health, recalls spending endless hours checking boxes and filling out charts on the hospital’s electronic medical record system. As soon as he returned home after an exhaustive day, he’d hit refresh and be faced with yet more computer work—much to the dismay of his family.

It wasn’t all that long ago that doctors’ records consisted of scrawling handwritten notes in a binder. The transition from paper-based systems to digital ones kicked off in 2009, under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009, which incentivized providers to adopt electronic medical records. That law took effect in January of 2011.

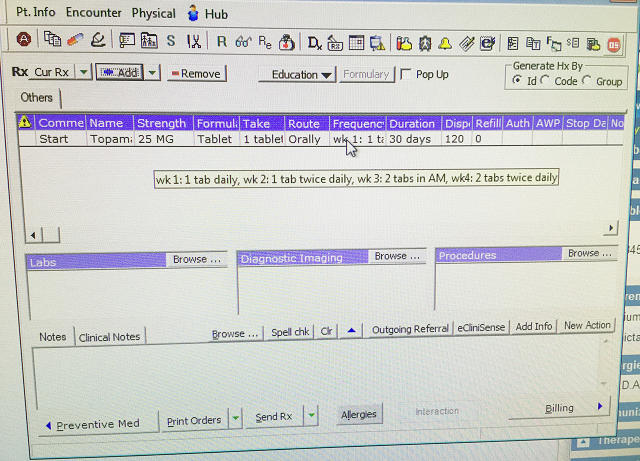

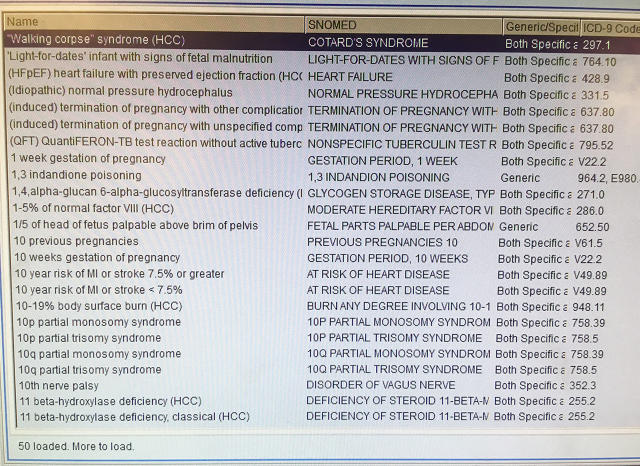

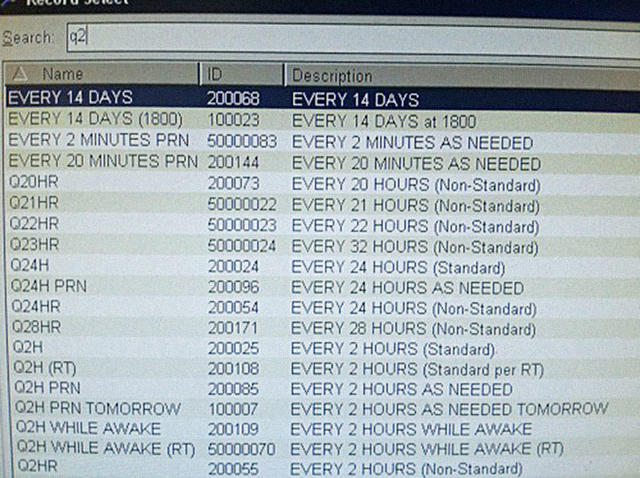

This technology was supposed to reduce inefficiencies, make doctors’ lives easier, and improve patient outcomes. The only problem? Many hospitals spent millions (and sometimes, billions) on systems that weren’t designed to help their providers treat patients. “Frankly, the main incentive is to document exhaustively so you cover your ass and get paid,” says Jay Parkinson, a New York-based pediatrician and the founder of health-tech startup Sherpaa.

Indeed, physicians tell Fast Company that these systems are about a combination of meeting regulatory requirements, maximizing billing, and avoiding liability. “I would describe the practice of medicine today as a festival of measurements that have little to do with patient care,” adds Jordan Shlain, a Bay Area-based primary care physician with Private Medical Services.

Even in cases where the system is ostensibly set up to help doctors, it falls short. Many physicians are now facing an increasing deluge of alerts, including pop-ups about vitally important things as well as utterly meaningless ones. “Many of us are now becoming immune to these alerts,” says Nate Gross, a doctor who cofounded both Rock Health and Doximity. “It’s a user-experience flaw: These systems were not designed to follow how doctors actually think.”

Arguably, the biggest problem is that it’s a nightmare for doctors to share vital patient information from one hospital to another. These systems were intended to be interoperable, meaning it would be easy for a doctor to obtain a record from another facility. That didn’t happen, in part because it it doesn’t help the bottom line of the biggest medical record vendors or the hospitals to make it easy for patients to change doctors.

“It can sometimes take weeks, or months,” to get a copy of the patient’s record via fax machine from another hospital or clinic and upload it to their medical record, says Walvick. And that, according to Consumers Union staff attorney Dana Mendelsohn, increases the chances of doctors ordering duplicate tests and the likelihood of medical records.

This compilation of factors has resulted in doctors burning out at unprecedented rates and spending less quality time with patients (the average is now about eight minutes and 12% of their time), according to a recent study, down from 20% of their time in the late 1980s.) This group is 15 times more likely to burn out than professionals in any other line of work. And much of the research on the topic concludes that “documentation overload” is a key factor. A Medscape study from 2015 reported that just shy of half of physicians were experiencing burnout. And three of the top four reasons were related to the electronic medical record.

Some physicians are no longer optimistic about potential solutions, but others say that important changes are finally underway.

“Yes, there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” says Shlain. “It’s a train of frustrated physicians who are getting involved and starting to take action.” Many doctors are already starting or joining new companies that aim to build user-friendly applications on top of the electronic medical record, which fit neatly into the clinicians’ workflow.

Moreover, some hospitals are investing in making much-needed improvements to their medical record systems. John Mattison, a doctor and the chief medical information officer at Kaiser Permanente, Southern California, says his team is working to refine the medical record to reduce the number of clicks and other inefficiencies. As he explains, these systems still do have the potential to improve patient care if they can deliver the right information at the right time, like nudging a doctor to check in with a sick patient.

Solving these problems won’t be easy. But rather than throw out these systems altogether, medical groups are putting together practical plans to address these gaping problems by 2020. And that includes reducing the data-entry burden for doctors, so they can shift their focus to patient care.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(24)