Huge Swaths Of America’s Communities Are Economically Stagnant: How Can We Make Them Grow?

After the dust from the 2008 recession settled, the consensus around the U.S. economy has: We’re doing fine. From 2011 onward, national-level jobs reports have shown a fairly steady uptick in employment and new business formation. From an unemployment rate of around 10% in 2010, we’ve dropped down to just 4.4%.

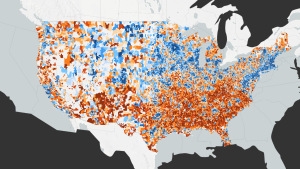

This linear growth is misleading. Look to “tech hubs” like San Francisco and Austin, and sure, you’ll see booming growth; in America’s most prosperous communities, new businesses have been added at a rate of 12.6%, and employment has ballooned by nearly 25%.

But in the 5,225 zip codes across the U.S. that, in a new report, the tech-billionaire backed, pro-entrepreneurial nonprofit Economic Innovation Group has labeled “distressed communities,” you’ll see a very different picture. In Midwestern cities gutted by the decline of manufacturing, like Cleveland, and across much of the deep South, employment has dropped by 6%, and instead of new businesses being established to create more jobs, they’ve been disappearing at a rate of 6.3%. These are “the places that have fallen through the cracks of the U.S. economy,” according to the report. In these communities, the recession essentially never ended, and the gulf between them and the top economic engines of the country is only growing wider.

This is a familiar narrative: Many of the prominent divides in the report–between urban and rural, between North and South–have been held up as the cause of the Trump presidency. Last year’s Distressed Communities Index, released in February of 2016, outlined similar trends. But this year, says John Lettieri, EIG co-founder and senior director for policy and strategy, the research team wanted to branch out from examining the divide, and get more into the conditions it produces. “The question that we’re trying to answer is two-pronged,” Lettieri says. “What is the nature of the geographic divide in terms of how growth is being distributed across communities? And for individuals, what are the implications of those divides?”

In terms of health, the impact of community-level distress is disturbing. “Often, research looks at individual health and individual well-being,” Lettieri says. “We wanted to take that up to the community level and understand how places impact people in terms of everything from their life expectancy to mortality to susceptibility to substance abuse.” On average, residents of distressed counties die five years earlier than those in prosperous regions; mortality rates from mental illness and substance abuse are 64% higher in distressed than in prosperous communities, a divide particularly visible in Appalachia and Native American communities. And despite the fact that 30 million more people live in prosperous areas, distressed zip codes contain three times as many people receiving SNAP benefits, and Medicaid spending per capita is double that in prosperous communities.

These divides are also drawn along demographic lines; over half the population in distressed counties are minorities, and majority-minority zip codes are twice as likely to be distressed. And despite the fact that Trump’s victory was largely attributed to white voters in mid-tier, at-risk, and distressed communities, the effects of community distress transcend demographic and political lines, and must be addressed holistically.

Which brings us back to the issue of growth. The driving factor behind this disparities, says EIG cofounder and executive director Steve Glickman, is the fact that “after the recession, the benefits of being in a large, economically diversified city that’s connected to the digital economy really went up, and the penalty for not having those characteristics became larger as well.” As places like San Francisco, New York, and Boston, continue to attract the lion’s share of venture capital funds as they sprout new businesses in new industries, places like Ohio, where business development and growth has stagnated, will continue to be left behind. “It’s a cyclical problem because when new businesses aren’t born, they can’t create new jobs that lure in good talent and a stable tax base,” Glickman says.

Bringing distressed communities into the fold of overall economic progress, then, requires building new businesses there. Matt Rizai, chairman and CEO of the software firm Workiva, Inc., was thinking along these lines when he established his company in 2008 in Ames, Iowa, drawn by the prospect of lower property values and a strong workforce. That mode of development–establishing homegrown businesses in less-trafficked regions–should be the focus, Glickman says. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s sort of low-hanging fruit in the policy debate that we should be setting up better systems of low-income debt financing and small business loans to get capital into these regions,” Glickman says. The Investing in Opportunity Act–a bipartisan piece of legislation led by senators Tim Scott (R-SC) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) and supported by EIG–creates a tax incentive for investors to fund initiatives in distressed areas.

Concerted policy efforts like these, Glickman adds, are a surer bet to distressed communities than trying to tempt large companies to set up shop. Amazon, for instance, has ignited competition among cities hoping to land the second headquarters of the retail giant (and the resulting $5 billion in community investment and 50,000 new jobs). The New York Times applied Amazon’s own requirements–from a high quality of life to a growing workforce–to the competing companies, and came up with a place not in need, like Jackson, Mississippi, but Denver, a city by EIG’s measure to be doing just fine. Welcoming a new Amazon headquarters, Glickman says, “would be equivalent to winning the lottery”: transformative, but vastly unlikely and unreplicable. What is needed to close the development gulf is a strong, concerted effort to rebuild the economies in distressed communities from the ground up.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)