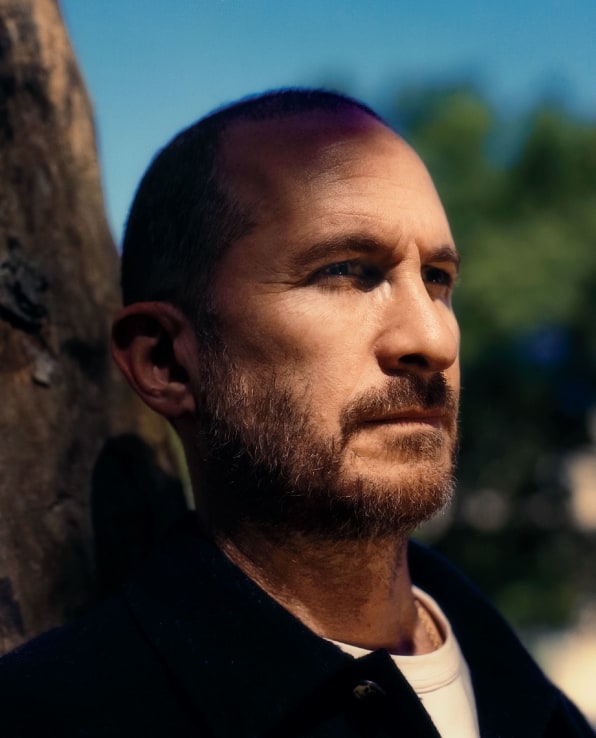

Human behavior isn’t always pretty. Darren Aronofsky makes sure we never look away.

Director Darren Aronofsky has a reputation for making audiences squirm. His audacious visual style and knack for pushing psychological buttons have allowed viewers to experience what it’s like to be a perfectionist ballerina trying to retain her sanity (Black Swan), drug users whose lives descend into hallucinatory chaos (Requiem for a Dream), an aging fighter unable to quit the ring (The Wrestler), and more. Lately, he’s been pushing himself—into new genres like National Geographic documentaries and YA literature. Aronofsky spoke from a shoot in Africa about balancing organization with improvisation, his upcoming film, The Whale, and the beauty of the internal monologue.

Fast Company: You’re in Zambia right now. What brought you there?

Darren Aronofsky: I’m in the Lower Zambezi National Park for a show I’m doing for Nat Geo [called Sentient]. We’re filming a pack of wild dogs, sometimes called [African] painted dogs. There’s a large pack of them, about 40. They hunt really big game. But before they go out and hunt, they actually vote in a unique way, to make the decision [about whether] to go out and hunt. The show is about animal intelligence, how the pre-21st-century idea that we’re very different from animals is untrue.

Environmentalism has been a focus of yours since high school, when you spent time in Kenya studying at the School for Field Studies. It’s woven into some of your films, such as Noah and Mother! You’ve also been producing numerous shows for Nat Geo. Has this been a conscious career evolution for you?

I’ve been a big fan of National Geographic my whole life. I subscribed as a boy and had those yellow-bordered magazines on my shelf. Getting to be more explicit with my activism [traveling to the Arctic to bring attention to drilling there, penning a New York Times op-ed about climate change] has been great because, unfortunately, this situation is really tough. It’s an all-hands-on-deck moment. I’m just trying to do anything I can to help.

In your new film, The Whale—which is based on the play of the same name by Samuel D. Hunter and hits theaters this fall—Brendan Fraser plays an obese man on the way to eating himself to death. He’s trying to mend relationships in his life. As a society, we’ve made progress in terms of destigmatizing body size, but there is still a lack of understanding, and prejudice. Were you nervous about tackling such a sensitive subject?

We spent a lot of time educating ourselves. There’s an organization called the OAC (Obesity Action Coalition), and they connected us with people who are living with obesity or for whom obesity has changed their lives in many different ways. To be clear, there are many people who are large and who are very, very happy and have a very positive outlook on the world. I think with this movie, it’s one story. For me, the greatest thing about film is that it’s an exercise in empathy. That feeling when you’re inside someone else’s head that is completely different from [yours]. I never danced ballet, and I never jumped off the top rope [in a wrestling ring], and I was never a drug dealer or user. So it’s about going on a journey with people and getting in their heads. That’s what brings us more together.

As a director, what’s in your own head when you show up on set on the first day? Do you have every detail worked out?

I don’t believe that whole myth of having a pre-thought-out plan. I don’t get that. I think you have to make things up in the moment, because no matter how much you can picture and imagine something, when you’re actually in that three-dimensional space with real people and real equipment and real actors . . . you have to allow the smells that are coming into the room or the mood that’s happening or the heat—they’re going to affect things. You have to be ready to capture and work with it all.

And yet you’re also known as someone who’s extremely organized and precise. You once said that if you weren’t a director you would have been a baseball umpire. How does this element of your personality play into your job?

My mom would pack two weeks before she went on a trip. And she’d get to the airport three hours early. Part of that rubbed off on me. I think it’s a big part of filmmaking, being organized. Because it’s an endless to-do list with an incredible [number] of obstacles. Unless you do your homework really, really well, all those roadblocks are going to destroy you and crush you.

People also assume you’re a math geek, based on your first feature, Pi, about a mathematical theorist obsessed to the point of madness by his quest to prove that everything in nature can be explained by mathematical patterns.

I had a class in high school taught by this teacher, Mr. Schneider, who basically taught a class on mystical math. Now it’s called Sacred Geometry, and is very popular. You’ll see it in new age bookshops and stuff. The high school class was all about these kinds of amazing facts about pi, the number, how it shows up in weird places. Really, that’s the idea that showed up in the movie. It just always stuck with me. It’s funny because Sean [Gullette], who stars in the movie, who was my buddy in college, was terrible at math. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind me saying this, but I doubt he could do long division. And he plays a math genius in that film. I really was never a math whiz. I was just fascinated by that character and by his unidirectional view of the world. He could have been a student of anything.

Monster Club, a YA novel that you wrote with your screenwriting partner, Ari Handel, was just released in September. A lot of people are probably thinking, “Wait, the guy who directed Requiem for a Dream wrote a kid’s book?”

My buddy Eric, when I was in elementary school, was a really good artist. He started this “Monster Club.” We used to draw monsters. Then at a certain point I wrote a script about it, but I never got around to making the movie. A friend who is a sci-fi writer asked to read one of my scripts and I was like, “Oh, read this one, it never got made.” He was like, “It would make a great YA novel—why don’t you turn it into that?” It was actually a really fun experience, because when you make a movie, you have to show everything. But when you write a book, you can have internal monologues. It really freed us. We’d run into a problem and we’d be like, “How are we going to do this?” And then we would remind each other that, oh, we can just have that character think it! It was fun.

A guide to Aronofsky’s ambitious projects of 2022—and beyond

Monster Club, HarperCollins

The first book in a young adult series, cowritten with Ari Handel, Monster Club is inspired by Aronofsky’s own experiences as a sixth grader in Brooklyn.

Limitless With Chris Hemsworth, National Geographic

Directed and produced by Aronofsky, this documentary series explores what it’s like to push the limits of human potential, both physically and mentally.

The Whale, A24

Brendan Fraser stars in this adaptation of a play by Samuel D. Hunter as a very obese man trying to reconnect with his daughter, played by Stranger Things’ Sadie Sink.

Protozoa Productions

Aronofsky’s company has numerous projects in the works, including Nat Geo’s Sentient; Kindred, an FX series based on Octavia E. Butler’s novel that premieres in December, and an adaptation of the book The Tiger, which will star Alexander Skarsgård and be coproduced by Brad Pitt.

(39)