IBM is putting up $25 million to help disaster response startups scale

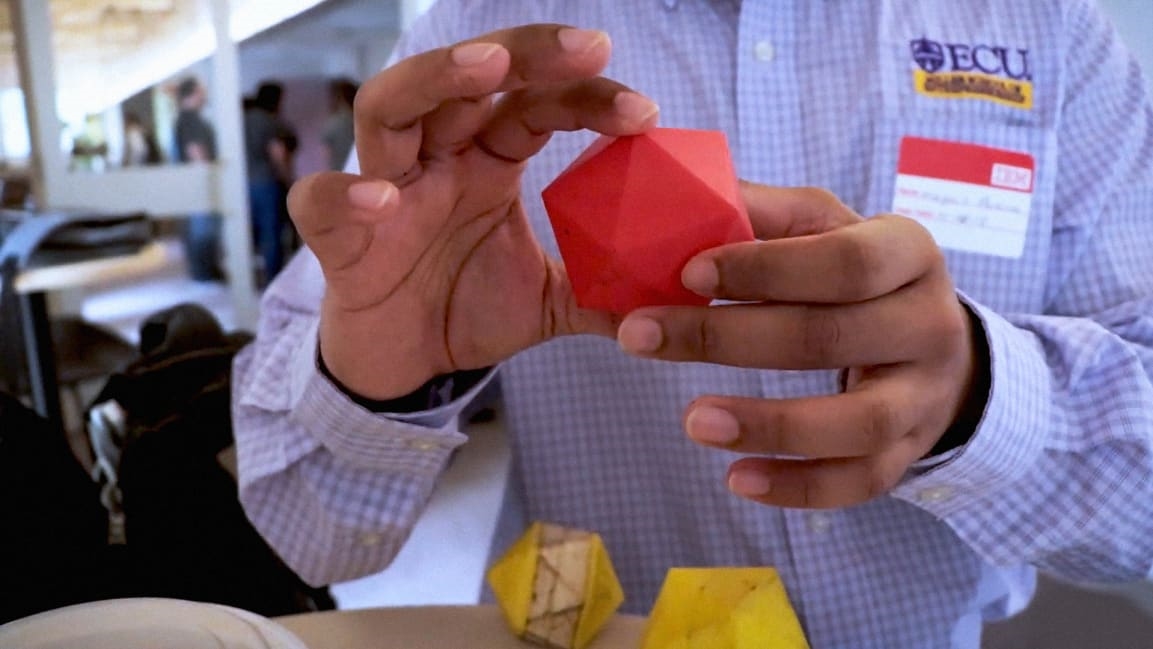

The specialized rubber devices will land in Puerto Rico this March. That’s when disaster response company Project Owl will deploy several flocks of “clusterducks”–hexahedronal balls with mini-Wi-Fi relays inside, inspired by rubber duckies–for a large field test. Each so-called “ducklink” works together to create an emergency mobile network wherever the devices end up.

To do this, the group will have lots of help from IBM. In late 2018, Project Owl (short for Organization, Whereabouts, and Logistics) won IBM’s inaugural Call for Code competition for new open-sourced disaster and recovery ideas. The now annual competition kicked off IBM’s five-year $30 million commitment to support more social impact projects. It drew more than 100,000 developers from 156 countries, with everyone competing for a shot at $200,000 in prize money, and the chance to be implemented by IBM’s Corporate Service Corps, a program from the company that offers IBM employees and tech to help cause groups, social good companies, and governments tap into promising concepts.

The Linux Foundation, which is also involved in the competition, ended up choosing 10 groups (including Project Owl) to be highlighted for further development. But IBM realized it could do more, so it just launched Code and Response, a four-year, $25 million commitment to help Call for Code winners test, deploy, and scale more quickly in the wild. (The 2019 Call for Code challenge focuses on natural disasters and especially improving community health and well-being as part of the preparation, survival, and recovery process.)

“[Call for Code] exceeded our expectations in terms of both the participation and engagement,” says Willie Tejada, the chief developer advocate at IBM. What the company had yet to figure out was their “implementation arm” would really look like. “Taking the footprint that we have in the corporate services crew, taking our own expertise on how hardened systems can be deployed at scale, how can we take it to the next level?” Tejada says.

The Project Owl pilot will be IBM’s first attempt at that. The startup plans to deploy 20 clusterducks, representing about 125 ducklinks, in Puerto Rico. Those will be spread out over a coverage area of about 20 to 30 square miles. “We’re going to pressure-test our system,” says Bryan Knouse, Project Owl’s CEO and cofounder. “How quickly can we get it out? How fast can this be done? How much does it cost? How many people do we need to do it? And [then we’ll] watch that data start flying across the system.”

Drones or a plane would likely air drop the ducks. Once the clusterduck turns on, people affected by hurricanes, earthquakes, or fires can use the makeshift hotspot to report more detailed information about their location and condition. Project Owl’s network also offers responders a dashboard of information to help formulate an action plan, including weather forecasts and the positions of different aid groups and their supplies.

If the Puerto Rico effort is successful, Knouse foresees a small live trial during the 2019 storm season and perhaps a larger real-time response by 2020.”We want to push as fast as we can to expand as fast as we can, but do it in the right scenarios and different places to really prove that this could work before we try and deal with a category 5 hurricane,” he says.

It would be hard for most small companies simply to orchestrate or afford such an effort of this size. But IBM is lending additional manpower, tech expertise, and industry connections to make it possible. That includes a partnership with the groups that could actually benefit from this intel, like the American Red Cross and United Nations Human Rights.

In this case, Project Owl’s maiden flight will be joined by DroneAid, another IBM incubated effort that uses drones to find and read emergency messages that people in unreachable places often leave on the ground, by using specialized mats with various machine-readable icons that can be left out on streets or rooftops. Using that information, a drone force could quickly map, tabulate, and relay emergency needs. Those drones could even be citizen piloted, and the same mats might eventually double as landing pads for drone-delivered supplies. Pedro Cruz, DroneAid’s founder and a self-taught developer on the island, won a Call for Code hackathon there last year.

Cruz personally weathered Hurricane Maria and subsequent storms. When communications went out, he used his drone to check up on his grandmother, who eventually died from complications around medicine shortages. “The most important things for anyone who goes through a natural disaster is being able to communicate with your friends, with your family, making sure everyone’s okay,” he says. “Basically imagine DroneAid as messenger pigeons.” In that way, DroneAid might help Project Owl with additional intel for their dashboard.

That’s exactly how IBM is hoping its Call for Code ecosystem will work. “It’s an absolute intent to take the principles of how you operate in open-source communities and apply those to both of these initiatives,” says Tejada. “When we talk about the three pillars of how we’re engaging with developers and large companies, it’s around code, it’s around content, and the last pillar is around community.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(8)