Inside the design drama of a century: The fight over New York City’s subway map

In 1978, The Cooper Union, an art school in New York City, held a debate between two designers that would determine the future of information design for the largest public transit system in the world. But proof that it happened was elusive until now.

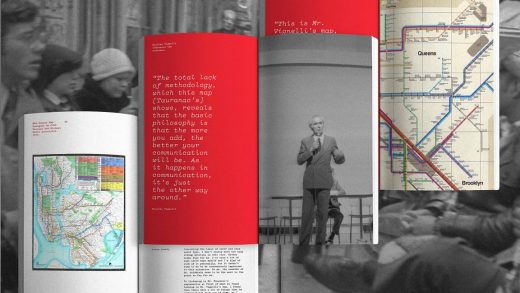

Last summer, filmmaker Gary Hustwit found a recording of the event that had never been made public. Hustwit, along with Standards Manual and design agency Order, is now publishing a transcript of the recording and images for the first time in a new book called The New York City Map Debate, with a foreword by Pentagram partner (and map lover) Paula Scher. The transcript reveals entreaties and insults. Powerful evidence backing each side. At the end of the day, it wasn’t just a heated design drama. It was a microcosm of shifting design tastes away from stripped down minimalism—and the result had real implications for subway riders for decades. “The ideas here about communication, about data visualization, about how to present a lot of complex information—some of the ideas from both sides still apply [today] even though we’re barely using paper maps,” Hustwit says.

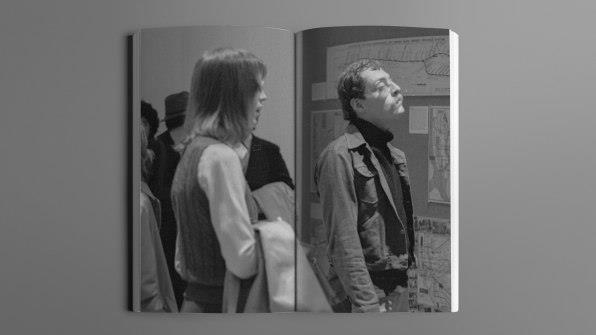

Hustwit had spent the previous summer digging into the history of the New York city subway map for a short film in coordination with an update of the city’s subway map, and had heard of the debate but couldn’t find details. He got in touch with Cooper Union, which as chance would have it, had just tracked down a recording in its archives. He then found the photographer of that night’s event, Stan Ries, who discovered photographs he had completely forgotten about in a storage unit. All of these artifacts went into the book collaboration with Order and Standards Manual, which has produced other beautiful books on design history, from NASA’s worm logo to the official symbol of the American Revolution Bicentennial.

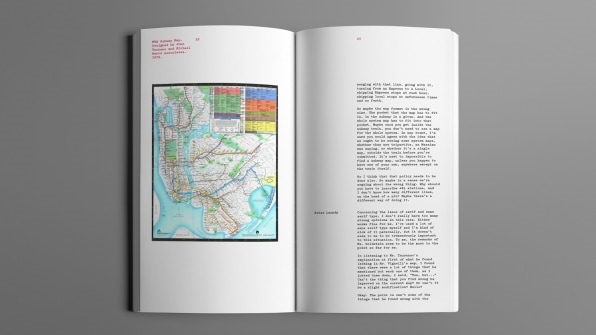

So how did something seemingly mundane, like a map, become a flashpoint? It started several years prior, in the early seventies, when the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) released a map designed by famed modernist designer Massimo Vignelli and his firm Vignelli Associates, which he founded after leaving the design firm Unimark. (His former Unimark partner Bob Noorda helped design the MTA signage project in the ’60s that preceded the map; Unimark lead designer Joan Charysyn also contributed.)

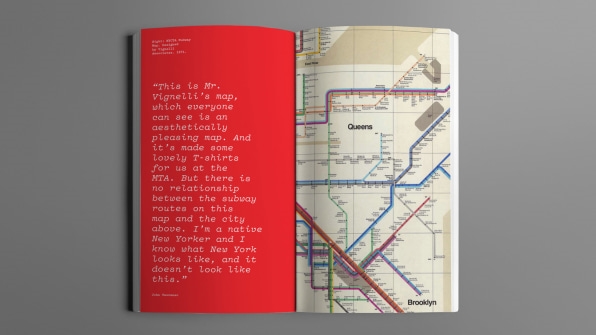

It’s a beautiful, simple diagram that gave subway riders only the information they needed and not a pen stroke more. Subway lines appeared in just 45 and 90 angles and every stop was marked by a dot. It was a breeze to read, but its layout didn’t correspond with the geography of New York City, and it didn’t show any above ground streets.

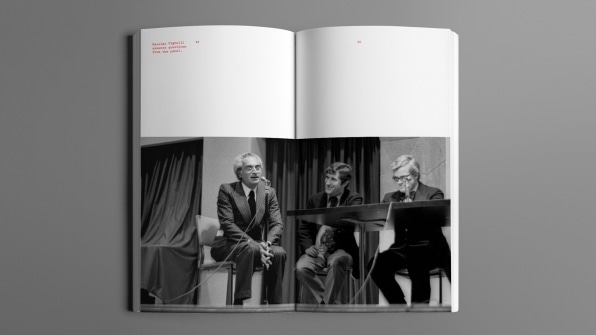

To Vignelli, those were unnecessary details. But it created confusion, according to Hustwit. And a counter movement to replace it emerged, led by the chair of the MTA Subway Map committee, John Tauranac. Tauranac worked with design firm Hertz Associates to develop an alternative map that showed more information about the city and streets. “Vignelli had stripped down [the map] with as little as you need,” Hustwit says. “Tauranac wanted as much information as possible.” The stage was set for when it all came to a head in 1978: Would the city’s subway map be minimalist? Or maximalist?

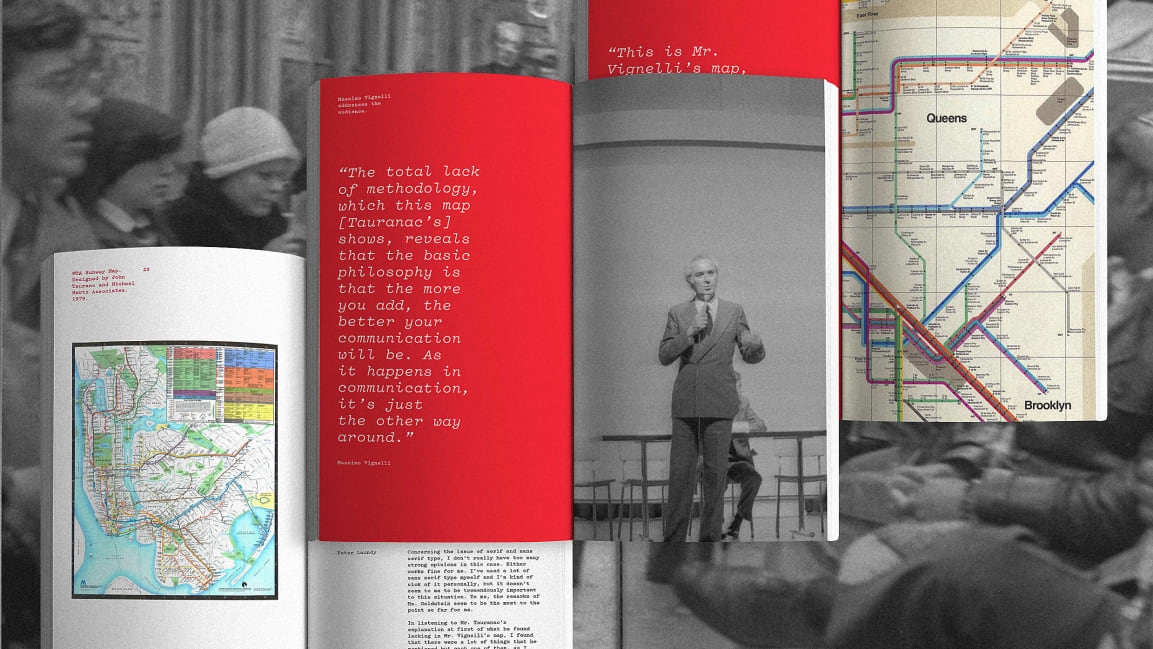

The designers met at The Cooper Union to make their respective cases. There were six other experts on a panel, and an audience of designers, subway riders, MTA employees, and a “motley crew” of interested members of the public who were in favor of one design or the other, according to Hustwit. In the words of Hustwit, it was a “design versus non-design showdown.”

Vignelli pointed to his map’s simplicity and rationality, methodically showing subway maps around the world as precedent. Tauranac made the case that it should resemble the geography of the city as much as possible. Ultimately, it came down to politics, personalities, and people who “really hated” the Vignelli map, according to Hustwit. “The total lack of methodology, which this map [Tauranac’s] shows, reveals that the basic philosophy is that the more you add, the better your communication will be,” Vignelli said. “As it happens in communication, it’s just the opposite way around.” Tauranac countered: “This is Mr. Vignelli’s map, which everyone can see is an aesthetically pleasing map. And it’s made some lovely T-shirts for us at the MTA. But there is no relationship between the subway routes and the city above. I’m a native New Yorker, and I know what New York looks like, and it doesn’t look like this.”

Ultimately, the result was written on the wall, according to Hustwit. Tauranac armed himself with rider polls and lobbied the city; Vignelli did not. “[Tauranac] was more tapped into that world,” explains Hustwit. Minimalism be damned, Tauranac’s map won.

The debate got at some pretty existential design questions. “How much information do you need to communicate something?” asked Hustwit. Determining the right amount of information, the right design or visualization for each context is “the challenge any communication designer faces,” Hustwit says, whether it’s one word or an entire brand. These subway maps exemplified two opposing approaches.

But this wasn’t just some heady design debate with no impact on everyday people. It has shaped how New Yorkers and visitors got around—and even how they saw the city for decades. “It did [have design implications] for New York design because the subway map is this iconic thing so many designers revere,” says Hustwit. “It’s the lifeblood of the city that uses public transportation.”

The debate was also a microcosm for a larger shifting of the design winds in the late seventies, with Vignelli’s map as collateral damage in the move from modern minimalism to postmodern maximalism. “[Vignelli] was trying to bring order to a very chaotic environment through design. Through the signage of the subway and the map, it was his way of trying to bring logic and clarity and clear communication to a city that was not about it at all,” says Hustwit. “He tried to use graphic design and wayfinding to clean it up. Looking back, it was a futile attempt.” Hustwit kindly suggests that both sides won: Vignelli’s 1972 map is now considered a work of art, and Tuaranac and Hertz’s late ’70s version lives on in subway cars to this day.

But Tuaranac’s map is far from perfect. As my colleague Mark Wilson wrote last year, “It’s more geographically accurate, but it actually condenses information that was in the Vignelli map. For example, it combines individual train lines such as the C, D, and E lines into singular trunks.” That makes it difficult for the MTA to convey when individual lines are not running or have been rerouted. So the MTA and design agency Work&Co tried to rectify some of the problems in Tuaranac’s map with an app released last year. It combines the best of both the Vignelli and the Tuaranac maps—let’s just call it a truce.

(56)