Is It Fair To Call Digital Health Apps Today’s “Snake Oil”?

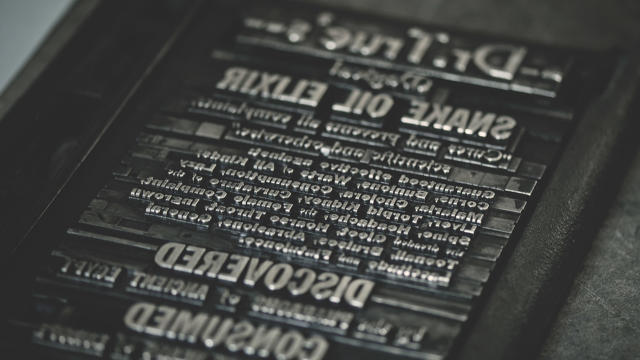

Back in the middle of the 19th century, the American Medical Association declared war on the so-called “snake oil elixirs” that were all the rage. Today, it has identified a new target: digital health apps.

In a speech delivered at the AMA’s recent annual meeting, CEO James Madara described the digital health industry as peddling apps and devices that “impede care, confuse patients, and waste our time.” Without naming names, he referenced ineffective electronic medical records, direct-to-consumer digital health products, and apps of “mixed quality.”

“This is the digital snake oil of the early 21st century,” he declared.

Before evaluating these comments, it’s worth taking a moment to define digital health. Author and cardiologist Eric Topol describes it as the “digitization of human beings,” which certainly sounds like the stuff of science fiction. After four years of reporting on the topic, I still struggle to come up with a working definition. Instead, I prefer to think in terms of categories: wellness (weight loss apps, fitness trackers) and IT (tools for browsing health insurance options, medical record systems); regulated medical devices (FDA-approved cardiac-event recorders, apps for measuring real-time blood loss, clinical decision support tools); and the “gray area” stuff in between (some diagnostic tests).

However you choose to define it, digital health is nothing new. But in recent years, it has recently gone mainstream thanks to investors pouring capital into the space in the wake of health care reforms, including the Affordable Care Act and the lesser-known HITECH Act. In 2015 alone, digital health startups amassed a mind-boggling $4.3 billion, according to early-stage venture firm Rock Health.

In a section of its website dedicated to digital health, the AMA concedes that “health care is evolving rapidly.” So why the harshly worded treatment now? And what specifically does the association mean when it refers to some digital health applications as “snake oil” and others as “really remarkable tools.”

From Darling To Digital Snake Oil

When I first started writing about digital health in 2012, most groups I spoke to seemed cautiously optimistic about the coming onslaught of new health-related apps and devices. The feeling was that health care was far behind virtually every other industry when it came to technology adoption, which remains the case. (I wouldn’t be surprised if hospitals and clinics were singlehandedly keeping fax machines in business.)

Back then, much of the skepticism around health technology from the AMA and other prominent medical groups was primarily directed at electronic medical record vendors. The HITECH Act of 2009 had incentivized health providers to adopt this technology to the tune of $30 billion. What that legislation did right was to promote adoption, but it largely failed in its mission to achieve widespread data-sharing between these systems. Moving a patient’s record from one health system to another is still often an expensive and time-consuming feat.

Meanwhile, developers newly drawn to health care pushed thousands of apps to the Android and iOS app stores. And many of the big tech companies, such as Apple and Alphabet, cast their eyes to health care, a $3 trillion sector. Some of these startups evaded federal regulators by remaining firmly in the “wellness” category, while others took established offline programs for behavior change and added a digital component. The latter are known as “digital therapeutics” in the startup vernacular.

For a few years, these companies were largely seen as ineffective and, at worst, a waste of time. But that changed last year when a series of high-profile health-technology companies were called out for deceptive marketing and claims, as well as in delivering inaccurate results to patients. Federal agencies, most notably the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), started seriously paying attention to the apps that lack scientific support to back up claims for products that claim to prevent or treat health or disease-related conditions.

But it wasn’t until the high-profile crackdown on Theranos, the much-hyped blood testing company, that the digital health industry came under fire. Theranos claimed its technology was revolutionary, but investigators found serious deficiencies with its lab that posed serious health risks to patients. Moreover, also in 2015, many researchers started publishing studies showing that health apps rarely delivered improved health outcomes to patients and/or published inaccurate health information. AMA’s Madara defended his comments to Stat News on Friday, citing one such study that looked at more than 1,000 health care apps for patients—and found that just 43% of iOS apps and 27% of Android apps were likely to be useful.

Industry experts I spoke to say the atmosphere around digital health startups has shifted. “In my conversations with digital health companies, there’s an understanding now that they need more data to back up their claims,” says UC San Francisco cardiologist Ethan Weiss, who advises a handful of digital health companies. “And entrepreneurs are really being asked to demonstrate that to the feds, particularly FTC.”

A Balanced View

Even advocates of digital health that I spoke to couldn’t outright refute Madara’s claims. But it is also true that digital health is a very broad category, and not every app is created equal.

“There are certainly those who make outsized and improbable claims for the efficacy of their digital health solutions—and they will get in trouble with the regulators,” says Farzad Mostashari, founder of a health-technology company called “Aledade” and the former chief at ONC, which sits in the Department of Health and Human Services. “Digital health can work miracles if embedded within new delivery models, and part of a new value system for the health care industry,” he adds.

In other words, it’s unfair to paint digital health with a broad brush. Those I spoke to in the industry and on social media pointed to companies like AliveCor, which provides an FDA-approved smartphone app to detect cardiac issues, and Omada Health, which has based its diabetes prevention program on government-backed research. These apps are focusing on underserved areas of traditional medicine, such as preventative care and chronic disease management. And they are a world apart from an app like iBipolar, which advised its users with bipolar disorder to drink hard liquor during a manic episode.

Ultimately, I only see it as a good thing that digital health companies as a whole are being held to a higher standard. And that’s particularly the case for those that claim to assist with diagnoses or disease outcomes. But there’s a tendency in any industry to fear anything that’s new—and I wouldn’t want to see that to be an excuse to shy away from new ideas. The very broad industry that is digital health is still nascent, and it needs to be treated with healthy skepticism but also an openness to new ideas that are backed up by evidence.

As Bob Wachter, associate chairman of University of California, San Francisco’s department of medicine, puts it: We can get to a really wonderful place—and we probably will—but we’re not there yet.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(20)