One man’s (maybe) quixotic quest to revive American manufacturing

By David Lidsky

Bayard Winthrop was evangelizing for investing in American industry long before it was cool. He started the apparel brand American Giant in 2011, and the founder and CEO quickly won acclaim for “the greatest hoodie ever made.” But the larger conversation Winthrop wanted to have about the benefits not only of buying American but more importantly, the downstream positive effects on the people and communities making those products was drowned out a bit amid the early 2010s optimism about the benefits of globalization.

In the wake of everything from COVID-19 and it elevating the issue of the need for resilient supply chains to the U.S. government’s shifting trade and industrial policy that prioritizes domestic production, Winthrop’s vision now appears prophetic. But as Winthrop will be the first to acknowledge, unwinding 40-plus years of neoliberal policies does not happen in an instant. American manufacturing may be witnessing a resurgence in support and conversation, but that doesn’t yet modernize local supply chains or the factories that once served as the bulwark of innumerable cities and towns across the United States.

Fast Company caught up with Winthrop to discuss this current moment, what still needs to be done to reorient American policy around production rather than cost, and how he met WeWork cofounder Miguel McKelvey and the impact the architect is having on American Giant. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

In preparing to chat with you, I was reading a Bloomberg story that just offhandedly referred to your effort to revive American manufacturing as perhaps quixotic. Eleven, 12 years into American Giant, where would you characterize your progress and mission thus far, on a scale of zero to quixotic?

In some ways, it is a quixotic endeavor. There’s a big divide happening now. Between this sort of neoliberal view of trade that simplified into, essentially, if we pursue unfettered free trade, we will lift the world up and we will open up China we will make the world a better place. By outsourcing manufacturing, the price of goods and the cost of production [will go down, and] we will replace those jobs with service sector jobs.

Then there’s the other side that says that is a complete misunderstanding of the way to approach the world. The cost of production and prices should not be at the forefront, but production should be. If you focus your trade policy and your economic policy on production, lots of good flows. From that you get not only good paying jobs and higher wages, but you get better communities. You get better capability domestically to respond to the things that the nation needs. You get more resilient towns and cities. We’ve spent 30-plus years, 40 years, pursuing that neoliberal idea and that came at a great cost. If you spend time in these communities, whether it’s urban or rural ones that used to be manufacturing centers—Baltimore, Detroit, rural North Carolina, or rural West Virginia, whether it’s Black and urban or white and rural or a combination of the two—the problem is the same and manifest. We have destroyed these communities that once were anchored around good, viable manufacturing jobs. In many cases, low-skilled jobs are gone. The cost to humans and communities has been just dire.

[Good] jobs are so fundamentally important and such an anchor to people’s sense of worth and well-being that I wanted to pursue a different path.

Is neoliberalism effectively dead or at least on its way out?

The implications of 40 years of foreign policy have become clear. China is not our friend. Rather than normalizing and entering into the first world order, China’s in many ways become the opposite; more intractable today than it was 40 years ago. There has been a great shift away from China basically providing the U.S. consumer with lots and lots of flat-screen TVs and cheap T-shirts.

We’ve lost our ability to make a lot of critical things, so there’s been a resilience impact as well. It’s kind of insane that we had to go to a T-shirt manufacturer in a panic as the federal government and say, we need you to convert [because] we couldn’t make medical gowns. We couldn’t make medical masks. That has really started to hit policymakers in the face, almost unavoidably so.

The most interesting thing about the Trump-Clinton [2016] election cycle was all of the energy in the electorate was with Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, both of whom were getting at this deep sense of malaise among working-class Americans and this intuitive understanding that we fucked things up over the last 40 years.

President Trump and President Biden [chose] U.S. Trade Representatives who are very much oriented around production versus consumption. That is starting to change at the administration level. With Trump pulling out of the TPP and Biden making moves with silicon chips, there are actual administration moves that are beginning to reorient the way that we’re thinking about things. [Since COVID], there have been absolute tailwinds. Brands are starting to look domestically, retailers are starting to look domestically. The manufacturing sector has benefited. My sense is that U.S. consumers are beginning to wake up to the idea that there’s a cost to the Amazonification of our economy.

A lot of things have happened in our trade policy in the past few years, but at the same time we’ve seen this pretty remarkable rise in Shein and Temu and their popularity in the United States. Much as we’ve had a national conversation around whether TikTok should be banned, should these also be banned or subject to the same kind of potential restrictions being explored for TikTok?

You’re getting at such a basic human question. I think about the TikTok example. We know it’s fucking bad for people. It’s bad for people like Mark Zuckerberg, who controls Instagram, that Instagram is really shitty for young kids. And yet, you don’t have the courage to stand up in front of Congress and say, we’re going to take this upon ourselves and limit access to 13-year-olds, we’re going to ban social media for kids 18 and younger, whatever it is. To me, it’s the same thing with Shein. The way that company operates, where its clothes are coming out of, the reality of what’s happening in Xinjiang, what it is doing to the domestic supply chain. . . . Those are bad things for us.

The question is not whether globalization is going to happen or not. It’s, how is it going to happen? To what extent should we nudge behaviors and policies in the direction that we know are going to benefit communities and individuals? We’ve been talking about innovation as it relates to getting cheaper consumer goods into the hands of consumers with more choice and more options, as opposed to saying no innovation should be happening in service of production and in jobs and in communities and in humans. To what extent does it matter to us as a nation and as a community—as individuals—that we take proactive action to help people? From a trade policy standpoint, from a domestic manufacturing standpoint, for a long time we have decided quite willingly to not only not prioritize, but to competitively disadvantage domestic suppliers. That’s just crazy to me.

What impact do you feel like American Giant has had on the communities in which it operates? Where have you seen the kind of change that you’re hoping to accomplish?

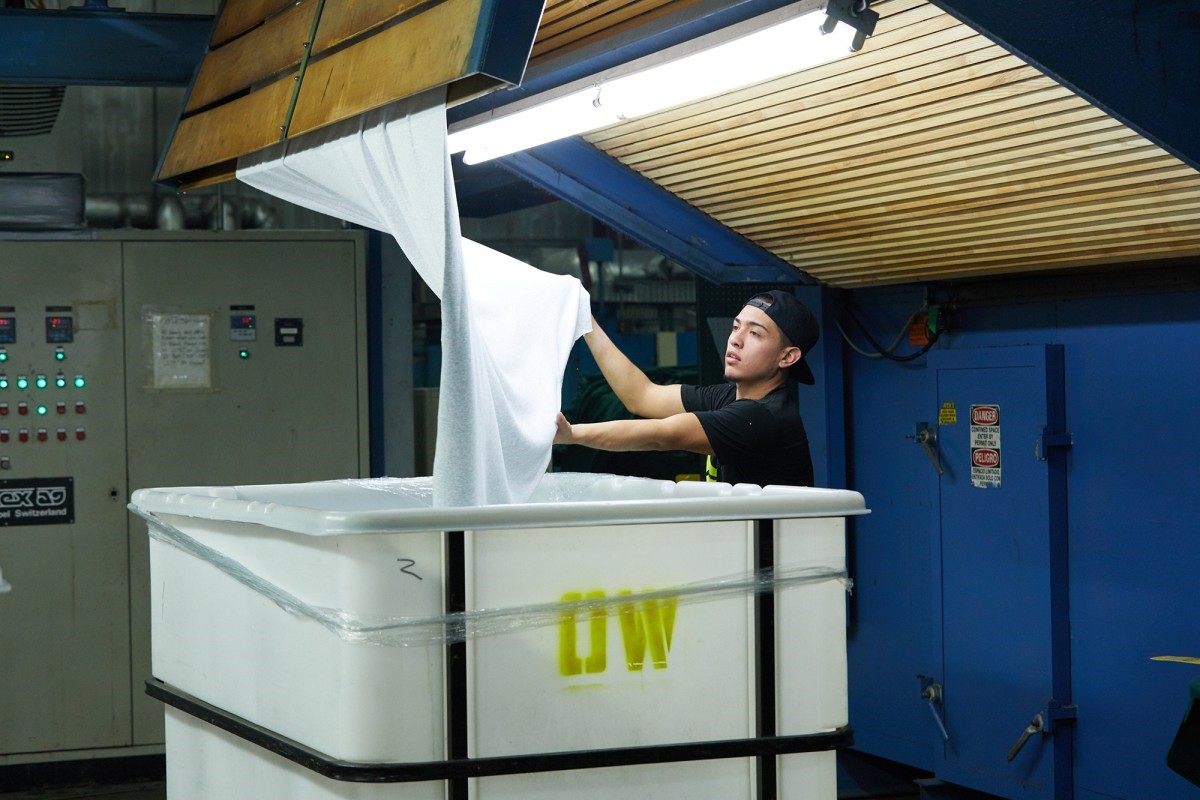

Scale matters a ton in that conversation, right? Economists will cite that for every manufacturing job, you create 2.68 [times the] impact benefit. That’s whatever that is. And all that probably is true. I don’t know, I’m not an economist. But the thing I’m struck by is if you go into, let’s say, Middlesex, North Carolina, where our primary East Coast production facility is, it does a bunch of T-shirts and sweatshirts for us. That place employs 100 people, a little more in the busy months. That’s a town that is probably like a lot of towns you drove through on the way to Florida. You can see the remnants of a main street; you can see lots and lots of manufacturing facilities all over the place. Now there are much fewer of those and boarded-up businesses on Main Street, but there’s our plant which is cranking, with a [full] parking lot. Those people eat at the local diner, and they use the local gas station. That’s the effect I’m struck by. There’s an echo effect that happens.

One version of this fight is American Giant trying to build its business customer by customer, and we’ve been doing that for 12 years and will continue to do it. But there are also the things that really begin to move [this] at a macro level. The federal government starting to bend policy to more support domestic capability. Big retailers making commitments, big policymakers making changes. The challenge that’s present throughout our supply chain is that [many remaining American manufacturers] are small, family-run businesses, oftentimes run by sons and daughters or grandsons and granddaughters with weak balance sheets. Unless they have long-term commitments or big orders, they can’t make the financial commitments to stay abreast of what’s happening in China, let’s say. You’ve got to break that cycle a little bit.

In our case, we have done that in our own small way by making a commitment to domestic made, and so we’re gonna be here for a while and so our partners can invest in it. But when you start to see the bigger changes, that creates a totally different framework to have the conversation because the volumes and the rules begin to change in your favor.

There’s a growing cohort of tech people who are committed to the idea of U.S. manufacturing. But it is generally in a sort of robots-as-a-service kind of way. It’s less about the jobs than just doing it in a sort of wholly automated way. What is your take on that vision for an automation-forward vision of American manufacturing and that narrative of, we’re not cutting jobs, there’ll be different jobs?

That’s obviously a really complicated question, but automation, innovation, robotics have got to be part of the answer. You can’t live in a world where you’re just stone aging the damn thing. My view is that you want to do two things in parallel: You want to create the environment for a competitive domestic production capability by conceiving and enacting trade deals that prioritize domestic production much the same way, by the way, that China does. China is a quite protectionist economy. They do that because they want to protect their own ability to be the best producer in the world. And in parallel to that, we’re going to innovate and invest in our capabilities as fast as we possibly can. We’re going to invest in the [manufacturing] sector and prioritize it.

What impact has Miguel had on the business?

I’ll give you an anecdote by way of getting to the question. He came with me at some point [during our discussions] on one of the supply chain tours, and we went through this facility in Gaffney, South Carolina, that is a yarning facility. It converts raw cotton into yarn. It is a very big facility, and it is highly automated. It’s filled with robots. When you and I were kids, that building employed about 1,000 people annually. Now it employs about 200 high-skilled operators and mechanics. They’re very good jobs. I was talking to the president of the company, and he was having a hard time getting people to take these jobs. I’m like, that’s crazy.

But Miguel, was like, it’s not to me. He said, I think working there would suck. There’s no natural light. There’s tons of ambient noise. I’m like, Dude, the option is to work at the local Chick-fil-A. He [replied], I think I’d rather work at the local Chick-fil-A where I can talk to the person next to me. He began to walk me down this journey of all the things that he would change if he was running [that factory].

We then went to this facility in Middlesex where we do our cutting and sewing. [Miguel] is a very smart human, and he listens a ton—unlike me—and our factory manager said one of our challenges is that we employ a lot of women, like 98%. A lot of them have kids, so we have to cut off shifts at 2:30 to get their kids. Miguel was like, why don’t we create an after-school program here? Why don’t we just knock down these walls in between these offices that we’re barely using and put in some laptops and some desks and have a tutor and provide them with snacks. So that’s an idea that is currently like getting cycled up internally. But that would never have occurred to me about the human factor of our operational stuff in that way. He’s also involved in other aspects of business, but he’s been very empowering about thinking about how do you innovate there, thinking the way that what these jobs need to be as it relates to just being a human being. Are people happy here? Can I make them happier? He’s been a great partner to me in that regard.

(13)