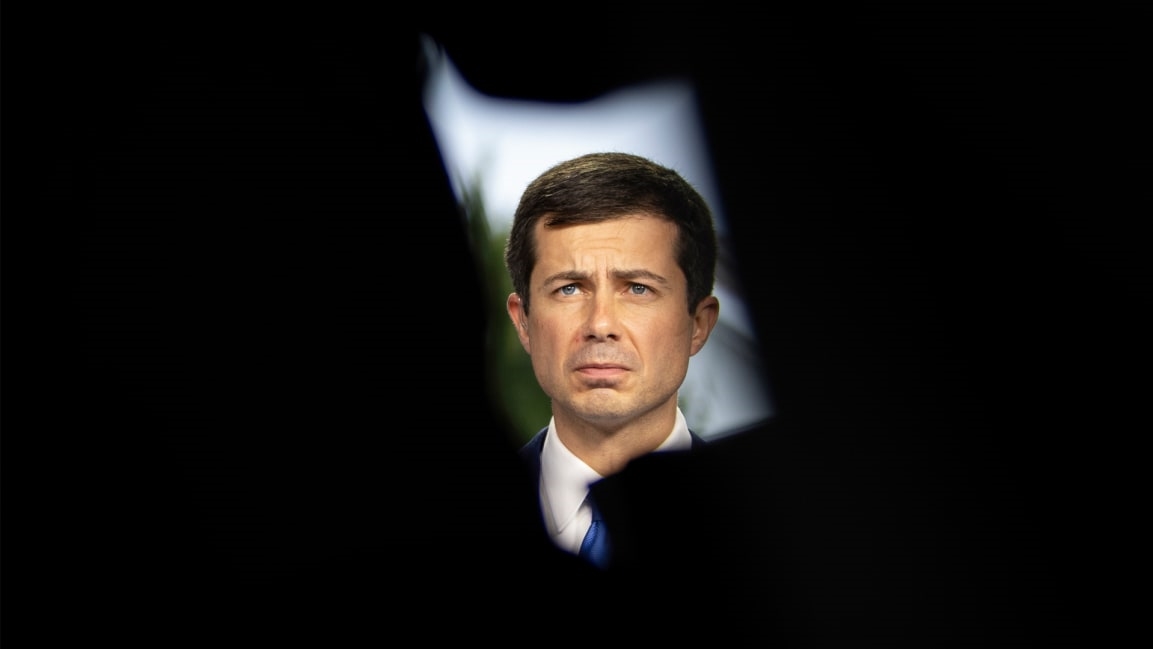

Pete Buttigieg getting attacked for paternity leave is why so many new dads don’t take it

Before U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg became a father of twins this summer, he made it clear he was going to take paternity leave to spend time with them and his husband, Chasten.

But a month later, he’s facing criticism for not being more present, as the United States must contend with a global supply-chain crisis that has slowed manufacturing and shipping, impacting everything from computer chips for new cars to grocery shopping lists and holiday gift buying.

Fox News ran a story about that earlier this month, and on Thursday, Fox News host Tucker Carlson mocked Buttigieg’s decision to take time off to be with his newborn twins, commenting, “Paternity leave, they call it, trying to figure out how to breastfeed. No word on how that went.” The DOT secretary shot back on NBC’s Meet the Press on Sunday and in an interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper, calling the work of fatherhood important.

Buttigieg also has said that he’s made himself available for urgent government matters, including the crippling supply-chain issues, any time of day or night. His paternity leave began in mid-August.

The person 14th in the U.S. presidential line of succession is likely the highest-ranking male government official to temporarily step away from work to tend to new babies. (The most recent baby in the White House was John Kennedy Jr., and how much time do you think JFK took?) But Buttigieg is hardly the only heavy-hitter to embrace paternity leave. Other notable on-point dads include Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg; Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanian; Toms founder Blake Mycoskie; and Dwyane Wade, then a Miami Heat shooting guard.

The average American dad takes less than a week off—usually the day of the birth and a few days after—according to Richard Petts, a sociology professor at Ball State University and a parental-leave expert. A long leave is very much a position of privilege.

“They are brave ones,” he says. “We’re not accepting of men in particular taking long periods of leave. There are assumptions that these are people of huge responsibility, and they should be at their jobs. We live in very work-first society. They should be thinking about quarterly reports.”

There is still a risk associated with taking daddy time. According to a McKinsey survey released in March, 20% of people they spoke to said the main problem with taking leave was the “risk of a career setback,” though most said the risk was worth it. For a man not at the apex of his professional life, that makes the prospect less attractive. Those in middle management, engaging in the blood sport of office politics, may see any time away from the office as lost opportunities to get ahead. This is magnified even more for men who are just starting out in their careers; the “paying my dues” and “be a team player” mentalities loom large.

“When men take paternity leave, they get punished,” says Josh Levs, author of All In: How Our Work-First Culture Fails Dads, Families, and Businesses—And How We Can Fix It Together. “You just had a kid. The worst thing is to lose your job or your promotion. They’re fired or demoted or lose job opportunities. Even when it’s available, the cultural stigma against it is so great.”

He cites male employees who’ve been summoned by bosses and are told, “We have paternity leave, but no one takes it,” and points out that paternity leave should not be a luxury or controversial.

And not everyone has the opportunity to even make the choice. The Society for Human Resource Management found last fall that while 55% of employers provide paid maternity leave, only 45% give paid paternity leave.

If a man can’t afford to step away from work and a paycheck, he won’t ask for paternity leave at a company that doesn’t provide all or some of his salary in his absence. Men in lower-paying jobs—or those just starting out in higher-paying professions, but not yet experienced enough to command hefty compensation—fall into this category. In homes where the man is the primary breadwinner, it’s even more acute.

“The vast majority of Americans don’t have access to paid leave for that long a period of time, and most people can’t afford to take 6, 7, 8, 12 weeks off with FMLA,” Petts explains, referring to the dozen weeks of job-protected, unpaid time off guaranteed by the Family and Medical Leave Act for the birth, adoption, or foster placement of a child. “The assumption is that the woman is supposed to stay home, so it doesn’t apply here. These are ingrained gender norms, this pressure and assumption that men are the financial providers. They need to focus on their carers and women need to tend to childcare.”

That narrow thinking leaves little room for families in which it’s two men with a new baby, like the Buttigiegs, and where it’s two women.

Meanwhile, public perception remains a big part of the issue. Ohio State University research from April reveals that about 50% of Americans give a thumbs-up to government-funded maternity leave, but only one-third said as much for paternity leave.

“There’s a misunderstanding broadly across our society about what dads do at home,” Levs says. “People have internalized these images of dads as buffoons, as irrelevant. When a guy says he’s taking paternity leave, there are bosses generally thinking, ‘He’s getting paid to stay home. He’s drinking beer and watching sports.’”

(56)