Post-‘Roe,’ design is crucial for abortion access. But it’s far from enough

Tampons. Breast pumps. Forceps. These tools have vastly improved reproductive health, and yet they’re rarely seen as great works of design.

Designing Motherhood, a new exhibit at the MassArt Art Museum (MAAM) in Boston, wants to change this. The show is based on a book of the same name by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick that came out last fall; it explores more than 80 designs that have defined the arc of human reproduction, from conception to postpartum.

At a time when abortion access is being curtailed around the country, the exhibit offers clues about how design might help women circumvent the system and regain some measure of control over their bodies—but also about how limited these design interventions are without systemic change.

In the U.S. and around the world, women’s reproductive healthcare is marginalized, resulting in high rates of unwanted pregnancies and maternal mortality. Millar Fisher, who co-curated the MAAM exhibit along with four other curators, says part of the problem is that it’s still taboo to discuss pregnancy and childbirth.

Since women haven’t felt comfortable talking about issues like ending a pregnancy, vaginal tearing during childbirth, and nipple pain from breastfeeding, there hasn’t been a concerted effort to develop solutions. Often women have had to band together to design products themselves, using whatever tools they have at their disposal.

[Photo: Yukai Chen M’23/courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

As Millar Fisher and Winick worked on the book, they encountered a lot of resistance from publishers who thought the topic wasn’t important enough.

“We pitched it and pitched it, and everybody said it was too ‘niche’ a topic or it was a ‘woman’s issue,’” Millar Fisher says, noting that it was only when she received the support of nonprofits devoted to childbirth—including the Maternity Care Coalition in Philadelphia and the Neighborhood Birth Center in Boston—that the project got off the ground and MIT Press agreed to publish it.

[Photo: courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

Throughout the exhibit, we see examples of technologies and devices that have helped the reproductive process, including menstruation and contraception. It’s remarkable how often products came about by accident, rather than because a company was eager to serve women’s needs.

For instance, there’s an early tampon manufactured by Tampax in 1936. During World War II, Kimberly-Clark developed a material called Cellucotton to absorb soldiers’ blood. Nurses on the battlefield realized they could use it for their periods, which spurred several companies to produce pads and tampons from the material.

The first epidural, meanwhile, was developed in 1885 by the Spanish military surgeon Fidel Pagés Miravé to treat wounded soldiers by injecting cocaine into their spine. Later, it occurred to doctors that this could help people in labor and they began injecting a cocktail of anesthetics into patients’ spines before delivery. Today up to 70% of U.S. births involve epidurals.

In many other cases, women have had to work together privately to solve problems. A large part of the exhibit is devoted to midwives, who have been responsible for delivering babies for most of human history.

In the U.S., the practice was often rooted in the wisdom of Indigenous and Black women. (It wasn’t until the 20th century that childbirth was relocated from the home to the hospital, where it was presided over by doctors who were predominantly white men.) These women developed breathing techniques to ease labor pains and came up with hygiene practices, such as cleaning surfaces with alcohol, that are still used today.

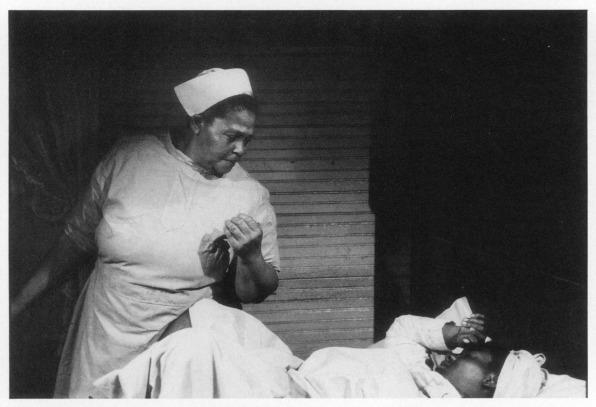

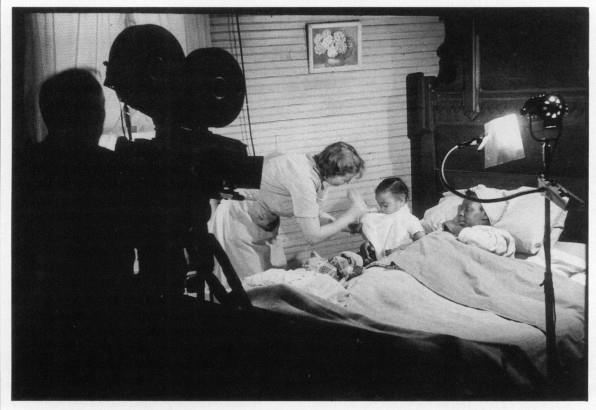

[Photo: courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

The exhibit features a 1953 film called All My Babies, which was commissioned by the Georgia Department of Public Health as a training aid for midwives. It shows how Black midwives provided critical care to poor, rural women across the South and delivered babies at home. It also shows two births.

“It’s perhaps my favorite part of the entire exhibit,” Millar Fisher says. “The director was inspired by the work of Italian neorealist directors, and shot using nonprofessional actors.”

[Photo: courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

The shift from midwifery to hospitals underscores another big theme of this exhibit, which has to do with the way government policy intimately influences women’s bodies and how life is brought into the world. Take, for instance, the concept of the “baby box.” Starting in 1938, the Finnish government provided low-income people with a cardboard box with all the things they’d need after giving birth. This included everything from clothes and books to postpartum underwear for recovering mothers.

In 2017, the Scottish government developed a similar box to be given to every single baby born in the country. “This is an example of great design, since the box itself can be used as a crib,” says Juliana Barton, who helped curate the exhibit. “But it also reveals that design comes in the form of good policy. Government plays a central role in every part of the reproductive journey.”

[Photo: Yukai Chen M’23/courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

This couldn’t be more true in our present moment, with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. There’s a device from 1971—at the very start of the exhibit—that reveals the lengths to which women had to go to take control over their bodies before abortion was legal. It’s a glass jam jar, with a valved syringe that serves as a low-cost abortion device. It was developed before Roe was passed in 1973, at a time when women in the U.S. and around the world were fighting for access to abortion. It was used in the early weeks of pregnancy by inserting a tube into the cervix using a speculum until it reached the uterus. By activating the syringe plunger, it created a vacuum, which would extract the contents of the womb into the jar.

[Photo: Yukai Chen M’23/courtesy MassArt Art Museum]

The curators of this exhibit point out that we’re seeing another wave of innovation in response to the fall of Roe. In some states where abortion has been rendered illegal, there are discussions about ways to make it easier for pregnant people to get medical abortions secretly. And on a legal front, activists are fighting for state-level legislation that will protect abortion-seekers.

“As the exhibition points out, design is not just about objects,” Millar Fisher says. “It is also systems that impact how we live our lives.”

(17)