POV: The OceanGate Titan’s disappearance highlights the dangers of the startup ethos at sea

By S. A. Applin

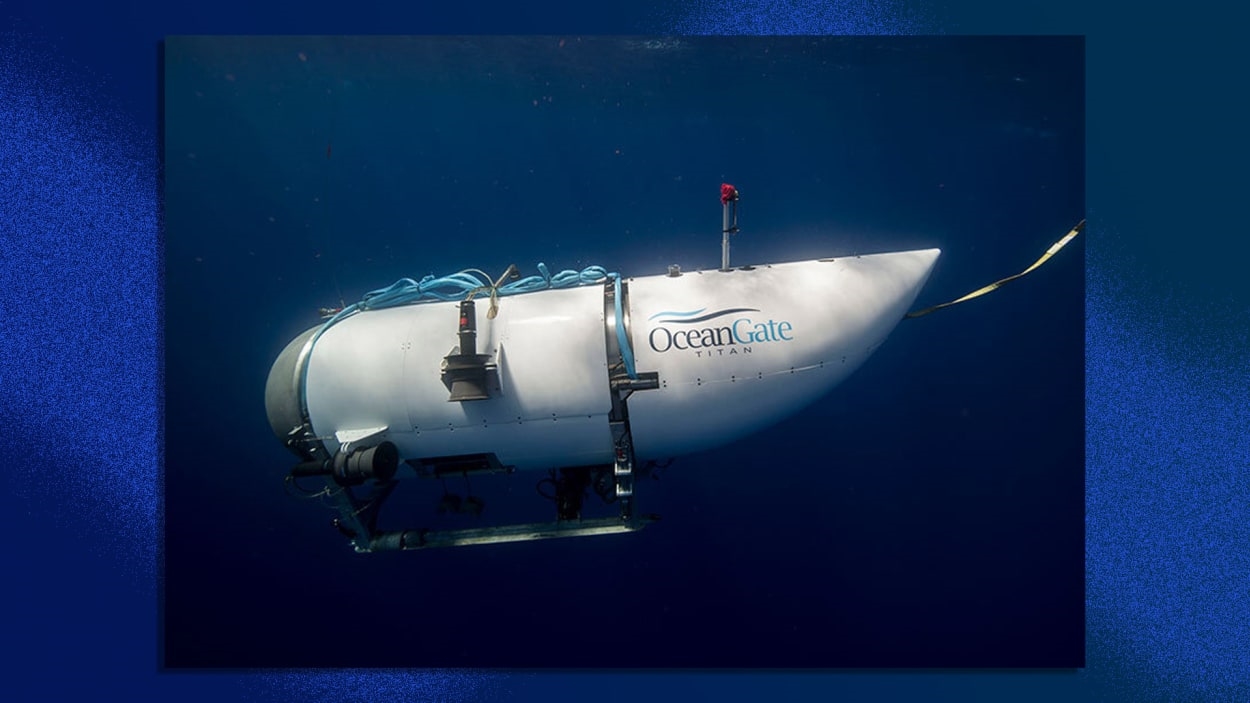

Right now, the world remains gripped in the race to discover OceanGate’s Titan submersible that’s been lost in the Atlantic since Sunday. There are five people aboard the tiny craft, and air is quickly running out.

No matter the outcome, there’s only one way we can look at this situation: OceanGate’s Titan—which took tourists to see the wreck of the Titanic—is an experiment as much as it is a commercial enterprise, and its participants (who paid $250,000 per ticket) were the guinea pigs.

Titan is a cross between high-tech engineering for pressure resistance—OceanGate consulted with NASA on the craft, though the agency was careful to clarify that it didn’t build the vessel—and low-tech jury-rigging. For steering, the Titan relies on a Logitech F710 Wireless PC Gamepad controller. GPS and wide-band communication are not on board but rather communicated via brief texts enabled by a sonar acoustic link. Passengers sit barefoot on the floor with no seatbelt, cushioning, or any other human comfort aside from a rudimentary “toilet.”

OceanGate, the company that arranges and conducts these voyages, has only been operating the Titan since 2019, but has been wrapped up in legal battles since before it publicly debuted. A former employee and submersible pilot, David Lochridge, alleged in a 2018 counterclaim lawsuit that he was fired for sounding the alarm on safety issues aboard the Titan. (This came after he was sued by OceanGate, with the company claiming he breached his employment contract by whistleblowing to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.)

Of critical importance in Lochridge’s counterclaim suit was the “viewport” (e.g., window) that was only rated for “a certified pressure of 1,300 meters [4/5 of a mile], although OceanGate intended to take passengers down to depths of 4,000 meters [nearly 3x more].” Furthermore, “OceanGate refused to pay for the manufacturer to build a viewport that would meet the required depth of 4,000 meters,” his legal filing stated. In a letter sent around the same time to CEO Stockton Rush (on board and now missing), many other “industry leaders, deep-sea explorers, and oceanographers” also warned of Titan’s potential fatal flaws.

The motto, “Fast, cheap, or good; pick two” has been repeated in engineering circles for decades. Unfortunately, when these scenarios play out in real life, it’s “good” that’s often left by the wayside. That might be fine enough when the design is for a new drawing app, but it can have grave consequences in matters of transportation or other contexts that can impact human life.

But such is, often enough, the ethos of “disruptive innovation.” Deep-ocean exploration is one of the few remaining challenging frontiers on our planet and a fertile ground for unregulated innovation. As such, OceanGate was able to rely on shockingly primitive tech, more along the lines of what a startup would do, rather than an established, regulated transportation manufacturer. OceanGate relies on Elon Musk’s brainchild, Starlink, to have a robust connection. Launched in 2019 (around the same time that Titan started its tours), Starlink deploys nearly 4,000 satellites into low Earth orbit. But its network has only been up for four years. Is it robust? Are there different software versions running on different satellites? Is it something you would want to bet your life on in a submersible being driven by a game controller with a window not rated for the depth you’re traveling?

So, too, is humanity’s hubristic belief in its ability to conquer nature’s most ominous depths—a conviction for which the privileged are willing to shill out great sums. Billionaires (and there are two lost with the Titan) can buy any object, but high-status adventure is harder to come by. Titan offers a fast track to explorer status, with relatively little training required. It’s exclusive, with waiting lists and high costs—and provides a once-in-a-lifetime experience that few have obtained.

In a short video clip, OceanGate’s Rush, said, “I’d like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General McArthur who said, “You are remembered for the rules you break.” And, you know, I’ve broken some rules to make this. . . . It’s picking the rules that you will break, which are the ones that will add value to others and add value to society.”

It’s unlikely Rush intended it because the rules he broke have already caused serious consequences, but Titan’s flaws may well end up persuading a future generation of submersibles to put safety first, and to teach future startups that there might just be a reason so much of the ocean is unexplored.

S. A. Applin is an anthropologist whose research explores the domains of human agency, algorithms, AI, and automation in the context of social systems and sociability. You can find more at @anthropunk, PoSR.org, and @anthropunk@federate.social.

(10)