Putin’s Regime Influences Facebook In Russia, Too, Even More Blatantly

Amid the outcry over Facebook enabling ads linked to a Russian propaganda operation to be seen by millions of American voters during the 2016 election, the social network is taking steps to reassure the public. In full-page ads in Wednesday’s Washington Post and New York Times, Facebook asserted that “We take the trust of the Facebook community seriously” and “We will fight any attempt to interfere with elections or civic engagement on Facebook.”

At least some of the ads seemed designed to stir up tensions and rile U.S. extremists. One ad, for instance, featured photographs of a black woman pulling the trigger on a rifle and could have been designed to promote racial discord, while others promoted anti-immigration rallies, reports the Post.

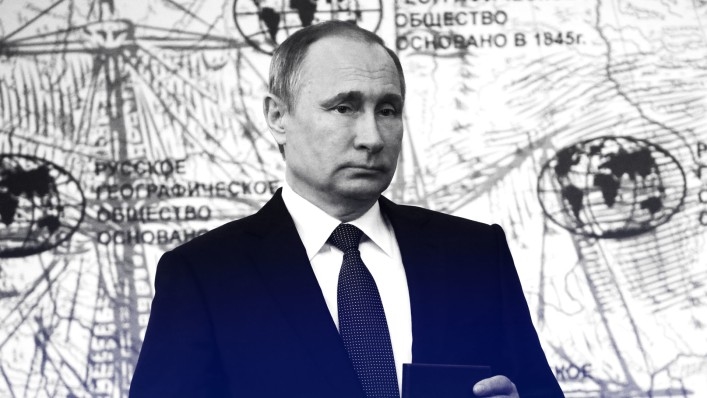

But while Facebook has now vowed to adopt measures such as hiring thousands of election integrity specialists to prevent such a recurrence of meddling in U.S. elections, its commitment to civic engagement and election integrity has long been questioned by activists in Russia itself. Not for helping spread fake news and propaganda, but for bowing to pressure to block content posted by opposition figures struggling to have their voices heard amid the increasingly autocratic rule of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

According to Facebook’s own data, the company restricted access to 251 “pieces of content” upon request from Russian regulators last year, up from just 84 the previous year, and the same number in 2014. The posts allegedly violated various “local laws related to extremism, alcohol sale, illegal gambling, and the promotion of self-harm and suicide,” Facebook said in an annual report on legal requests received around the world.

But experts have said for years that Russian authorities abuse such requests to take down non-extremist posts that offend Putin’s regime, like an event page promoting a rally in January 2015 for prominent opposition candidate Aleksei Navalny.

“The extremism label is something that is used and abused to shut down things that we wouldn’t necessarily recognize as in any way extreme,” says Keir Giles, a fellow at the U.K’s Chatham House. “It’s really a way of using the very vague legislation to shut down things the authorities don’t like to see online.”

Kremlin’s War On The Internet

And Facebook, critics have said, is too quick to take authorities’ word about what constitutes extremist content. So while Russian authorities post propaganda and rumors to interfere with “civic engagement” abroad, their colleagues can disrupt political discussions at home by issuing overly broad takedown requests to the influential social site.

Facebook isn’t the only social media service to receive or heed such requests: Twitter saw 2,118 takedown requests from Russian authorities last year, compared to 1,797 the previous year, and just 121 the year before that, according to its own transparency report.

A Facebook spokesperson declined to comment on any potential policy changes, and Twitter didn’t respond to a request for comment. Weir says it’s hard to know if revelations about Russian manipulation will have any effect on the social media companies’ policies toward Russia itself.

“It’s very hard to tell, because what we need to remember is these are multinational companies that have on more than one occasion demonstrated their primary interest is not necessarily defending Western values and Western societies,” says Giles.

The Kremlin began to look at regulating internet content in earnest in 2012, after officials saw social media used to organize major protests in Moscow and to coordinate the Arab Spring protests in the Middle East, says Andrei Soldatov, author of The Red Web: The Kremlin’s Wars on the Internet. The Russian government effectively ousted Pavel Durov from the helm of VKontakte, the popular Russian social network site he founded, in an effort to halt critical content about Russia’s operations in Ukraine.

“They put it under Kremlin control, but it didn’t help,” says Soldatov. “The content is generated by users, not by employees of the company.”

Around the same time, high-traffic bloggers were required to register with the government as media outlets, and the laws on so-called extremist content were strengthened, says Olga Khvostunova, a political analyst with the Institute of Modern Russia, a pro-democracy think tank based in New York.

“Internet and especially social media were recognized as the tools that dissenters used to rally against the government,” she says.

Unlike China, where an elaborate network of automated tools and human censors filter and scrub controversial content from the web, Russia takes a relatively low-tech approach to online censorship. It relies more on putting political pressure on website operators to filter objectionable content than on sophisticated algorithms, Soldatov says.

Intimidation, Rather Than Technology

“The Russian approach is still not very sophisticated,” he says. “It’s still mostly based on intimidation rather than technology.”

For foreign companies like Facebook and Twitter, the threat is, effectively, that they’ll be barred from the country. Russia’s parliament recently passed a law restricting virtual private networks, which will make it harder for Russian users to get around countrywide site filters. The Russian telecom regulator has the right to blacklist sites and order internet providers to restrict them, says Maxim Ananyev, a graduate student in political science at UCLA who has written about internet censorship.

“This agency can issue an order to the internet service provider, so that a particular address is blocked on the side of the provider,” he says. “So when you want to type a certain address from Russia, it just doesn’t work.”

Major international social networks aren’t totally defenseless, though. Russian regulators have recently threatened to block Facebook for violating a law requiring data on Russian citizens be stored in that country, but it’s unclear if they’ll actually follow through. Facebook and other foreign sites, like the messaging tool Telegram created by VKontakte founder Durov, are popular enough that banning them risks triggering more unrest.

“If they block Facebook, this fact itself can trigger widespread protests,” says Ananyev. But whether Facebook or other companies will allow knowledge about the Russian government exploiting their platforms to change how they respond to Russian censorship requests remains to be seen—and may depend as much on perceived threats to their bottom line as on political principles.

“Facebook and Twitter do not have it as part of their mission to defend Western democracy,” says Giles.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(29)