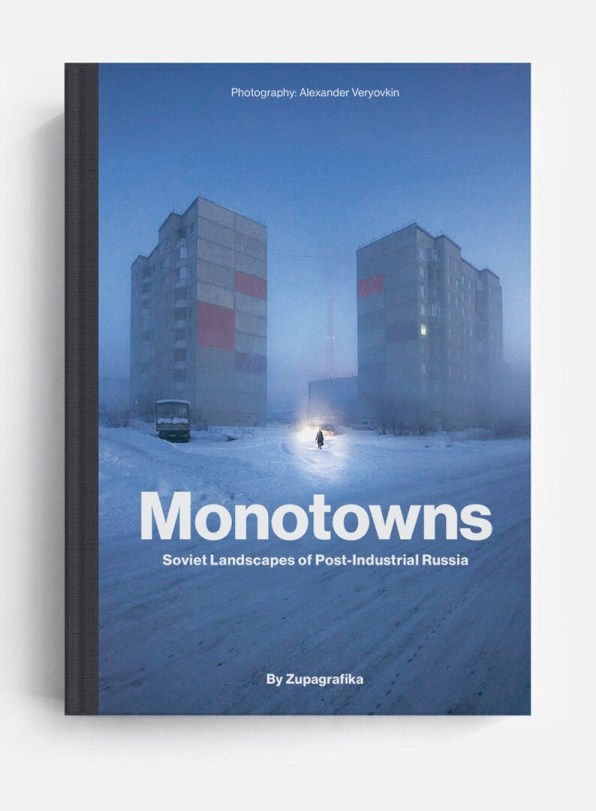

See the stark beauty of the Soviet Union’s abandoned company towns

Built on the perimeter of an open pit mine or on the permafrost fringes of a massive car factory, the company towns of the former Soviet Union are urban developments of economic extremes. With Brutalist concrete buildings tinted by fading pastel paint and no shortage of monuments to Vladimir Lenin, these towns burst out from the snowy tundra of Russia’s far north, forming vast and improbable urban agglomerations near and within the frigid Arctic Circle.

While they were created in the mid-20th century under the governance of the Soviet Union, and times have certainly changed, many of these cities are still occupied, and some of them are still functioning as single-industry company towns. Monotowns: Soviet Landscapes of Post-Industrial Russia, a new book from Zupagrafika, offers a glimpse at what these towns look like today.

Zupagrafika is an independent publisher and graphic design studio run by David Navarro and Martyna Sobecka, based in Poland. Previous books include explorations of the concrete buildings of the former Soviet Union and the architecture of Siberia, as well as an ongoing series of cut-and-fold paper model kits of Brutalist buildings.

Here, Navarro and Sobecka explain what these monotowns are like, how they’ve evolved since the end of the Soviet Union, and why they chose to photograph them only in the winter.

Fast Company: Company towns are notoriously precarious places, dependent on their main industry for survival. How are they designed and built differently from other, more economically diverse cities? And how do they differ from one another?

David Navarro and Martyna Sobecka: Soviet monotowns are urban settlements erected around single industries in the hinterlands of the former USSR—some thriving, others struggling to survive, still others partially abandoned. Although Vorkuta, Norilsk, Mirny, Kirovsk, Tolyatti, Cherepovets, Magnitogorsk, Monchegorsk, and Nikel might all be classified as monotowns, they differ as much as other cities. A key difference is their founding companies, i.e., the single economies around which they were built. They range from nickel or diamond mines, like in Norilsk and Mirny, to car manufacturing plants, as in Tolyatti. Their urban landscape also varies considerably.

As many monotowns have been erected in very difficult topographical locations, their architecture needed to be adjusted to the local challenges. Therefore, in Norilsk and Mirny you will find houses built on concrete piles to protect from melting permafrost and rows of panel blocks shielding the inner cities from the biting wind, almost like a medieval fortress. The housing estates in Norilsk are painted pink, green, orange, and blue, and their bright colors contrasting with the omnipresent whiteness immediately attract your attention and help children identify their homes during long polar nights.

FC: These towns were built under the Soviet Union. How have they changed since then?

DN and MS: The privatization that came after the fall of the Soviet Union has definitely taken its toll on the majority of state-owned enterprises, therefore, putting all monotowns in danger. Tolyatti or Mirny, whose economies remained dependent on one enterprise, are now managed by a private company. Other monotowns opted for diversification of their economy, like Kirovsk, which in recent years has become a thriving ski resort, taking advantage of its picturesque location in the Khibiny mountains. Not all monotowns have adapted to the post-1992 reality so well. The last nickel smelter in Nikel closed down in December 2020 and the city’s future is now being decided. Probably the most blatant example of a monotown that did not make it is Vorkuta, whose satellite settlements depopulate year by year, leaving ghost-town landscapes behind, as you can see in the book.

FC: The book features more than 130 photographs, all shot by Alexander Veryovkin. What was the process of working with him? How did you decide what to shoot and where to go?

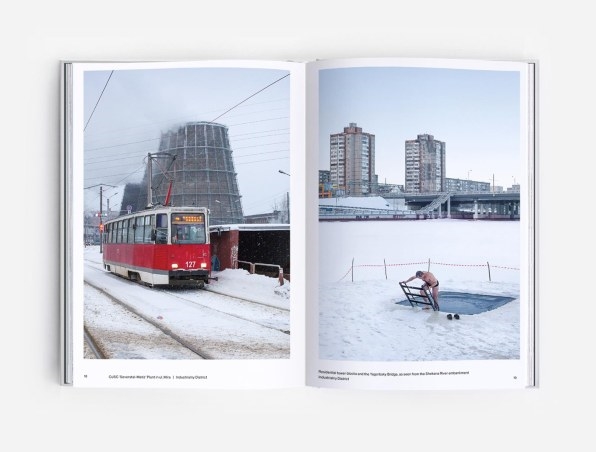

DN and MS: We have worked with Alexander for a few years now; he’s a fantastic photographer and we both already know how we work pretty well. Nevertheless, he still continues to surprise us with the amazing results of his work. We (Zupagrafika) first develop a concept for a book, then do the research into the locations and architectural objects that we would like to have in the book. Then we provide Alexander with a selection of spots and basic guidelines for shooting, like avoiding the sun, for example. Some new locations are also added by Alexander during shooting.

He worked in pretty extreme weather conditions. This is how Alexander describes his experience: “The coldest city while shooting for Monotowns was Vorkuta. The pictures were taken over a two-year period during wintertime, with temperatures reaching -35 degrees Celsius in some locations. Sometimes the camera would freeze to my face. I was very impressed with Vorkuta. I have not seen anything like this elsewhere. The city still has a lot of Soviet legacy, in shop signs, architecture, etc. I was also surprised by the number of abandoned houses. People are leaving, as there is no need to mine as much coal as before. Several ghost towns have already formed around Vorkuta, and in the city itself, the houses are the cheapest in the country.”

[Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

FC: All the photos were taken during winter. Why?

DN and MS: We have been documenting the postwar modernist architecture both in the form of illustrations and with a photo camera for a decade now. From the first shots back when we started, it became very clear to us that we didn’t like the results when the sun was out. The kind of contrast between the light and shadows, the color that the sun was giving to the concrete was something that we started to learn to avoid. Winter offers high chances of cloudy days in general, and is also a time where we would usually choose to travel. On top of that, snow makes the light more neutral and homogeneous, focusing the photos on the key elements we like to feature in our work: the architecture and the people.

FC: There’s a tendency, in the West at least, to think of this kind of Soviet architecture as bleak, or perhaps even lifeless. How do you see these buildings and towns?

DN and MS: We live and work in Poland, therefore, the architecture of the socialist era is still present in our everyday life. Martyna was born in the mid-1980s, and like many folks from this generation was raised in a Wielka Plyta estate, or blocks of prefabricated flats. You can see many different examples of this kind of prefab construction in our books.

Also, we need to remember that the uniformity of those buildings is only seeming. If you have a closer look, the towns, districts, and panel blocks vary in many ways as shown in our books Eastern Blocks or Concrete Siberia. The people who inhabit those buildings also apply all kinds of customized alterations to enhance their functionality. At the end of the day, the postwar estates, districts, and “microrayons” or microdistricts are designed for the people, with lots of greenery around, large playgrounds, and good communication with the inner cities. Mostly.

[Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

Mirny pit shaft [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

Kukisvumchorr Mountain prefab panel houses [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

Soviet mosaic inside the ‘Olymp’ swimming pool in Tolyatti. [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

[Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

The Volgar Sports Palace in Tolyatti [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

Uninhabited frozen panel block in Vorgashor, Vorkuta. [Photo: Alexander Veryovkin for Zupagrafika/©Zupagrafika]

(35)