Terrorism Is No Game, But Playing This One Could Help In The Fight

Sean Captain November 17, 2016

Pilots practice in flight simulators, med students use VR to visualize surgeries, and government officials concerned with organized crime and terrorism play an online game created by the U.S. military called CounterNet. It’s not a shoot ’em up like Call of Duty or the government’s own America’s Army: Proving Grounds. Rather, CounterNet focuses on “the left side of the boom,” as project leader Ryan McAlinden calls it: The planning and organizing that takes place before an attack and, increasingly, online.

Don’t think of the CIA master control room in the movie Jason Bourne or things the NSA can do. CounterNet features Twitter, Vine, Instagram, YouTube, PayPal, and other common online networks, simulated for a cat-and-mouse game with a mysterious group of terrorists. Or are they peaceful protesters? Players have to figure it out.

“CounterNet is focused very much on the ways in which groups and individuals use the Internet for . . . nefarious, criminal, terrorist purposes,” says McAlinden, the director for modeling, simulation, training at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies. ICT is what’s known as a military-sponsored, university-affiliated research center, and CounterNet was set up in May 2015 with funding from the Naval Postgraduate School. It’s used in a training program for military and intelligence officers from around the world at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Germany. While there are many fears about nefarious dealings on the encrypted Dark Net, public social networks are key venues for crime. Since June 2015, Twitter has suspended 360,000 accounts for links to terrorism.

According to McAlinden, despite the point-and-click simplicity of online networks, there’s a perception in the intelligence community in many countries that using them for information gathering is beyond the range of non-techy “policy folks.” He adds, “I think the stigma is, well, policy people aren’t smart enough to know the way that these people use the internet. That’s where this originates from, which is true to some extent.”

CounterNet‘s job is to make the “policy folks” smarter through trial and error in a 10-level game dedicated to themes such as propaganda, financing, and tracking. “It drew heavily on our experiences with choose-your-own-adventure books,” says McAlinden, who, like his colleagues, grew up in the analog era of interactivity. “We had heard the way that some of these criminal groups were using the internet,” he says. “They would have to make a decision [to] do A, B, C, or D. And depending on what option they took, it would head them down different paths.”

Trust Nothing

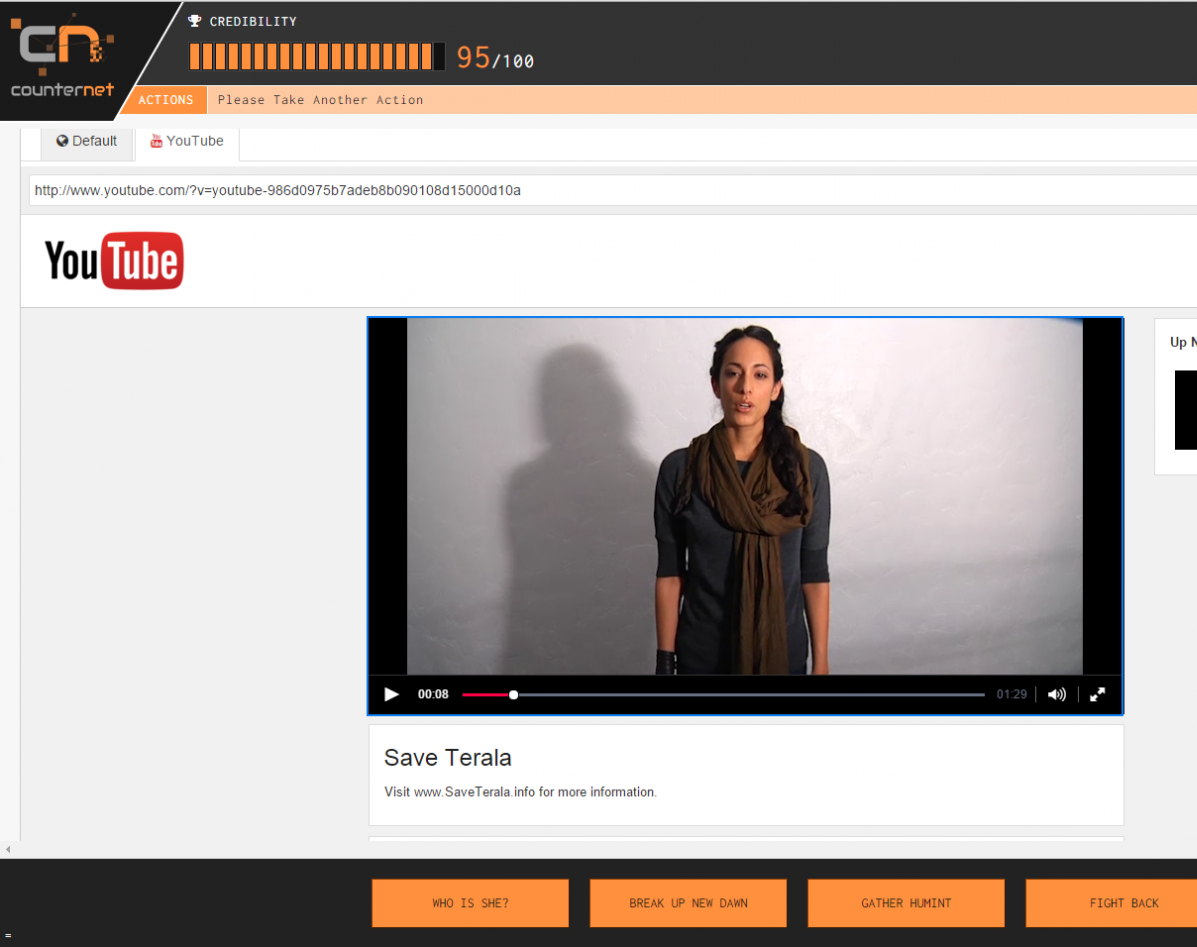

CounterNet starts with a (faux) YouTube video featuring a dark-haired woman who goes by the name Subala and represents a group called EcoTerala. She’s rallying support against a dam that she says will divert water to resorts and luxury export agriculture, and away from the towns and small farms in the fictitious country of Terala. (The plot is inspired by a real water dispute between India and Bangladesh.)

“This is what will happen to our beloved Terala if we don’t take action,” she says, showing dried-up lands and quoting stats about the global water crisis from the World Bank and the U.N.—hardly revolutionary hotbeds. “New Dawn has come together from every part of our society—students, villagers, families, workers, businesspeople, to say to those that are stealing our water, ‘Enough! This stops now!'” Then she announces an upcoming rally at a dry lakebed.

The game was authored by a screenwriter, USC film professor Richard Kletter. He wrote The Black Stallion Returns and a bunch of TV movies, including Cyber Seduction: His Secret Life. (Kletter’s son had worked on efforts to resolve the India-Bangladesh dispute.)

The player’s task is to find out who Subala, EcoTerala, and New Dawn Terala are, what they want, and what—if anything—to do about them. Each level of the game has five strategy categories, such as “Build your Team,” each with three actions like “Create digital response team,” “Work with environmental organizations,” and “Send people to the rally.” After clicking the second option, I saw in an email that the environmental groups haven’t heard of EcoTerala or New Dawn. The agents who went to the rally got some names. I also saw an Instagram and Vine clip of Subala at the protest.

I learned in a later level that we already had a dossier on Subala, so I requested it. I also gathered intel on the people behind fictitious Twitter handles like @thecherub and @takeaction. (Fun facts: There is a real @thecherub who has under a dozen tweets and followers; the real @takeaction belongs to an online-rights advocacy program run by Google.)

Taking steps that are too bold or too timid can be dangerous. McAlinden points out that some choices are just “outright incorrect,” while others won’t necessarily hurt or help your mission.

Many of the no-nos seemed obvious. I knew not to “Take down EcoTerala” on level 1 or “Use infiltrators to provoke a violent response.” Likewise, I’d be naive to choose, “Not every protester is a terrorist. Leave them alone.” Clicking it anyway, I got a pop-up saying that I can’t fight back if I don’t track them, and announcing that I’d lost five of my starting 100 credibility points.

I was surprised by some things the game rates as mistakes. I proudly clicked on, “Don’t violate privacy laws,” then lost points and had to repeat the level. I earned points, though, when I planted stories in the media.

Who The Players Are

About 1,000 people have been through the CounterNet program, says McAlinden. They come from various parts of government, such as interior and justice departments or ministries, emergency response, or law enforcement. They come from several countries from Eastern Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Central and South America.

Why are all these countries learning how to deal with ecoterrorists? With everything happening in the world, are they such a concern? No, says McAlinden—which is why they were the perfect choice. “When we put together the scenario topics, if we did something that was ISIS-aligned or about drug-trafficking in Central America . . . then people would nitpick it to death,” he says. “The Turks will say, ‘Well, you know, ISIL [ISIS] doesn’t use [a particular online network] for this, or human traffickers don’t use it for that.'” Because government officials are less focused on ecoterrorism, they won’t get hung up on verisimilitude.

In fact, terrorism isn’t always the top concern. “When they attend this course, [the trainers] will ask the people, ‘Why are you here?'” McAlinden says. “A lot of Central and South Americans are like, ‘Narco.’ A lot of Asian and Eastern European ones will say human trafficking. With Africa, it’s criminal corruption, trying to undermine the state or federal system using money or bribes or whatever.”

CounterNet isn’t an open world. I didn’t compose my own tweets or emails, for instance. It doesn’t have the AI for that. Rather, I clicked on options that sent pre-scripted text and got pre-scripted answers. The game is just an introduction to the online world. Expecting players to figure out every single inner working would be too much. CounterNet does expose them to the confusion and ambiguity of the internet, like this fictional exchange on simulated Twitter about Subala’s origins:

@notinmyhouse She grew up in a village outside Jenbe. Put herself through University. Worked 2 jobs as a maid in a hotel.

#saveterala

@Greenworld Nice story. How do you know it’s true? I heard she’s been arrested for drugs and multiple robberies.

In another exchange, a jokester asked if Subala is single. Real-life social media is messy and often seems silly. But it’s not all innocent, and even the most innocuous-looking tweet needs to be taken seriously.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(31)