The Main Argument For Rolling Back Net Neutrality Is Pretty Shaky

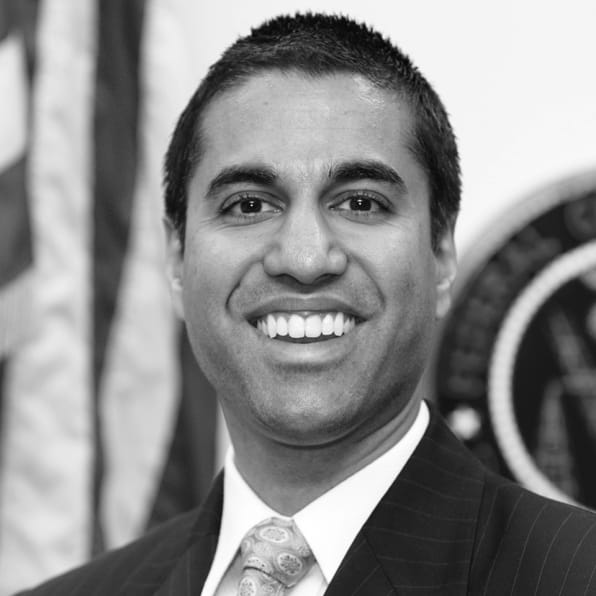

FCC chairman Ajit Pai’s central argument for eliminating net neutrality rules, which he introduced this week with a plan to “reverse the mistake” of the Obama-era regulations, is that doing so will fire up investment in broadband networks. But that prediction is very optimistic, say experts who warn that his proposal could very well do little or nothing to stimulate such investment.

Back in 2015, the Democratic-controlled FCC reclassified broadband as a Title II communication service to be regulated like a public utility. The new rules prevented big ISPs like Verizon and Comcast from throttling the speed of sites and apps and setting up paid fast lanes.

Pai’s central argument is that those net neutrality rules had the immediate effect of slowing down investment in broadband networks. He said the internet was already working fine before the FCC stepped in to impose unnecessary regulations for purely political reasons.

According to backgrounder sent out from Pai’s office, the 12 largest U.S. ISPs spent 5.6% (or $ 3.6 billion) less on building out their broadband networks during the first two years of the Title II era. (The statistic lacks a citation.)

It’s true that ISPs desperately want to extract more “value” from the networks they operate. They detest the idea of operating a neutral “dumb pipe,” and detest the idea that the government is regulating them into that role. They want to be able to offer fast lanes to internet companies like Netflix, many of which, by the way, are willing to pay. ISPs want to sell zero-rated services where certain websites or services are carved out and delivered with no data charges. When prevented from monetizing the network to the fullest, as they see it, they’re naturally a little less excited about building on to their networks.

But Pai lays the entire blame for the investment slowdown at the feet of the previous FCC that passed the 2015 Open Internet Order, and that’s where his argument starts to sound like a political one.

“While investment in broadband infrastructure has certainly dwindled in recent years, the impact that net neutrality regulation has had is very much open to debate,” says Dan Hays, global tech, media, and telecom lead at PwC’s Strategy& group.

“In fact, it’s quite plausible that growth in market penetration of broadband services, coupled with acceleration of industry consolidation over the past few years, have more to do with reduced spending, despite the pleas of network operators,” Hays says. The subtext here is that investors in telecom companies, as a rule, detest massive new capital expenditure spending on network infrastructure. Combining with other networks is one way to avoid doing so.

Pai said the real losers are poor and rural Americans who have to live with slow or no internet service at all, because the smaller competitive carriers that might serve them are disincentivized from building out their networks. Pai believes the return of broadband to Title I and a lighter regulatory touch will result in more infrastructure investment, more jobs, and better broadband.

PwC’s Hays points out that doing away with network neutrality rules is a change that would apply to the whole ISP industry, and might not have the hoped-for effects. In fact, Hays says, it’s more likely that it wouldn’t have those effects.

“Even if rolling back net neutrality regulations does spark an increase in network investments, the questions will be ‘how much’ and ‘where,’” Hays says. “Deregulation is unlikely to solve the fundamental economics problem of deploying broadband networks in rural and low-income areas of the United States.”

Pai’s rollback of net neutrality guarantees might help one industry (big ISPs) but hurt another (internet companies). Having to pay for “internet fast lanes” might dramatically change the economics of selling an internet service.

“Although network investments could increase . . . internet companies providing over-the-top services—particularly the vibrant startup economy that the country has prized—could well be at risk,” Hays says.

Carriage charges might begin ratcheting up until smaller companies can’t afford to pay. So broadband service might get better and become more available, but the diversity of content consumers can access using it might diminish. And yes, content is king, not the pipe used to grab it.

Pai and the FCC has now opened the new proposal to roll back net neutrality protections to public comment. The commission will vote on the proposal in May.

Meanwhile, Congress is watching closely, and some members believe that Congressional action to settle the matter once and for all might be the best way forward.

And finally, even if Pai can push his proposal through the commission, a raft of internet companies, and tech and free speech advocacy groups will be waiting in line to say “See you in court, Ajit.”

(37)