The Music Industry’s New War Is About So Much More Than Copyright

Taylor Swift has “declared war” on YouTube. Or at least that’s how some have characterized the open letter signed by Swift, U2, and around 180 other artists last month, calling on lawmakers to reform the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, or DMCA.

The DMCA, says the letter, “is broken and no longer works for creators.” The letter takes aim specifically at Section 512 of the law, which gives user-generated content platforms “safe harbor” from liabilities related to copyright infringement. In other words, artists say, YouTube profits off pirated copies of their music. That directly diminishes songwriters’ and artists’ earnings while allowing “major tech companies to grow and generate huge profits by creating ease of use for consumers to carry almost every recorded song in history in their pocket via a smartphone.” YouTube, Google, and Alphabet aren’t mentioned by name, but it’s obvious which “major tech companies” they’re talking about.

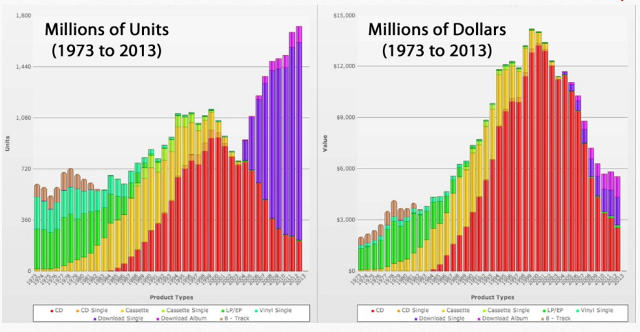

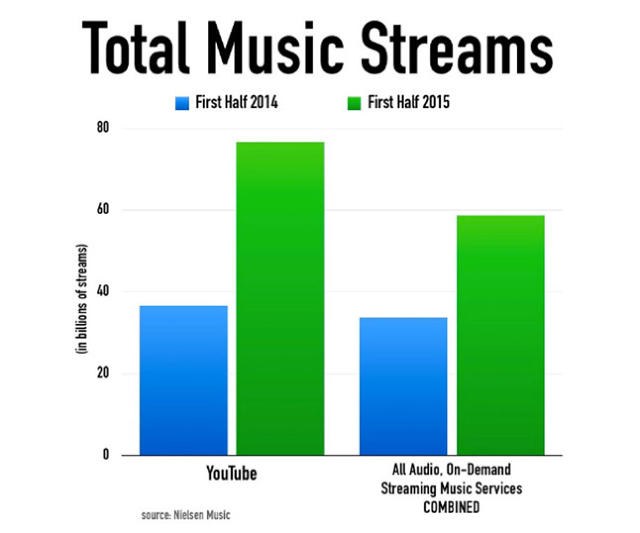

While global music consumption is at an all-time high—and YouTube is the number one source of music streams, boasting more listeners than Spotify and Apple Music combined—only a small amount of the revenue generated by that consumption is passed along to artists and musicians, according to the letter. (You can read it in full here.) The artists’ share is allegedly dwarfed by the “huge profits” earned by the platform. According to the Recording Industry Association of America, YouTube saw a more than 100% increase in the number of video plays last year, while revenue sent to U.S. artists only saw a 17% increase.

“They feel they are being shortchanged,” Mark Mulligan, managing director of Midia Research, a boutique media and technology analysis company, told the Guardian.

MORE LISTENING, LESS REVENUE

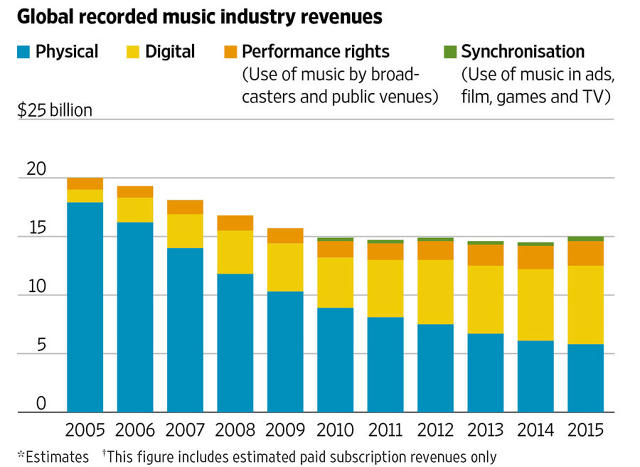

STREAMING ACCOUNTS FOR MORE MUSIC INDUSTRY REVENUE THAN EVER

The Issue Of Piracy

The music industry has long claimed that YouTube is not nearly as effective as it claims to be at identifying copyright-infringing videos uploaded by fans or other third parties. The DMCA’s “Safe Harbor” provision protects the platform from prosecution if one of its users posts infringing material, provided that the site was unaware of the infringement. (These protections were crucial for the growth of social networks where the majority of what is posted there is submitted by users, unvetted; Without the provision, sites like Twitter and Facebook would have likely been litigated into bankruptcy and oblivion.). In turn, if a copyright owner or her representative reports an example of copyright infringement, the site must take steps to remove the offending material, or the site can be held legally responsible.

Taylor Swift can rely on a team of lawyers, but for most artists, searching for pirated versions of their songs on YouTube is an onerous task. To help police the platform for pirated music and videos, YouTube’s automated Content ID system alerts rights owners when their copyrighted material is found on the site, giving them the opportunity to either take the offending piece of material off the site or to monetize it with ads and collect the revenues.

“The overwhelming majority of labels and publishers have licensing agreements in place with YouTube to leave fan videos up on the platform and earn revenue from them,” a YouTube spokesperson said last month in a statement. “Today the revenue from fan-uploaded content accounts for roughly 50% of the music industry’s YouTube revenue. Any assertion that this content is largely unlicensed is false.” Since YouTube launched Content ID a decade ago, the program has paid $2 billion to artists and labels, the company says.

YouTube claims that its Content ID system catches copyright violations 99.7% of the time. The labels say otherwise: Some record executives claim that YouTube’s success rate is only 50%, according to the Wall Street Journal, implying that there’s a lot of copyrighted material on YouTube for which the proper rights holders aren’t receiving compensation. A Sony executive told the outlet that since 2012 the label had discovered 1.5 million copyright violations that Content ID had missed, amounting to $7.7 million in lost revenue.

However, according to Midia, the impact of these “Safe Harbor” streams are small, with just 2% of music video views coming from rights-infringing user-generated uploads. Three-quarters of all music video views are official, says Midia, and of those, three-quarters come from Vevo, a joint venture between Google, Sony, and Universal Music Group.

Whatever the true numbers are, the artists say they want Congress to change the DMCA so YouTube is held liable and responsible for any copyright infringements, and not just the ones identified by the music labels or the platform’s Content ID system. That could prove devastating to the platform. So too could a decision by the music industry to move Vevo to another platform, like Facebook—what Mulligan of Midia calls a “nuclear option.”

But there’s another way YouTube might be able to cool this war, and it has little to do with piracy.

This Isn’t Just About Piracy And Copyright Reform—It’s About Declining Royalties

Rampant piracy is the narrative being pushed by the music industry in its letter to Congress, but the truth is more complicated. Read between the lines of the letter, and a larger, more lucrative and familiar problem appears: The royalties that an artist or songwriter gets each time a stream of their song is played are declining.

Putting piracy aside, legal streams earn much less on YouTube than they do on Spotify or Apple Music. It comes down to a core issue with YouTube’s business model—one that DMCA reform will not resolve.

YOUTUBE’S AD-BASED ROYALTIES ARE A FRACTION OF SUBSCRIBER ROYALTIES

Artists reap revenues made from ads shown before and alongside a video, but those revenues appear to be decreasing. In 2015, YouTube paid $740 million to music rights holders—a 15% increase year-on-year, according to Midia’s research. But at the same time, streams on YouTube and Vevo grew a whopping 132% to a record 751 billion plays.

This surge in plays cut YouTube’s effective payment rate per stream to rights holders in half, from $0.002 in 2014 to $0.001 in 2015, according to Midia, based on data from the record industry and YouTube announcements. That drop in payout rates amounted to a loss to the record industry of $755 million, Midia estimates. (YouTube does not disclose yearly ad revenue payments, although a person “close to the company” told the Financial Times that the $740 million figure for 2015 is “understated.”)

THE RISE IN AD-SUPPORTED STREAMS

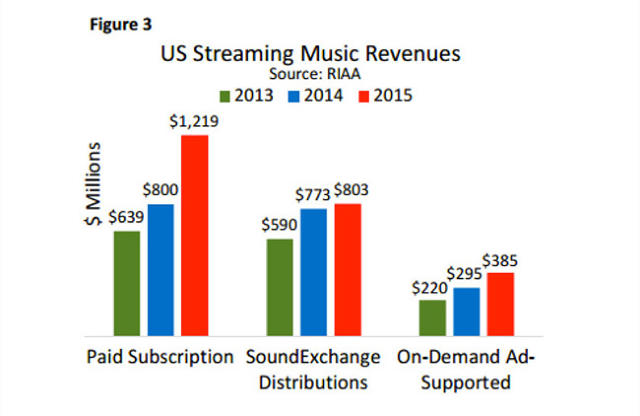

AD-SUPPORTED STREAMS VS. SUBSCRIPTION-SERVICE STREAMS IN U.S.

Zeroing in on the U.S. market, in 2015 the royalties artists earned in the U.S. from “On-Demand Ad-Supported Streaming”—that includes all the cash YouTube sent to artists and labels last year, plus revenue created by Spotify’s free tier—amounted to only $385 million, reported the Recording Industry Association of America. That was a 30% improvement on the $295 million the industry earned from ad-based streams in 2014, it said. But during that same period, again, the growth of music streaming on YouTube far outpaced revenue growth.

By comparison, the revenue created by paid subscriptions—like Spotify’s and Apple Music’s—was $1.2 billion, says the record industry, or over 3 times the amount created by YouTube. Nor do YouTube’s royalties match the $803 million the music industry earned from online radio listening on smaller platforms like Pandora, labeled above as “SoundExchange Distributions.”

THE RISE IN STREAMING SUBSCRIBERS

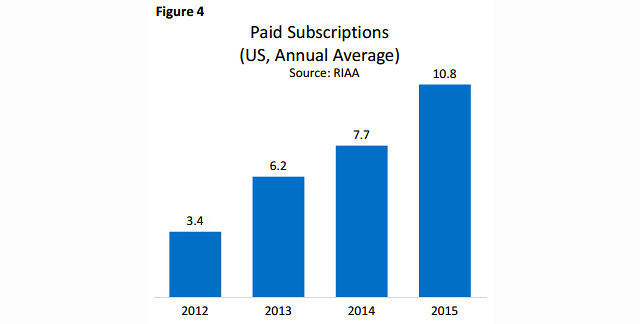

The magnitude of this disparity—a roughly $800 million gap between ad-based royalties and subscription-based royalties, according to the RIAA—really comes into focus when you consider that in 2015 the industry estimated that there were only 10.8 million paying streaming listeners in the U.S. YouTube, on the other hand, has an estimated 200 million users in the U.S. That means each paying streaming U.S. listener creates over $120 a year—or the annual price of a $10 a month subscription—while each YouTube or free Spotify listener in the U.S. nets less than $2 a year.

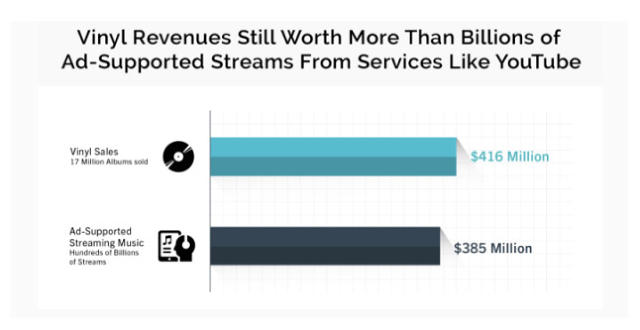

And here’s one final way to look at YouTube’s dismal royalties in the US: last year, the platform earned less for artists than sales of vinyl records did.

EARNINGS FROM VINYL VS. ROYALTIES FROM AD-SUPPORTED STREAMS

COPYRIGHT REFORM: A WAY TO GAIN LEVERAGE IN ROYALTY NEGOTIATIONS?

Ultimately, the amount of lost revenue due to copyright violations that YouTube’s automated system has missed still pales in comparison to the billion-plus dollars that the music industry earns each year from YouTube’s subscription-based competitors like Spotify and Apple Music.

In other words, DMCA reform alone—getting stricter on piracy and funneling more users to officially sanctioned, ad-supported uploads—won’t calm complaints by artists or the record companies that YouTube is stiffing them in ways its subscription-focused competitors are not.

What might help however is a change in how ads work on YouTube, and how they make money for artists and labels. One issue at play: Ad sales tend to be lower in developing markets, where YouTube’s growth is happening fastest. Currently, 80% of YouTube’s audience is said to live outside the U.S. Those may be valuable new listeners in the long run, but for now they’re bringing a fraction of the earnings they used to.

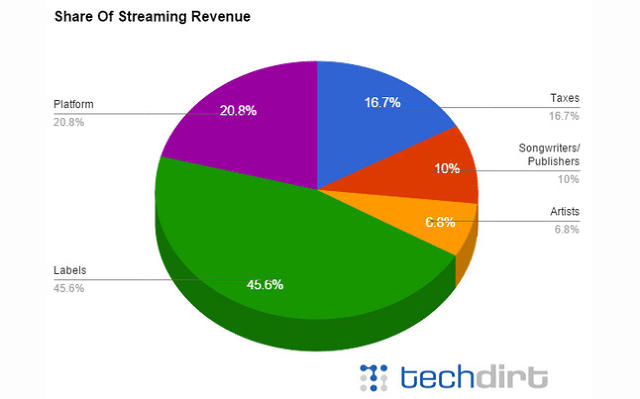

Indeed, all three major labels are currently in contract renewal negotiations with YouTube over the royalties it pays per play; Universal’s contract, sources say, has already expired. Also, it’s worth noting that while the music industry has made beloved performers like Taylor Swift and Bono the faces of this fight in order to curry favor with their fan bases, negotiating better contracts—while great news for major labels—may not fix most artists’ revenue woes. That’s because labels often take home the lion’s share of the revenue created by music consumption, just as they have throughout the history of recorded music.

WHO EARNS WHAT FROM STREAMING

Some observers have argued that the music industry is using the copyright battle as nothing more than a way to gain leverage over YouTube. After all, if the DMCA were reformed like the artists’ letter suggests, it could bog YouTube down in an endless river of copyright infringement suits.

But it could also threaten to decimate the chances of smaller content platforms from ever growing to the size of what Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are today, which would be bad for competition. Moreover, by making the DMCA more strict, it could severely damage how issues of Fair Use are handled on the web. Video artists and musicians whose work relies on fairly appropriating copyrighted work to create something new or to comment on the source material, may wake up one day to find all their work deleted from YouTube’s servers, sent off into digital oblivion.

As the industry and the business models continue to evolve—and as YouTube expects artists to be patient that on-demand content will someday be better-supported by advertising—artists and the music business are grabbing whatever leverage they can.

Will YouTube Red, Its Subscription Service, Help The Situation For Artists?

In October, Alphabet launched YouTube Red, and for 10 bucks a month—the same price as Spotify—users get unlimited access to ad-free videos and exclusive content. The opportunities for revenue creation with YouTube Red are clear: The Verge’s Ben Popper suggested that “if just 5% of [YouTube’s] U.S. viewers were to sign up for the service, it would add more than a billion dollars in annual revenue to the company’s bottom line.” This means more money for the music industry too: Speaking to the Financial Times, YouTube’s chief business officer Robert Kyncl calls Red “another revenue source for rights holders.”

But just how significant a revenue source Red will be remains to be seen. Much of the planned exclusive content is not music-related; rather, with a programming slate that includes participation from major TV networks and non-music “YouTube stars” like PewDiePie, YouTube Red seems to be positioning itself less as a competitor to Apple Music and Spotify’s paid tier and more like one of the many VOD platforms out there, like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video—which wouldn’t necessarily improve the fortunes of artists.

Still, YouTube is trying hard to funnel music lovers to Red through its YouTube Music app, which, thanks to an aggressive marketing campaign, briefly unseated Pokémon Go last week to become the top-downloaded free app on the iTunes chart. New users will receive a two-week free trial to Red. But there may be little incentive for those free users to stick around and start paying because, unlike Spotify and Apple, which offer significantly less to free mobile users versus paid ones, YouTube Music with a Red subscription offers virtually the same music experience, only without ads.

Moreover, according to conversations with those familiar with the matter, in spite of its efforts with YouTube Red, the company expects free, ad-supported streaming to remain core to its business. The fact that ads aren’t yet a wildly lucrative source of revenue is a matter of patience: As more ad inventory moves from television and terrestrial radio to digital platforms, YouTube predicts that the revenue from free ad-supported streaming will increase in time. And when you’re owned by one of the most valuable companies in the world, it’s easier to be patient with sluggish revenues.

In its defense of ads, YouTube has argued that ad-based music has worked for radio. But there’s a key difference between YouTube and radio: Radio controls what listeners hear, making it great free promotion for the artist. On-demand services like Spotify and YouTube—on which users search for what they want to hear, hit play, and voila, it’s there—don’t offer the same promotional benefits or capture the same kind of attention.

In short, artists and the music industry writ large have a reason to be feel “shortchanged” by YouTube. Unfortunately, YouTube may not be able to meet their demands without dramatically rethinking its business model, and the notion that music can be supported by just ads.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(27)