The Senate infrastructure bill includes $1 billion to address devastation caused by freeways. Experts say it’s not enough

The $1 trillion infrastructure bill passed by the Senate aims to build a lot. It also hopes to tear some stuff down.

Included in the bill’s 2,000-plus pages is a plan for a pilot program to demolish urban freeways.

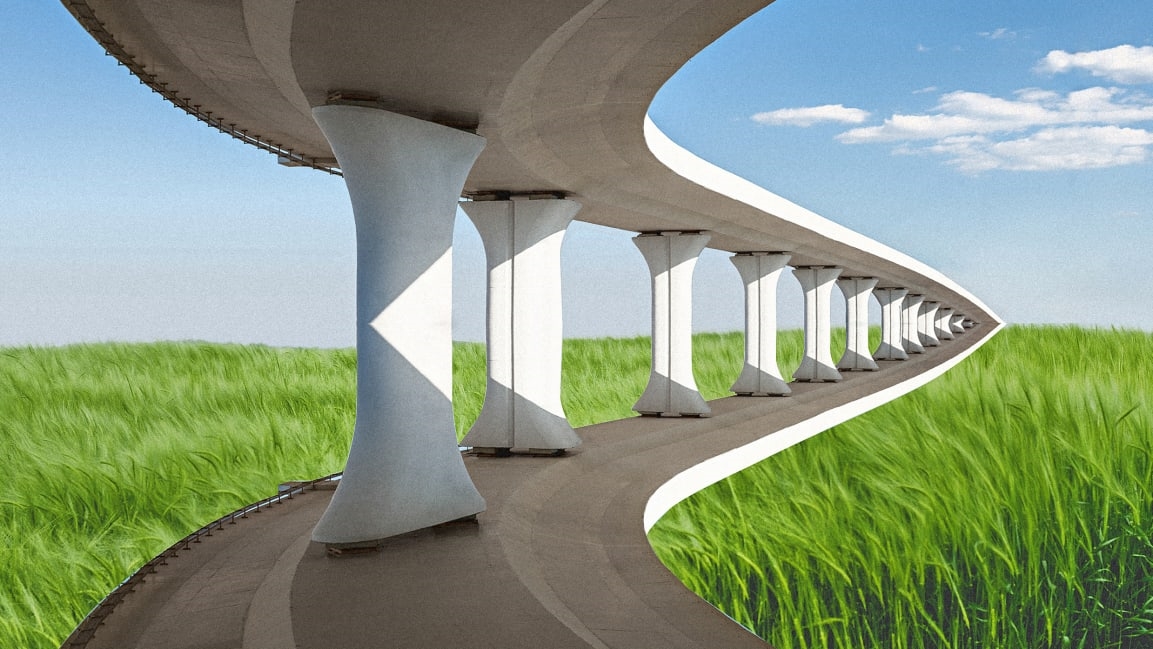

The program would target urban freeway projects that, either through happenstance or malice, destroyed neighborhoods and divided communities from the 1950s onward. With $1 billion set aside for the task, the bill could create a high profile catalyst for rethinking freeways in cities.

“It represents a new kind of program and something that hasn’t been part of the federal infrastructure policy framework before,” says Robert Puentes, president and CEO of the Eno Center for Transportation, a Washington D.C. transportation policy center. “It makes the concept of freeway removal real for places that may not have been thinking about it, places that may realize this is now an option for them. All of these nudges in the right direction from the federal government are important.”

Named the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, its main goal is technically not only the demolition of freeways but rebuilding the neighborhoods they’ve affected. As described in the bill’s text, the program focuses on efforts to either remove or retrofit freeways in order to reduce physical barriers that blocked economic opportunities, doomed minority owned businesses, and demolished thousands of homes in communities of color. The program would fund feasibility studies on the impacts of removing, retrofitting, or mitigating freeways that have cut communities apart, and begin planning those efforts. For removal plans already in the works, the bill could also provide the first dollars to actually begin tearing the roads down. The bill lists no specific freeways, but among those targeted by activists and planners are freeways in Rochester, Flint, Baltimore and Dallas.

Priority would be given to economically disadvantaged communities, which were historically most affected by the construction of freeways in the mid-century era of urban renewal. Often framed as beneficial modernization projects for cities, urban freeway construction was also used by some officials to disenfranchise or even completely erase minority neighborhoods. Freeway construction in Tulsa demolished more than 100 Black-owned homes and businesses. In Detroit, freeway construction and urban renewal destroyed more than 350 Black-owned businesses and likely thousands of homes. “It was considered a two-fer, that the central business district was getting an interstate, but also being able to eliminate what at the time was called substandard housing, which meant minority neighborhoods,” says Ted Shelton, a professor of architecture at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who has studied the disproportionate impacts of highway construction in American cities. “That was an unrecognized history for a very long time.”

He says the infrastructure bill’s freeway removal program could have positive effects in places that have spent decades dealing with barriers that have limited physical access to jobs and services, and the environmental hazards that put freeway-adjacent communities at higher risk for asthma. “Some of the neighborhoods have persisted in a shattered form. For those neighborhoods it could be significant, but they’ll never be what they would have been,” says Shelton. For others, it’s already too late. “Some of these neighborhoods were obliterated,” he says.

Freeway-divided neighborhoods exist in many cities. The White House’s summary of the bill highlights two notorious examples: the Claiborne Expressway, which was run through a largely Black neighborhood in New Orleans, and the elevated Interstate 81, which slices across the center of Syracuse, New York.

But these are just the start. Dozens of urban freeways around the country have caused the problems this removal program hopes to address, and activists, urban planners, and even some government officials have been calling – in some cases, for decades – for their removal. Former U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx made a notable acknowledgement of the problem in 2016 when he spoke out about how a freeway had physically isolated the largely Black neighborhood in Charlotte where he grew up. “My neighborhood had one way in and one way out, and that was a choice,” he told Governing Magazine in 2016.

The latest edition of the Congress for New Urbanism’s Freeways Without Futures report highlights 15 projects that it says are primed for a transformation, including Interstate 244 in Tulsa, Interstate 5 in Seattle, and Interstate 980 in Oakland.

Transformation may be an appropriate word for what the infrastructure bill’s program can do. In most cases, the program is not simply bringing in the wrecking ball. Some divisive freeways, particularly those dug into trenches, could possibly be capped with a reconnective lid, like the five acre Klyde Warren Park, which was built over a recessed eight-lane freeway in downtown Dallas. Others may be converted from multilane free-for-alls to slower, more controlled boulevards that are less of a barrier to pedestrians.

If the bill becomes law, planning grants of up to $2 million will be available to states, local governments, tribal governments, metropolitan planning organizations, and nonprofits. Construction grants will start at $5 million and go up from there. These projects aren’t cheap. In Dallas, the first phase of Klyde Warren Park cost $110 million, and was only possible because of $50 million in seed funding from private philanthropists.

For freeway removal activists, the $1 billion falls far short–especially when the program was initially proposed with a budget 20 times higher. A recent letter signed by 91 cities, transportation groups, and urban planning organizations bill blasted this reduction. Written by a group calling for the removal of Interstate 35 in Duluth, Minnesota, the letter argues that what’s on the table could barely cover the full costs of a single freeway capping or freeway-to-boulevard conversion project, let alone the dozens that are already in various stages of feasibility planning. The letter notes that even amid this push for freeway removal, the infrastructure bill also proposes a historic level of freeway building.

Puentes says the relatively modest level of funding can at least move the concept of freeway removal forward. “It is still a pilot program, and it is kind of the point of the pilot to figure out how much can you get done,” he says.

Shelton agrees that the $1 billion in funding doesn’t go far enough. “It’s undoubtedly a token,” he says. But he also argues that the fact that the program has even been proposed is a huge step forward. “The recognition that this is something that we ought to be thinking about on the federal level and recognizing it as a legacy of the urban portion of the interstate highway system is significant,” he says.

(37)