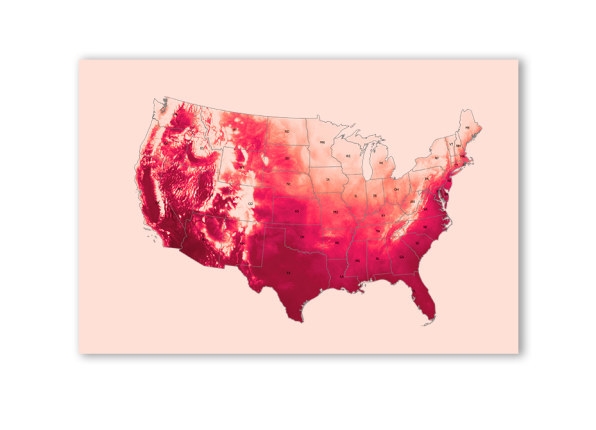

These maps show how many ‘dangerous’ heat days your neighborhood may have by midcentury

Right now, there are only a few pockets of the U.S. where it’s possible that the heat index might rise above 125 degrees Fahrenheit—a particularly dangerous threshold for human health. But by the middle of the century, a much larger area is at risk, sprawling from the Gulf Coast across a swath of the middle of the country, and reaching as far north as southern Wisconsin.

A new report maps out where it could happen, along with the increased risk of more ordinary (but still risky) extreme heat, heat waves, and temperatures that surge outside local norms. In a new tool, you can type in any American address, and see both the risks from heat in your neighborhood now and by midcentury. It’s part of Risk Factor, a broader climate risk tool that also shows the risk from flooding or wildfires for any American address.

[Image: courtesy First Street Foundation]

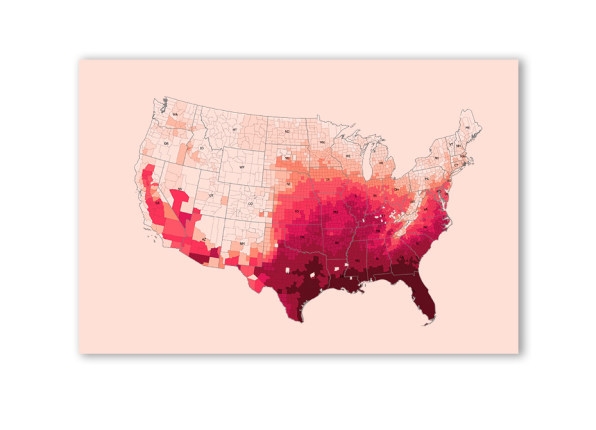

The researchers call the area at risk of the worst-case scenario the extreme heat belt. “Currently, there’s only about 50 counties that have any estimate of reaching 125-degree heat index in today’s environment,” says Jeremy Porter, the chief research officer at First Street Foundation, the nonprofit that created the tool. “But by 2053, that’s going to grow to about 1,000 counties . . . you go from having about 8 million people today with potential exposure to that level of heat to about 108 million in 30 years.”

[Image: courtesy First Street Foundation]

When it gets that hot, it’s dangerous to be outside. “A heat index of 125 is that level at which our body is effectively unable to cool itself over a prolonged period of time,” says Zachary Schlader, a professor at Indiana University School of Public Health, who studies the impact of heat on the human body. “What would happen is that the temperature on the inside of the body will just continue to rise, unless you were able to escape that environment.”

Of course, lower levels of heat can also be deadly for vulnerable people, or people who have to work outside. And it’s already very hot. The summer of 2022 has broken heat records across the U.S. In Salt Lake City, temperatures soared over 100 degrees on 18 days in July. Austin had 29 triple-digit days that month (and another 22 in May and June). Newark, New Jersey, has gone through four consecutive heat waves since late June. And cities like Boston, Denver, and Portland, Maine, have broken daily heat records.

But as climate change keeps making heat waves longer and more intense, this summer is also likely to be cooler than most you’ll experience in the rest of your lifetime. The tool shows both the current risks from heat in American cities, and how heat will increase in each location. “Heat ends up killing more people than any other [weather disaster],” Porter says. By one estimate, heat contributed to 1,577 deaths in the U.S. in 2021, but the number may be even higher; heat exacerbates other conditions, such as heart disease, and the link to heat often isn’t officially reported as the cause of death.

In the report, the research team looked at how many days each year each location has a heat index over 100 degrees. They also calculated how the number of these “dangerous days” will change by 2053, based on datasets from the federal government and others, combined with heat modeling. In Miami-Dade County, for example, there will be 41 additional triple-digit days each year by midcentury. The number of heat waves, with multiple days of extreme heat, will also increase.

The researchers also mapped out “local hot days,” or days above the local 98th percentile temperature. Someone living in a place where it’s usually cooler, such as Seattle, might start to see health impacts at a lower temperature than someone living in Phoenix who is more acclimated to heat (that person living in a historically cooler region is also less likely to have air-conditioning). Someone who’s planning to relocate might use the tool to reconsider. For each address, the report also calculates how much more someone is likely to spend on air-conditioning bills in the future. “Your energy bills are going to go a lot higher,” Porter says.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(31)