These San Francisco High School Students Are Recruiting Teachers To Resist Trump

Sixteen-year-old Brianna Carreno dreams of being a nurse one day, but for this daughter of a Latina hospitality worker, who grew up attending events at her mom’s union hall, career ambitions and political organizing are intimately intertwined. So when Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton last month, despite losing Carreno’s home state of California by about 30 percentage points, she knew she couldn’t just sit back and be silent about an election process that seemed to gloss over her needs.

“We’re just sick and tired of how older generations are trying to control the newer generation,” Carreno told a packed auditorium of over 100 teachers from around San Francisco, Alameda, and San Jose.

They traveled on a cold Thursday night last week to Leadership High School, a charter school in the city’s working-class Excelsior/Mission Terrace neighborhood, where Carreno and her classmates fear that Trump’s election victory will encourage a rise in racism that could crush their dreams. Social and political protests have long been the domain of university and college students, but here in San Francisco, it’s high-schoolers who are leading the movement against President-elect Trump—and they’re bringing teachers along with them.

“I’m resisting by showing them I’m going to continue my education by becoming someone, by becoming someone very successful,” Carreno says. “To me that’s my best way of resisting, by showing I have power for myself and no matter the obstacles you place me in, I will overcome.”

Carreno has plenty of company. In the days following the election, thousands of California school kids in cities including San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, San Jose, and Los Angeles walked out of class to protest Trump’s win. Elsewhere in the country, student walkouts occurred in other cities, as well. It was Carreno who helped organize peers from Leadership High to join the San Francisco action on November 10, but she didn’t want their efforts to end there.

“We made headlines, but what’s going to come after?” she says. “Are we going to continue to protest?”

Carreno’s teacher José Montenegro suggested that she spearhead a combined student-faculty committee to fight what they fear will be a rise in prejudice and inequality under Trump. “It’s mostly anti-Trump, but also just unifying ourselves as minorities and as people who are tired of this racism, this ongoing racism that has happened for years,” she says. The committee is also collaborating with a teacher-led effort in Oakland and is reaching out to schools in Los Angeles.

Montenegro says the effort is built on a school tradition of students doing presentations and even leading classes. “We have school-wide assemblies where we have student emcees and whatnot,” says Montenegro, who teaches “leadership,” a social studies class with an activist flavor. “We do talk about resistance from (December 17, 2016) to today.”

Left Meets Right

Established in 1997, Leadership High School states that over 94% of its graduates go on to college. It’s a success story to bolster the arguments for charter schools, a priority for conservatives like Trump’s Education Secretary nominee Betsy DeVos.

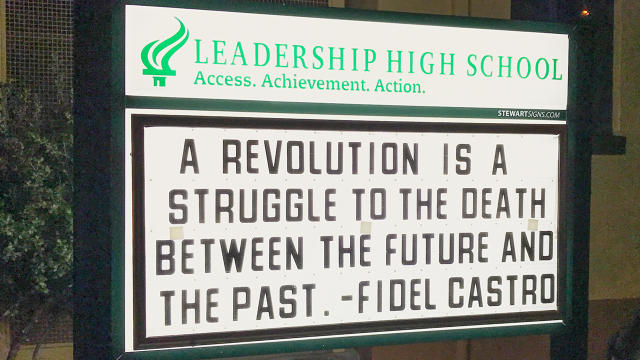

But Leadership High has very different political orientations than your average conservative donor. The school administration gave permission for hosting the anti-Trump organizing event, says Montenegro. His classroom is bedecked with left-leaning posters, such as one with the popular immigrant activist phrase, “Ningun ser humano es illegal”—”No human being is illegal.” On the night of the meeting, the illuminated letterboard in front of the school features a quote from Fidel Castro: “A revolution is a struggle to the death between the future and the past.”

The leftist high school fits a San Francisco cliché. But it’s an older one from before the tech boom that created a chasm between the largely white wealthy new arrivals and the lower-income and often minority longterm residents. This opulent, deep-blue city faces a social and economic gap as broad as any that’s emerged in America, post Great Recession.

Montenegro and other teachers from Leadership High share the stage with students like Carreno. Most are of Latino or African-American heritage, reflecting the two main ethnic groups in the Leadership High student body. But the collection of teachers gathered from around the city this night is more diverse, which in this context means that there are more white people. Their challenge is a common one for a new meeting of activists: how to decide what to do, when, and where.

A massive protest on January 20, Inauguration Day, is a given, but they want to start earlier, with outdoor teach-ins followed by a march on December 16, the last day of classes before the winter break. I sat in on the Political Education committee breakout group of teachers and students that night, headed by Montenegro, which brainstormed ways to educate students and the public on the political and social forces at work.

“We know it didn’t come out of thin air,” says Montenegro, who addresses the participants gathered in his classroom as “sister” and “brother.” “It’s been a process that’s been done over the last decades.”

The movement still needs a name. “Teachers Against Trump” has been tossed around, but it hasn’t caught on. “It’s so much more fun to get critical mass and to crowdsource and discuss,” says Susie, a technology teacher at another San Francisco school. She asked that her last name and school not be used because she didn’t want her political leanings to be made public—a concern that other teachers echoed. “I guess we need a name for a website,” she says, chuckling. “We need a hashtag.”

That’s where the students can help. Carreno and her friends are heavy Twitter users, she says. “We’ve been keeping up with activists that are really into the Black Lives Matter movement, also been keeping an eye on Colin Kaepernick, because his movement’s been really big,” she says about the San Francisco 49ers quarterback who has sat in protest during the Star Spangled Banner. “It’s really how we connect.” The San Francisco walkout was organized within 24 hours, mostly on Instagram and Snapchat.

“They understand getting the message out really well,” says Susie. “The kids know to send a link,” she says with a hearty chuckle, “or a picture or a logo. I mean there’s a whole bunch of things that we could use to launch this.” Her concern is that kids aren’t as adept at telling truth from lies online—an increasing problem in what she, like many others, calls the post-fact or post-truth era.

Susie and other teachers are also worried about privacy and security. Another teacher in Montenegro’s discussion group made a pitch for the free encrypted chat app Signal, from Open Whisper Systems. “If you’re going to talk about some of this stuff, please use Signal, because you are probably being monitored,” he said, without providing any evidence.

As for the students, their opinions vary. “They are using tech against us,” says 18-year-old Leadership High student Javier, citing worries about the NSA. He suggested building a secure message board for anonymous communications.

Carreno also assumes she’s being watched, but she forms a different conclusion. “Our generation especially uses a lot of social media to promote things,” she says. “You know your brand, if it’s out there in social media, people are talking about it. That’s how you create buzz.”

With that, she takes a lesson from Kanye West, who she says has to keep posting online to stay relevant. Ironically, it’s the same strategy employed by Trump himself. “If you’re not being talked about in social media, if you’re not advertising yourself in social media, then how are you going to get people to listen to you?” Carreno asks.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(29)