This biotech is re-engineering cells to fight one of the cruelest cancers

By Sy Mukherjee

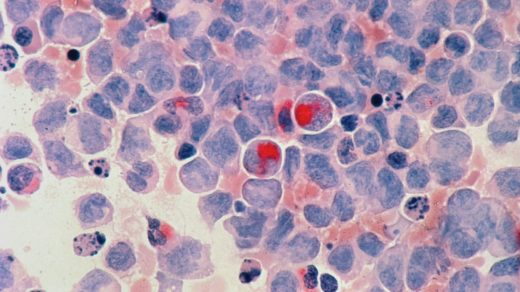

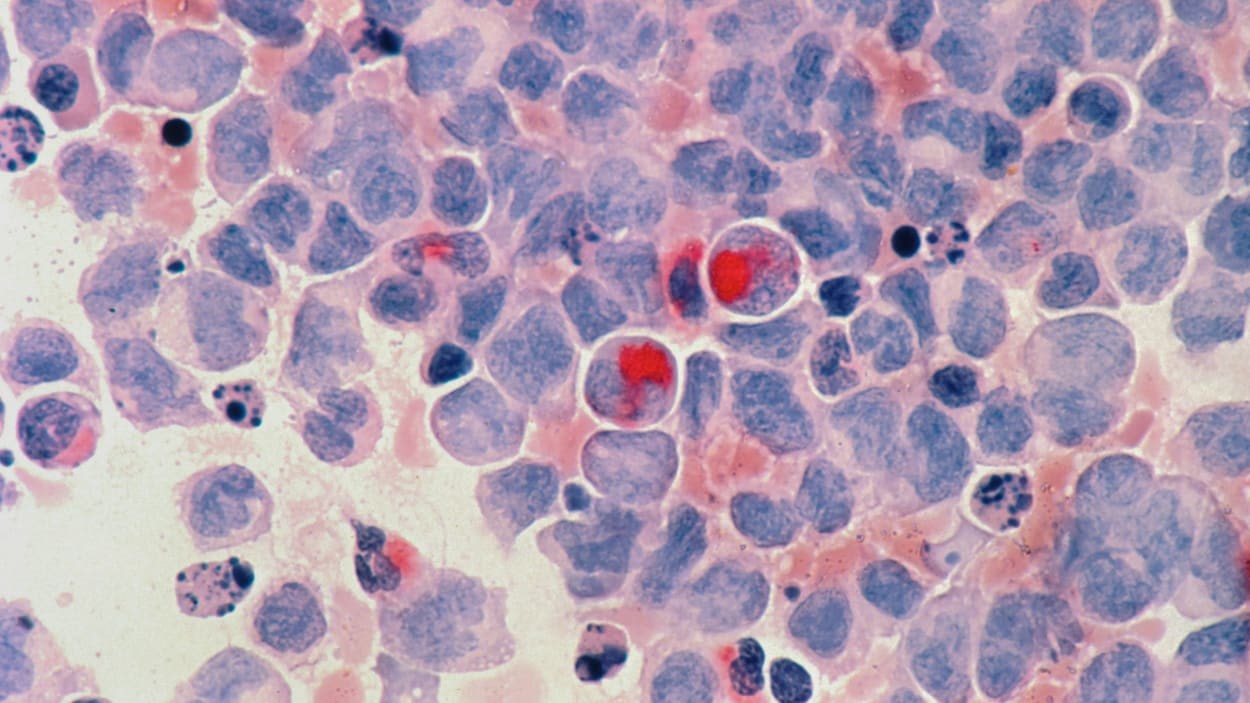

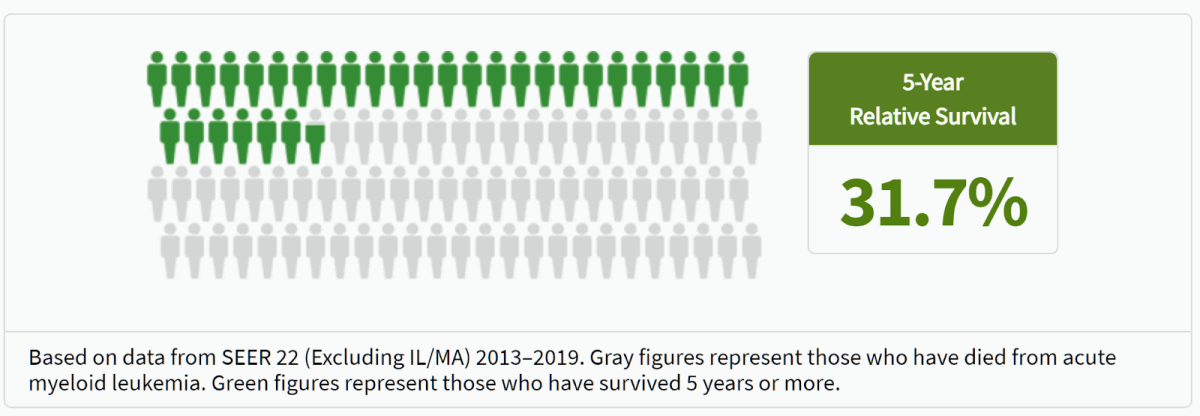

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) isn’t the most commonly known cancer. It is, however, one of the deadliest—an awful rare malignancy of the blood and bone marrow whose victims are already older and frail, on average 68 years old when diagnosed. It has few treatment options—chemotherapy is most common, according to the American Cancer Society—and any available ones must be deployed immediately after it’s diagnosed given how rapidly this aggressive cancer spreads. Nearly 70% of AML patients die within five years of diagnosis, and life spent in treatment for those who survive is a carousel of draining, painful treatments, hospital stays, and dependence on dedicated caregivers.

The only thing approaching a cure for AML is a life-saving procedure called HSCT, a stem cell transplant that wipes out the cancerous bone marrow entirely so new, healthy cells can form from a donor’s stem cells and create new, healthy blood. But it’s a drastic option that requires “conditioning” patients with chemo to wipe out the diseased cells, followed by the process of getting stem cells from a donor and injecting them into the patient, allowing those cells to mature and multiply within the patient’s bones—all while that patient is confined to a literal bubble at a hospital (without a healthy arsenal of marrow and the white blood cells it produces, even a simple infection can spell death). And then you have to hope the cancer doesn’t resurface and lead to a relapse that would require even more painful procedures–an unfortunately common occurrence as 30% to 40% of AML patients who receive a stem cell transplant relapse.

Stem cell transplants are unlikely to go away since, drastic or not, they’re the only curative option out there for AML patients. But Vor Bio thinks its biotechnology can give these typically elderly patients a better shot at life with a targeted approach that avoids wrecking the whole marrow system. And that strategy is showing early promise in the clinic in one of the most aggressive blood cancers, Vor CEO Robert Ang and chief scientific officer Tirtha Chakraborty told Fast Company during a sit-down interview at the 2024 JPMorgan Healthcare conference last month. Chakraborty served roles as a lead scientist at both the CRISPR gene-editing firm CRISPR Therapeutics and mRNA pioneer Moderna prior to joining Vor.

There are several CAR-T therapies from such companies as Gilead arm Kite Pharma, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, which are already FDA-approved to treat certain blood cancers such as leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma. The process typically involves extracting killer immune cells from a patient (this is called an “autologous” approach, as opposed to an “allogeneic” approach that uses healthy cells from a donor), re-engineering them in a lab to become cancer killers that can identify the tell-tale signs of an aberrant cell, and then re-infusing these supercharged cancer-killing T-cells into patients. No CAR-Ts are approved to treat AML, though several companies are testing out experimental products to fight the cancer.

While Vor’s basic approach is the same, CEO Ang says it’s sophisticated and precise, using the “allogeneic” technique of taking healthy cells from a donor and tweaking them to seek out a biological target, an “antigen” called CD33, which serves as a homing beacon of sorts to guide the re-engineered immune cells to cancerous ones with the CD33 antigen. CD33 is typically on the surface of white blood cells called myeloid cells (including the aberrant ones which cause acute myeloid leukemia). But the twist is that CD33 isn’t just present on cancerous AML cells–it can also present on healthy white blood cells.

And that’s where Ang and Chakraborty say Vor’s allogeneic VCAR33 therapy has an edge in helping patients, with early clinical results suggesting its method for wiping out all CD33 in the blood marrow system doesn’t destroy it. It’s possible the approach may prove safer and more effective than others since Vor’s reengineered cells are made from the same healthy donor cells that were used for the patient’s transplant.

“Other CAR-Ts in AML have just made a bigger hammer, and that hammer will destroy the blood system. And now it’s like, okay, you’ve got empty bone marrow, sorry, but at least hopefully, you don’t have cancer. But you now need new bone marrow,” he said.

Ang and Chakraborty say, given the high relapse rate for AML patients who receive a stem cell transplant, a biotechnology which creates cells that can attack cancerous adversaries by zeroing in on a tell-tale receptor present in those cell types, while preserving healthy cells of that same type is the best possible outcome–and, in a small early sample, one that’s possible with Vor’s platform. “We have eight patients that we’ve publicly disclosed that we’ve treated with this, they now have bone marrow that’s empty of CD33–and they do just fine,” said Ang.

Hematology and blood cancer experts have pointed to CD33 as a promising target for experimental AML treatments given how commonly the antigen is expressed in these cancer patients’ cells, and Pfizer’s Mylotarg (a non-CAR-T therapy that targets cells which express CD33 through a different approach), is FDA-approved for AML patients whose don’t respond to other treatments or whose cancer reoccurs–but comes with the risk for potentially deadly side effects in some people.

A successful CAR-T approach for combating AML has proved elusive. But for now, Vor’s Ang is optimistic about VCAR33’s potential to buck that trend given the early available evidence. Vor announced it had dosed the first AML patient in a phase 1/2 clinical trial of its allogeneic VCAR33 platform on January 17.

(18)