To redesign democracy, the U.S. should borrow an idea from Dublin

By Claudia Chwalisz and Zia Khan

In the winter of 2013, two men found themselves on a surprising journey. Finbarr O’Brien, a traditionalist Catholic in his late fifties from rural Ireland, and Chris Lyons, a gay man in his early thirties from Dublin, were both randomly chosen from the Irish electoral register. They were about to join 64 of their fellow Irish citizens in a groundbreaking democratic experiment: a citizens’ assembly—jointly proposed by the center-left Labour and center-right Fine Gael parties as a way to move forward from perennial, divisive debates about amending the Irish Constitution, starting with provisions on same-sex marriage and abortion.

Little did Finnbar and Chris know that not only would this process impact the fate of same-sex marriage in Ireland, but it would also forge an unlikely yet profound friendship between the two men. This was the meeting of opposites—a rare encounter that can only emerge in a neutral space where preconceived notions are set aside in favor of respectful dialogue. At a time when polarization and partisanship create political stalemates for democratic governments worldwide, new tools are required to strengthen the social contract. This may be one of them.

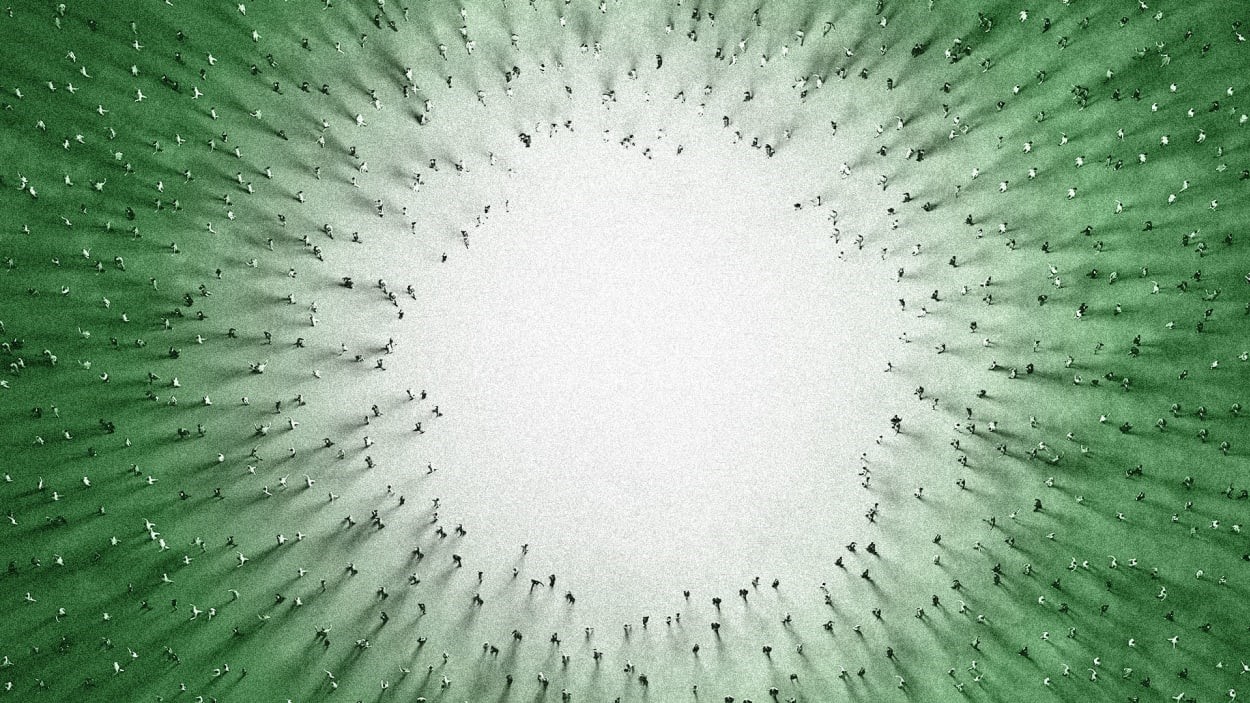

Let’s start with some of the mechanics: The typical citizens’ assembly convenes community members from all walks of life to study, deliberate, and provide recommendations to policy questions on behalf of the larger public. Crucially, these representatives are randomly selected through a lottery (also known as sortition) and serve temporarily, as with jury duty. The idea is to reach beyond the typical folks who show up at a school board meeting or that run for office but instead engage a true cross-section of the community. Assemblies make every citizen a potential representative of the people, not just a vote to be turned out.

While citizen’s assemblies were eclipsed as a tool of governance as elections came to define democracy, the idea actually dates back to ancient Athens and shaped early democratic institutions in America, like the jury system. Now, as the United States grapples with its own challenges of division and discord and the 2024 elections loom, this old idea points us toward new ways of giving people real voice and power.

Assemblies can create good conditions for people to have honest conversations, grapple with tradeoffs, and understand different points of view. As shown in other equally diverse and large countries, citizens’ assemblies can be instrumental in addressing issues that have proven particularly divisive or have been susceptible to political stagnation, such as homelessness, climate change, land use, safety and policing, abortion, transgender rights, migration, and others.

In most places, assemblies have been only advisory thus far—but the moral authority of speaking on behalf of the people and hard-won consensus can be powerful. In Ireland and many other places, they’ve been organized by public authorities as a way to supplement input from elected officials.

While the very first Irish Citizens’ Assembly was organized bottom-up by academics, the subsequent Irish assemblies have been initiated by the government and have become an established part of how Irish democracy works. Today, ministers want their issues put to the next assembly.

As Art O’Leary, the chief executive of Ireland’s Electoral Commission has said: “What [the Citizens’ Assembly] has done is provide a safe, respectful, and equal environment in which to have a conversation about things that governments, our political system, and our society find difficult to talk about . . . we now trust the [Citizens’ Assembly] system, and we have the spectacle right now of the political system fighting amongst themselves to have the next issue to be discussed by the next Citizens’ Assembly.”

As the 600 examples counted by the OECD demonstrate, you can find citizens’ assemblies functioning successfully in Australia, Belgium, Germany, Brazil, Chile, Mongolia, Japan, and beyond. Citizen’s assemblies could also work in the United States.

Here are three principles behind why citizens’ assemblies work:

First, citizens’ assemblies recognize that everyone has something to offer. By relying on selection by lottery, they recognize that everyone has agency and dignity. We are all worthy of being selected to represent others. Lotteries are a consciously neutral procedure that justly distribute political opportunities. Instead of feeling like passive spectators, citizens become active contributors to the democratic process, engendering a sense of ownership and responsibility.

Interviews with former assembly members around the world bring this point home. For instance, at the recent French Citizens’ Assembly on End of Life (November 2022–April 2023), a younger woman of immigrant origin shared: “I feel really free to speak, to give my opinion, to express myself and be respected.” While one of her older counterparts recounted: “I leave with a much more enlightened view of the question of the end of life, a confidence in citizenship and in democratic innovation.”

Research from the OECD and other sources show that it is common for the experience of being an assembly member to awaken a sense of political efficacy, meaning people feel that they are able to have an influence on political decisions. They are more likely to volunteer and get involved in their communities afterward. Imagine what this could mean for civic engagement in the U.S., where polarization and political disillusionment is now as much a calling card for the country as democracy. It gives hope.

Second, citizens’ assemblies create the conditions for people to grapple with complexity and find common ground. They are structured in such a way as to give participants ample time to learn, weigh trade-offs, and build trust. Moreover, there are secondary benefits to bringing diverse groups together for thoughtful, collective problem-solving: These circumstances nurture grounds that bridge divides, reduce polarization, and honor citizens’ role in defining what society wants, which, ultimately, allows experts, governments, stakeholders, and fellow citizens to realize shared goals.

In the French assembly mentioned, the 184 Members deliberated for 27 days, hearing from over 60 experts in the widest sense of the term—including people with lifelong illnesses, faith group leaders, philosophers, and civil society organizations, as well as researchers and doctors. They had the deliberative space to consider the issue from all angles and to collectively draft 67 recommendations for the government. Remarkably, they achieved 92% consensus on their proposals, which included suggestions to legalize euthanasia and assisted dying. The process enabled them to find such high levels of common ground. On prime-time TV, one of the assembly members who personally opposed the liberalization of the law explained why she nonetheless voted in favor of the proposals:

“It’s democracy, it’s the game. In this Assembly, everybody was listened to. When you read the report, there is a large part of the work that is about palliative care. It’s because of this that those of us who were against some of the measures voted in favor overall because we felt that we were really listened to.”

Third, citizens’ assemblies strengthen trust. There is a common refrain that today we are facing a crisis of trust in government by people. The flip side is also true: there is a crisis of trust in people of the government. And there is arguably a crisis of trust between people as well. There is no shortcut to this problem. In these assemblies, people gain empathy for the difficulty of making hard choices in power. Governments gain confidence in the capacity of everyday people. And people come into extended contact with others from all walks of life, breaking down assumptions about ‘others.’

It’s high time that local leaders inside and outside of government, in red, blue, and purple jurisdictions, begin to consider citizen’s assemblies as a practical option for re-establishing a common ground.

Back in Ireland, despite their starkly different backgrounds and viewpoints, Finnbar and Chris found common ground in their commitment to giving this experiment—the Constitutional Convention—their all. What’s more, as they and their fellow assembly members studied, deliberated, and debated over several months, something remarkable happened.

Finbarr, initially opposed to same-sex marriage, found his perspective shifting as he really listened to Chris and other members of the gay community. Chris, coming into the assembly with conceptions of “old Ireland,” came to have empathy for a man who revealed that his initial opposition to same-sex relationships stemmed from having been molested by a man as a child. Stereotypes and prejudices on both “sides” came down.

This evolution of thought, the flowering of understanding amidst a platform of respectful dialogue, personifies the true essence of citizens’ assemblies.

There have now been around a dozen citizens’ assemblies in Ireland, leading to three other referendums—all successful—on constitutional change regarding abortion, divorce, and blasphemy. Citizens’ assemblies shaped Ireland’s Climate Act, informed its decisions on devolution to Dublin’s mayor, and have influenced forthcoming legislation and potential constitutional amendments on biodiversity and many other issues. The Irish experience—and that of hundreds of similar examples in other countries—has revealed that regular people can navigate complex issues just as well as – if not better than – politicians.

Though they will require us to flex muscles that we don’t use enough, citizen’s assemblies are a simple, radical, and pragmatic way to get around the short-termism of electoral battles, gerrymandering, and money in politics that clog our democracy today—a concrete way to change our politics for the better.

Claudia Chwalisz is the founder and CEO of DemocracyNext, a nonprofit organization that aims to shift political power to citizens through citizens’ assemblies. Zia Khan is a senior vice president and chief of innovation at the Rockefeller Foundation.

(8)