True.ink is a horse-buying, whiskey-bottling non-media media company

I’ve talked with Geoffrey Gray a total of four times, along with multiple email correspondences. The first time we met in a trendy Lower East Side cafe. The second time I called his American phone number, which forwarded to a not-American ring sound, and he answered his cell phone from Mexico City. I think he called me “muchacho” when he answered the phone, but I can’t quite remember. The third time we FaceTimed while he walked along a horse farm in Kentucky.? This latest time we find ourselves at the Explorers Club in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the storied private society for swashbucklers, scientists and everyone in between.

Gray has just flown in from Mexico City, arriving at his lower Manhattan apartment in the wee hours. I go to shake hands, but he indicates he’s going for something different–leaving me in that awkward situation where I’m not sure if I’m shaking, hand-slapping, or something else, so I go limp and hope his momentum will lead me toward whatever salutation we decide upon. Gray, instead, instructs me on how people in Mexico greet each other; it’s a mixture of a handshake, high-five, and ends with a quasi-hug–“heart-to-heart,” says Gray. I fumble through the motions but sort of get it.

We walk along the old wood floors of the eerie New York building, while pictures of old dead white men and corpses of old dead animals towering over us. We decide to sit on the outside deck, which is shielded by both the Explorers Club building and the others adjacent to it. Though you can hear the cacophony of the city–children playing at a nearby school; a jackhammer hammering on the street below–this weird destination feels like a haven of sorts: a nostalgic fort defending the monotonous dragging of time. After our initial conversation, we get up and Gray excitedly asks, “Do you want to see some stuffed bears?” Of course I do.

The setting of our meeting makes sense, and explains why I’ve been so interested in Gray. He’s an interesting figure–someone I knew I wanted to write about ever since we first met, but I could never figure out what exactly I would write about. Gray is the founder of True.ink, which is sort of the resurrection of an old magazine, but not really.

The original True is a publication that time has seemingly forgotten. It was a monthly chronicle of men doing manly adventurous things. It was a hyper-masculine magazine that idealized what it meant to be a modern, 20th-century swashbuckling male. In case I haven’t driven this point home enough, the publication’s full name was True: The Man’s Magazine. It was known for its harrowing chronicles of worldly adventure. The magazine ended in 1975, I have a feeling that the ethos it presented would have a hard time adapting to modern day. Like most beer (a drink that manly men love), some things don’t age well. The old True surely showcased some real talent–such beloved names like Ernest Hemingway, Aldous Huxley, and Winston Churchill all wrote for it. The magazine was a perfect encapsulation of what the intellectual man strived to be. Gray tells me later on that other male-centric magazines like Playboy and Hustler superseded True with their female fetishization. But, he says, “True never went that way.” He adds that trope of a personal adventure story–from the perspective of ‘I did this’–is something that has fallen out of editorial vogue, except maybe for blogs that took these narratives in another direction.

Gray’s backstory is an interesting one. He’s been a professional writer for most of his career–first writing about boxing for the New York Times, moving to the Village Voice where he wrote about crime and eccentric personalities in the city. Then he covered the police and crime beat for nine years at New York Magazine. Gray’s Wikipedia entry (which he tells me was written predominately by a friend who interviewed him) adds to his mystique. “Gray is known for his eccentric choice of subjects, profiling a tour bus driver that also served as a Nigerian king, the world’s most daring fragrance expert, and the world’s most gored matador,” it states. “Gray’s interest in underdogs is a common theme in his works.” He’s a man who wants to telegraph that he loves a good story. So it’s not entirely surprising that he experienced a fondness for the defunct True magazine.

Yes, it’s true that Gray is an odd and interesting fellow, but that wasn’t the only thing that interested me. It was this True resurrection that caught my eye, not because it was an old magazine starting anew but because this new iteration wasn’t a magazine at all and every time Gray explained the project to me I never quite understood it. True, he tells me during one of our earlier conversations, “is very much like a spirit–a state of mind.” It’s a “feeling of achieving something extraordinary.” But what does that means??? For Gray, it means he’s building a company that sells experiences, but atop this old magazine branding.

True sells various trips, activities, and other unique once-in-a-lifetime happenings. People pay into it and they get a “Lucky Piece,” which is a round disc that signifies the company’s distinctive access. Members can show off their lucky pieces as if it’s an entry pass into a cool club. A piece costs $249. From there, they get access to these other experiences, which they also have to pay into. They also get access to content from Gray’s editorial team, often written from the perspective of what other members are up to.

During our first meeting, Gray was talking up a storm about all of his plans. They included a horse project, which allowed members to buy access into a then-unborn horse, who would hopefully go on to be a top racer. He was also planning on moving to Mexico City with his team, because why not. There, he would check out various hot spots and potentially host upcoming member trips.

During this time, I’m definitely interested in the True project, but I’m still addled by that age-old question of what the hell kind of media company is this. He tells me that the magazine is now simply part of the experience. People who are part of True’s user-base are given the keys to have their own adventures, similar to the ones written about in the ’30s and ’40s up until the ’70s when the magazine died. True members can become their own Hemingways; True gives them access to unknown, non-touristic experiences, and provides them with content that uniquely chronicles these types of adventures. True is a non-media company based on a now-dead fantasy about what media once was.

I dawdled with all of this. I was still intrigued and wanted to hear more about Gray and the company, but didn’t know exactly what to write. If this is a media story, what exactly is the story? Is it that media is dead and this company believes that monetization can only happen when you take away the annoying writing and editing part? There is absolutely something to be said for a media company that avoids the pesky media parts. Tech giants like Google and Facebook are vacuuming up ad dollars and eyeballs, so it’s difficult for any independent company to get their voice heard. Editorial budgets are shrinking and magazines are folding. What True, the new company, wants to do is make members feel like their part of a magazine while selling something different. Gray still insists that the editorial ethos of True–the old magazine, that is–exists. And there is still an editorial element: He has staff who write about the myriad experiences the company offers, and Gray tells me he sees media partnerships down the horizon.

Still, I waited unsure of what exactly to say. Then the horse project officially launched. Called “The People’s Horse,” Gray and his team let people pay a minimum of $149 to buy access into an equine fetus. The foal’s parents are two prize-winning horses, including California Chrome who won both the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes in 2014. Members bought a stake in the horse while she was in utero, and were given a camera to watch the gestation period. Once the horse is born, True members who bought into the horse would be given the chance to visit her at select dates, as well as attend future events surrounding the horse. They could even shell out $40 to send the horse a care package of carrots (expensive carrots, if you ask me). There’s also, of course, the chance that she could become a top racer given her pedigree–which is likely one of the big draws for buying a stake in a horse through an adventurer magazine that’s not actually a magazine. Down the line, Gray says that members will be given the chance to buy equity into the horse.

The horse was born a few months ago and still I had nothing to write. Gray and I sent a few emails as updates and we continue with our lives–mine in New York, his in Mexico and probably other places, I imagine he travels a lot. A few weeks later he emails me again about another True project, one involving whiskey. He tells me he could give me the exclusive. Sure! I say–I’d love an exclusive; what reporter doesn’t love the word exclusive? Finally, a reason to write!

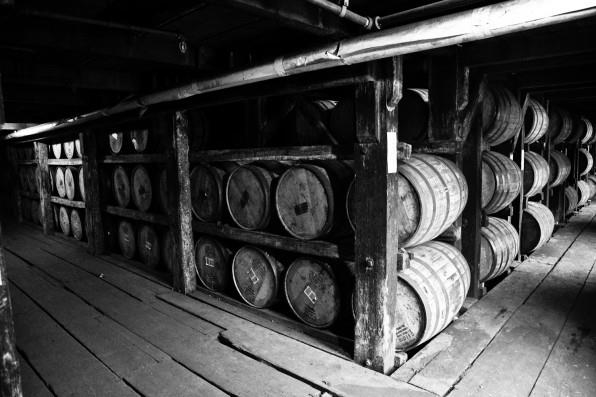

So here it is: True is partnering with Buffalo Trace bourbon. Similar to the People’s Horse, this experience gives members the chance to buy into their own barrel of whiskey this coming October. The Buffalo Trace partnership is line with other True experiences, like the People’s Horse. The idea is to let members buy into a privileged experience–one they wouldn’t be given access to elsewhere.

I meet up with Gray at the Explorer’s Club to discuss the whiskey project. I instantly make a faux pas when I describe the barrels as kegs, thus proving even further my philistinism. Gray respectfully corrects my error and continues explaining the concept. A barrel of bourbon, he tells me, takes eight and a half years to make–that’s a longer gestation period than a racehorse, he remarks. “We’re thirsty, and I don’t know if we have eight and a half years to wait to sample our bourbon.” And so Buffalo Trace is letting select True members travel down to the distillery and have them taste three separate barrels. Over the “bacchanalian weekend,” as the website describes it, participants will taste a slew of whiskey, and have a true Kentucky experience–for $875. The weekend trip is capped at eighteen people. Once the trip is over, these members will be asked to report back to the others–who bought a less expensive version of the experience–about their thoughts on the three whiskey choices. These members can buy into the barrel for $129, and receive voting rights based on the weekend chronicles, as well as a bottle of the spirit once its chosen. Non-members can buy into both the whiskey and a year-long True membership for $249. The entire whiskey experiences caps at a little under 200 people (which is about how many bottles, give or take due to evaporation, a barrel of whiskey can make).

From there, Gray’s and my conversation veers into the various plans for True. Since we first met, he was always one to talk about the crazy forays his company allows him to do. In Mexico last year, he helped lead people through Tlaxcala. Because there is no way I could ever do it justice, let me simply copy and paste the experience description from True’s website:

The wisdom of the ancients can still be taught, and we have an appointment with the masters in Ixtenco, a traditional village on the altaplana or colonial highlands of Central Mexico.

Ixtenco is home to the Otomi, a tribe known for their practice of nagualism, a shamanistic belief that humans can transform into animal spirits (typically puma and jaguar) and vice versa.

We’ll be visiting with Don Mateo, an Otomi elder who has agreed to teach us his language and customs during the holiest time of the year: Dios De Los Muertos or Days of the Dead.

But this was last year’s experience. Already, he’s getting ready for the next one, which will be this fall. Attendees will take over a 15th-century hacienda, where they’ll experience and learn about the Tlaxcalan culture. “They worship the jaguar,” he tells me. “They have some very unique things that are native there. One is pulque, which is sort of like the old drink of the gods, which is fermented maguey–honey water from the inside of the maguey plant. And we also have a shaman that we do a temazcal with, his name is Galo. And there’s also some bull ranchers who we’ve become friends with, so people can cape bulls if they want.”

Gray also has plans to lead people through a Peyote ritual. Another experience in the pipeline Gray describes, in Oaxaca, will take members to a local potter. “This woman who makes pottery by hand, does it the old style way. They use a brush fire for the kiln.”

He has a million stories to tell of experiences True has led and others he plans to facilitate. His team is setting up excursions to wineries in both California and Uruguay. People would be able to see the vineyards and taste one-of-a-kind grapes from unique growers Gray has come to know over the years, whose wine is unique and a cut above the rest.

We go back to the subject of the People’s Horse and Gray informs me that the foal has sadly lost an eye. Every true experience, I suppose, needs a tinge of tragedy. It’s unclear exactly what happened, but something lacerated the animal’s cornea late in the night, and the veterinarian said that the organ needed to be removed. Gray adds that this doesn’t completely kill the horse’s shot at being a first-class racer–many horses have lost eyes and been able to compete down the line. Not all is lost.

Concurrent to all of these, Gray and his team write about the experiences as well as ask members to write about it too. Though I was unable to travel to his Mexico City office, I imagine it to be a sweaty room with a few men intent on using their most flowery language to illustrate Adventure. Hunched over computers, they spent the winter building up True to be a way for people to find these once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. All the while, there’s this necessary editorial visage they had to maintain. Gray is Hemingway’s assigning editor, and he’s letting anyone who pays into his company be Hemingway. Gray tells me that members who were in Mexico City would sometimes stop by and hang with the team.

Which leads to the thorny subject I’ve been trying to understand since the first time we met some five months ago. True has been described in the media before as a sort of digital magazine, but that’s not quite right–even Gray admits that to me. The business offers a weekly newsletter that he and his colleagues keep up, and they connect with other members and try to amplify the stories they tell about the experiences they had. But it’s about what people do with True, not the stories that get published after the fact. We begin going down this pathway when Gray brings up some partnerships. “I think one of the things we want to do with True is that we want to work with other startups, other impassioned communities that have a passion about something,” he says. Along with the Buffalo Trace partnership, he mentions two alcohol e-commerce companies, Caskers and Saucey, with which True is launching promotions related to the experience. But True isn’t selling the whiskey, nor is it exactly selling a trip to see whiskey being made. It’s doing something in between.

Gray, when describing his business, goes off on many tangents. Sometimes I get what he’s saying and other times I’m a bit hazy. He sees True’s place as being a crossroads of many products. It allows there to be a media aspect to other businesses; “I see this convergence of industries–between e-commerce, which needs to have their own media; platforms that need to have their own media; us–which is media based but it’s really not a media business; and even traditional publishers.” From there, he talks about True’s distribution opportunities. For now, the company relies on email and its website–along with a few promotional partnerships with websites like Esquire and The Hustle. The website publishes stories that members can read as well as pushing this content via newsletters. He sees private messaging–for instance, WhatsApp–being another way to connect with members internally. Externally, Gray sees True becoming a more prominent syndicated content creator.

“The demand for syndicated content–or good content that actually stands up–has never been higher,” he says. “So many publishers, so many e-commerce companies, so many hotels, so many… you know… everyone needs content. And I think that True has plans to be the leader of our own kind of syndicate.” He says True is already in conversation with other brands and publishers about these partnerships, but that’s in the future. “I don’t think we can do it this year, but I definitely see that happening.”

For Gray, he envisions True as a business that lets everyone participate in their own magazine. Whenever we talk about the media industry, he always brings up engagement and how difficult it is for publishers to find and engage audiences (and he’s right!). Gray sees his company as circumventing that altogether. I tell him that perhaps he’s in a unique place as a media company, given he’s not quite a media company and he has paying members who are already actively engaged. Still, he goes on, there’s something more to it too. “Having come from media for so long, and having been in that world for so long, and being a maker of it, I think that this [engagement] challenge is so different because it’s actually trying to get down to understanding what makes people tick and engaging them through their own desires–not mine, and not the magazine’s,” he says. “It’s trying to be a facilitator, in a way, and a producer. As opposed to being a [creator] of narrative nonfiction.”

After our patio conversation, Gray and I wander more through the halls of Explorers Club. We go up to the archives where he shows me lantern slides made by Kermit Roosevelt, Teddy Roosevelt’s son. The slides, which are old photographic transparencies that are hand painted–kind of like the first iteration of a Powerpoint–show the wild adventures Roosevelt had. This one showed a camp of people during one of his many expeditions. Meanwhile, Gray describes to me a boy named Benjamin who is True’s youngest member. He’s 10 years old and is going to climb Mount Kilimanjaro with his father.

This is the kind of perfect story and experience for True, Gray tells me. “It’s cool to have a member who’s 10 years old and who’s totally going through all of what you would go through as you set out to embark on an extraordinary quest. He’s nervous, he’s training, and he’s with his dad. And, you know, there’s a big history of fathers and sons in the adventure arena,” he says gesturing toward the Roosevelt slides. This is the kind of story True, the old magazine, would have Benjamin–or his father–write after the fact, if it were still around. Instead, Gray is facilitating this adventure and allowing the boy’s story to be told as some ancillary part.

We continue meandering through the building, I continue asking questions about the business. Gray walks me out of the building and down the street and I put out my hand for a handshake. He, of course, goes for the Mexican salutation he’d taught me earlier. We slap hands, sort of finish the backhand gesture, I fumble through the hug; I almost do it but not really. Perhaps I’ll get it next time.

This story has been updated to clarify “The People’s Horse” experience. An earlier version of this story misstated a True member’s name and the location of the horse farm. We regret the error.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(27)