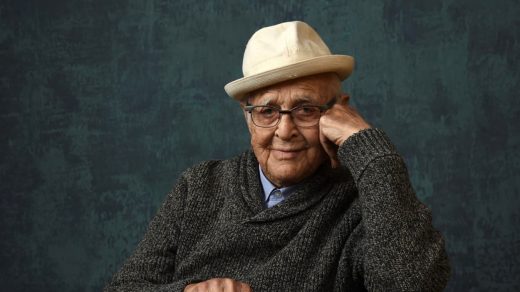

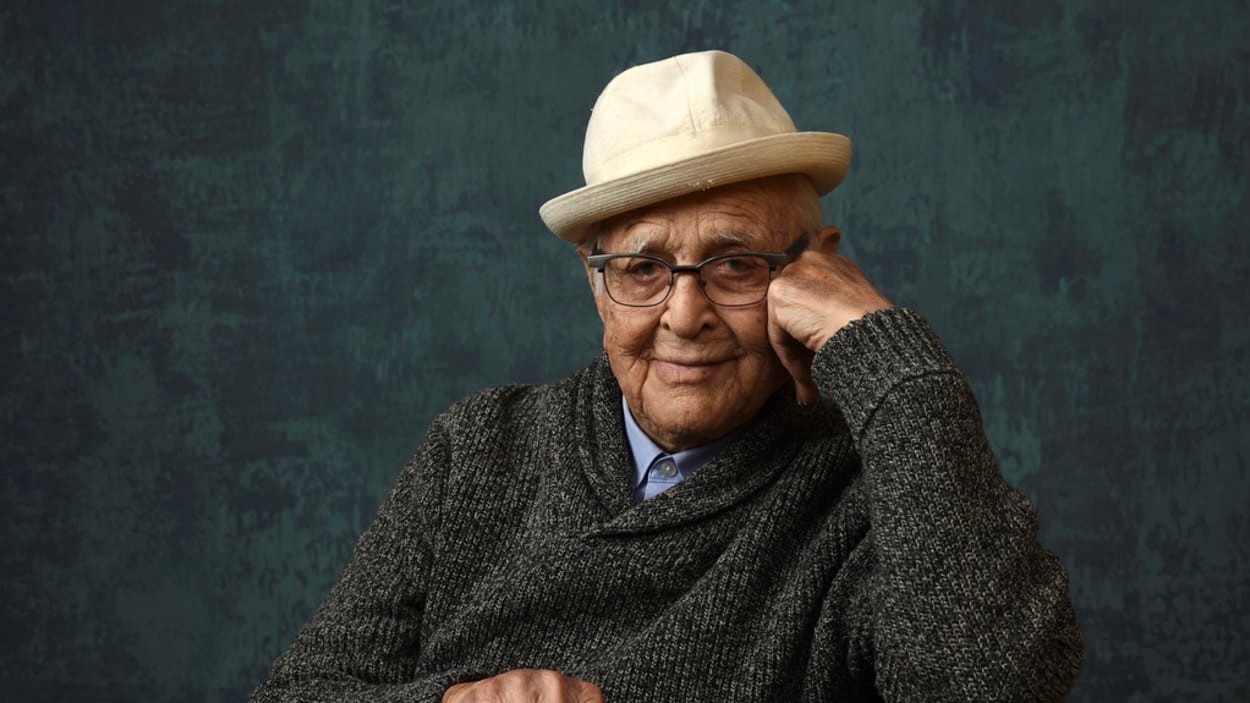

TV pioneer Norman Lear, producer of ‘All in the Family’ and many spinoffs, is dead at 101

Norman Lear, the writer, director, and producer who revolutionized prime time television with All in the Family and Maude, propelling political and social turmoil into the once-insulated world of sitcoms, has died. He was 101.

Lear died Tuesday night in his sleep, surrounded by family at his home in Los Angeles, said Lara Bergthold, a spokesperson for his family.

A liberal activist, Lear fashioned bold and controversial comedies that were embraced by viewers who had to watch the evening news to find out what was going on in the world. His shows helped define prime time comedy in the 1970s, launched the careers of Rob Reiner and Valerie Bertinelli, and made middle-aged superstars of Carroll O’Connor, Bea Arthur, and Redd Foxx.

“I loved Norman Lear with all my heart. He was my second father. Sending my love to Lyn and the whole Lear family,” Reiner wrote on X, fomerly Twitter.

All in the Family was immersed in the headlines of the day, while also drawing upon Lear’s childhood memories of his tempestuous father. Racism, feminism, and the Vietnam War were flashpoints as blue collar conservative Archie Bunker, played by O’Connor, clashed with liberal son-in-law Mike Stivic (Reiner). Jean Stapleton costarred as Archie’s befuddled but good-hearted wife, Edith, and Sally Struthers played the Bunkers’ daughter, Gloria, who defended her husband in arguments with Archie.

Lear’s work transformed television at a time when old-fashioned programs as Here’s Lucy, Ironside, and Gunsmoke still dominated. CBS, Lear’s primary network, would soon enact its “rural purge” and cancel such standbys as The Beverly Hillbillies and Green Acres. The groundbreaking sitcom, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, about a single career woman in Minneapolis, debuted on CBS in September 1970, just months before All in the Family started.

But ABC passed on All in the Family twice, and CBS was initially reluctant to take on the daring series, Lear would say. When the network finally aired All in the Family, it began with a disclaimer: “The program you are about to see is ‘All in the Family.’ It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show, in a mature fashion, just how absurd they are.”

By the end of 1971, All In the Family was No. 1 in the ratings, and Archie Bunker was a pop culture fixture, with President Richard Nixon among his fans. Some of his putdowns became catchphrases. He called his son-in-law “Meathead” and his wife “Dingbat,” and would also snap at anyone who dared occupy his faded orange-yellow wing chair. It was the centerpiece of the Bunkers rowhouse in the New York City borough of Queens, and eventually an artifact in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Even the show’s opening segment was innovative: Instead of an off-screen theme song, Archie and Edith are seated at the piano in their living room, belting out a nostalgic number, “Those Were the Days,” with Edith screeching off-key and Archie crooning such lines, “Didn’t need no welfare state” and “Girls were girls and men were men.”

All in the Family, based on the British sitcom, Til Death Us Do Part, was the No. 1-rated series for an unprecedented five years in a row and earned four Emmy Awards as Best Comedy Series, finally eclipsed by five-time winner Frasier in 1998.

Hits continued for Lear and then-partner Bud Yorkin, including Maude and The Jeffersons, both spinoffs from All in the Family, and both the same winning combination of one-liners and social conflict. In a 1972 two-part episode of Maude, the title character (played by Arthur) became the first on television to have an abortion, drawing a surge of protests along with the show’s high ratings. Nixon himself objected to an All in the Family episode about a close friend of Archie’s who turns out to be gay, privately fuming to White House aides that the show “glorified” same-sex relationships.

“Controversy suggests people are thinking about something. But there’d better be laughing first and foremost, or it’s a dog,” Lear said in a 1994 interview with The Associated Press.

Lear and Yorkin also created Good Times, about a working class Black family in Chicago; Sanford & Son, a showcase for Foxx as junkyard dealer Fred Sanford; and One Day at a Time, starring Bonnie Franklin as a single mother and Bertinelli and Mackenzie Phillips as her daughters. In the 1974-75 season, Lear and Yorkin produced 5 of the top 10 shows.

The late Paddy Chayefsky, a leading writer of television’s early “golden age,” once said that Lear “took television away from dopey wives and dumb fathers, from the pimps, hookers, hustlers, private eyes, junkies, cowboys, and rustlers that constituted television chaos, and in their place he put the American people.”

Lear’s business success enabled him to express his ardent political beliefs beyond the small screen. In 2000, he and a partner bought a copy of the Declaration of Independence for $8.14 million and sent it on a cross-country tour.

He was an active donor to Democratic candidates and founded the nonprofit liberal advocacy group, People for the American Way, in 1980, he said, because people such as evangelists Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson were “abusing religion.”

“I started to say, This is not my America. You don’t mix politics and religion this way,” Lear said in a 1992 interview with Commonweal magazine.

The nonprofit’s president, Svante Myrick, said “we are heartbroken” by Lear’s death. “We extend our deepest sympathies to Norman’s wife, Lyn, and their entire family, and to the many people who, like us, loved Norman.”

With this wry smile and impish boat hat, the youthful Lear created television well into his 90s, rebooting One Day at a Time for Netflix in 2017 and exploring income inequality for the documentary series America Divided in 2016. Documentarians featured him in 2016’s Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You; and 2017’s If You’re Not in the Obit, Eat Breakfast, a look at active nonagenarians, such as Lear and Rob Reiner’s father, Carl Reiner.

In 1984, he was lauded as the “innovative writer who brought realism to television” when he became one of the first seven people inducted into the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame. He later received a National Medal of Arts and was honored at the Kennedy Center. In 2020, he won an Emmy as executive producer of Live In Front of a Studio Audience: All In the Family and Good Times.

Lear beat the tough TV odds to an astounding degree: At least one of his shows placed in prime-time’s top 10 for 11 consecutive years (1971-82). But Lear had flops as well.

Shows including Hot L Baltimore, Palmerstown, and a.k.a. Pablo, a rare Hispanic series, drew critical favor but couldn’t find an audience; others, such as All That Glitters and The Nancy Walker Show, earned neither. He also faced resistance from cast members, including Good Times stars John Amos and Esther Rolle, who often objected to the scripts as racially insensitive, and endured a mid-season walkout by Foxx, who missed eight episodes in 1973-74 because of a contract dispute.

In the 1990s, the comedy 704 Hauser, which returned to the Bunker house with a new family, and the political satire The Powers that Be were both short-lived.

Lear’s business moves, meanwhile, were almost consistently fruitful.

Lear started T.A.T. Communications in 1974 to be “sole creative captain of his ship,” his former business partner Jerry Perenchio told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. The company became a major TV producer with shows including One Day at a Time and the soap-opera spoof, Mary Hartman Mary Hartman, which Lear distributed himself after it was rejected by the networks.

In 1982, Lear and Perenchio bought Avco-Embassy Pictures and formed Embassy Communications as T.A.T.’s successor, becoming successfully involved in movies, home video, pay TV and cable ownership. In 1985, Lear and Perenchio sold Embassy to Coca-Cola for $485 million. They had sold their cable holdings the year before, reportedly for a hefty profit.

By 1986, Lear was on Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 richest people in America, with an estimated net worth of $225 million. He didn’t make the cut the next year after a $112 million divorce settlement for his second wife, Frances. They had been married 29 years and had two daughters.

He married his third wife, psychologist Lyn Davis, in 1987 and the couple had three children. (Frances Lear, who went on to found the now-defunct Lear’s magazine with her settlement, died in 1996 at age 73.)

Lear was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on July 27, 1922, to Herman Lear, a securities broker who served time in prison for selling fake bonds; and Jeanette, a homemaker who helped inspire Edith Bunker. Norman Lear would remember family life as a kind of sitcom, full of quirks and grudges—“a group of people living at the ends of their nerves and the tops of their lungs,” he explained during a 2004 appearance at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston.

His political activism had deep roots. In a 1984 interview with the New York Times, Lear recalled how, at age 10, he would mail letters for his Russian immigrant grandfather, Shia Seicol, which began, “My dearest darling Mr. President,” to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Sometimes a reply came.

“That my grandfather mattered made me feel every citizen mattered,” said Lear, who, at 15, was sending his own messages to Congress via Western Union.

He dropped out of Emerson College in 1942 to enlist in the Air Force, was awarded a Decorated Air Medal, and then worked in public relations.

Lear began writing in the early 1950s on shows including The Colgate Comedy Hour and working for such comedians as Martha Raye and George Gobel. In 1959, he and Yorkin founded Tandem Productions, which produced films including Come Blow Your Horn, Start the Revolution Without Me, and Divorce American Style. Lear also directed the 1971 satire Cold Turkey, starring Dick Van Dyke, about a small town that takes on a tobacco company’s offer of $25 million to quit smoking for 30 days.

In his later years, Lear joined with Warren Buffett and James E. Burke to establish The Business Enterprise Trust, honoring businesses that take a long-term view of their effect on the country. He also founded the Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication, exploring entertainment, commerce, and society. In 2014, he published the memoir, Even This I Get to Experience.

—By Lynn Elber, AP television writer

Longtime AP television writer Lynn Elber retired from The Associated Press in 2022. Contributors to this article include Alicia Rancilio in Detroit and Hillel Italie in New York.

(15)