When you think of hospitals, you think of hallways. Here’s why we designed a hospital without them

In 2008, Rwanda was freshly tilled soil. Streets were swept, lawns were manicured, and education and health care were guaranteed. The genocide of 1994 had stripped a people of dignity and destroyed a generation of lives; the country had seen the depths to which humanity could fall. But 14 years later, after focused investments in health, education, housing, economic reconstruction, and reconciliation, Rwanda was abundant and hopeful. It was shedding histories of colonialism and ethnic division and recalibrating its future toward shared economic and social progress.

To assist in strengthening the country’s health care system, Dr. Paul Farmer and his organization Partners In Health were asked by the Rwandan government to consult. A key element of this collaboration would be a new purpose-built hospital in the remote northern hamlet of Butaro.

At that time, I was studying architecture. After hearing Farmer lecture, I asked him which architects he was working with and how I might be of service. He told me that few had ever reached out to him, and his organization was often left to design and build by itself, with just the resources it already had. He described the failure of Western “experts” as a remnant of colonial power. Outside designers working on projects for the underserved, he said, were intoxicated by modern emergency clinics in shipping containers. They never stopped to ask if people wanted to receive health care in an industrial waste product.

He also described the dystopia created by modern technology, with its ostensibly cheap, easily deployable medical care, panacea solutions to drinking water, and procedural hacks. He called this equipment “junk for the poor” and described it filling storage closets, sitting broken in hallways, or lingering, inoperable, in medical clinics the world over.

Farmer’s lead engineer in Rwanda, Bruce Nizeye, needed help designing the hospital in Butaro, and he invited me to join him there in 2008. I jumped at the chance. Most of the clinics and hospitals Partners In Health had previously built were additions or renovations to hospitals. The Butaro hospital was, at the time, the largest project it had ever designed and constructed from the ground up. The client was the government of Rwanda, and the hospital needed to address the epidemic of tuberculosis that was ravaging poor communities around the globe.

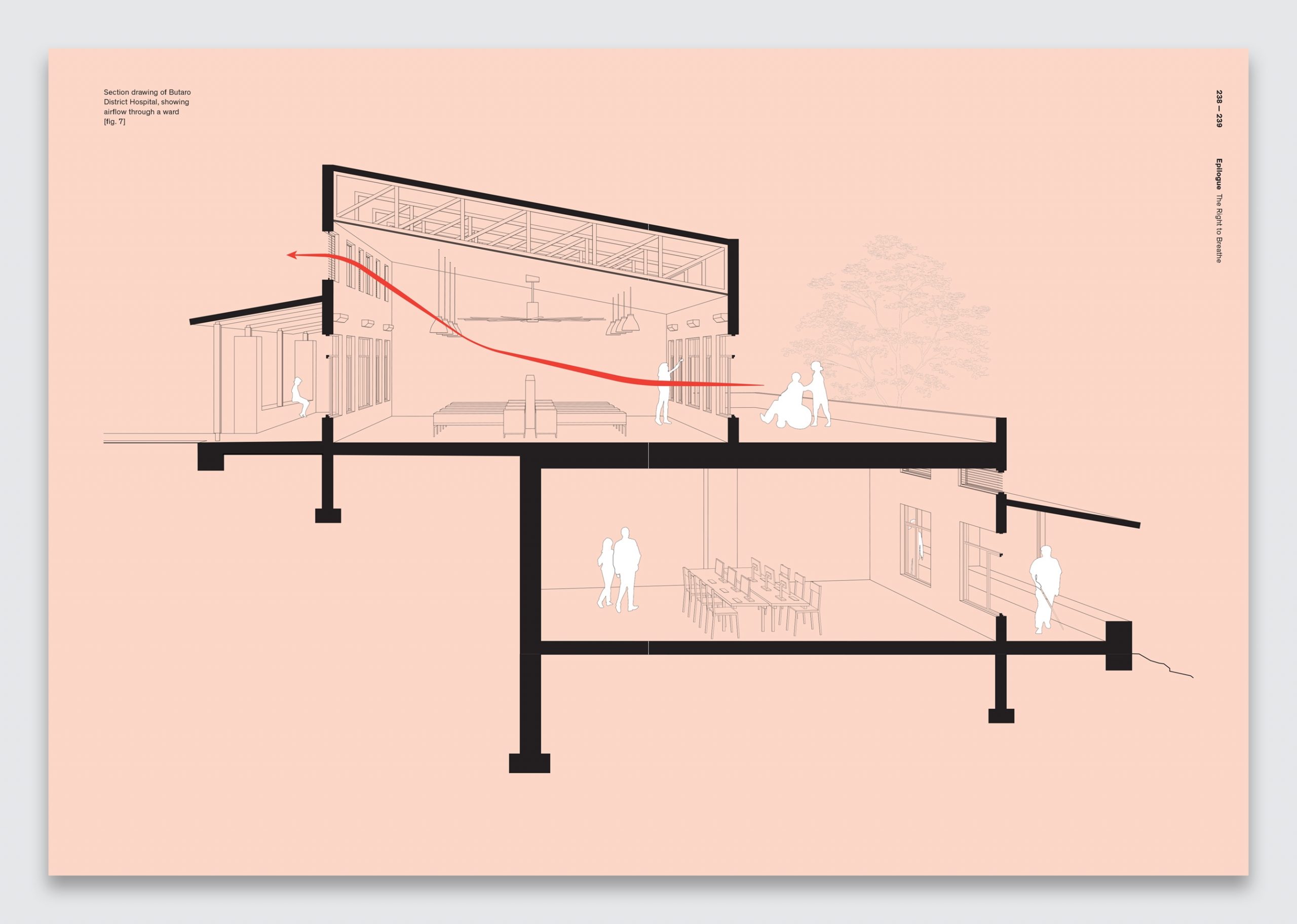

Dr. Michael Rich, an expert on tuberculosis and its multidrug-resistant variants, was then the director of Partners In Health’s Rwanda operations (through its sister organization Inshuti Mu Buzima) and an architecture junkie. Hospital hallways, he explained, were the major problem in the transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Patients waiting in these spaces without windows or airflow would cough on each other, become coinfected with drug-resistant variants, and then bring them back to their communities. In the hallways of hospitals, buildings meant to heal, the epidemic had begun.

“We have been trying to design hallways out of hospitals for years,” Rich told me. Naïvely, I asked, “Shouldn’t a modern hospital use a mechanical system to ventilate its spaces?” Like a patient teacher, he explained that mechanical systems never work as designed. And sometimes, he said, they are too expensive to maintain. When they break or are turned off for budgetary reasons, the spaces have worse airflow than those with simple windows or outdoor waiting areas. Better mechanical systems do not meet patients where they are.

Dr. Edward Nardell, another tuberculosis expert at Partners In Health, pointed me to a study in Peru that showed how older, colonial-era hospitals, built with generous windows, tall ceilings, and open-air waiting areas, were better able to prevent the transmission of tuberculosis than newer ones designed to keep mechanically conditioned air from leaking out. Nardell also introduced me to Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Hospitals and her spatial strategies to increase airflow and reduce disease transmission. I realized that there were universal principles of building function that transcend culture, context, and time. We sought to locate more of these truths and insert them into the design of the Butaro hospital.

The Right to Breathe

We took Rich at his word, and proposed a hospital without hallways. In the new structure, all patient, staff, and public movement and waiting takes place outdoors. Rwanda’s temperate climate allows for comfortable exterior waiting throughout most of the year, but when it rains, covered outdoor areas provide respite. Exterior hallways necessitated a distributed multibuilding design rather than a centrally loaded institution, and the buildings had to be thin (so air could move through them). Doctors would walk between buildings dispersed in a campus setting, so we created covered pathways surrounded by lush landscaping and gardens to brighten their journey.

Elevators often break, and in rural areas the maintenance required is too specific for proper upkeep. We needed a facility that would be accessible without elevators, one that a patient in a wheelchair could fully traverse. Rwanda’s zigzagging hillside footpaths were a useful precedent; we layered the hospital across the crests of a hill to ensure that multiple stories would be accessible at ground level. This had the additional benefit of leaving space for future campus growth.

The trend in both infection control and patient experience was to isolate patients in single rooms. But in rural settings, Rich told me, patients were dying more often in isolated rooms because there were not enough staff to monitor them. Without complicated monitoring devices, it was necessary to have a visual relationship between the nurses’ station and the patient. We designed open wards with nurses’ stations in the center, low walls to ensure the visibility of the entire room and all the beds, and few corners to block the view between staff and patient. Glass-doored isolation rooms for actively contagious patients are located at the end of each ward. Adjacent bathrooms are equipped with their own venting and entrances off the wards to reduce the spread of odors and bioaerosols.

Nightingale’s design principles were based on wards that could hold a carefully balanced load of 20 to 30 beds: no less, no more. In Rwanda, we saw wards designed for two dozen patients holding well over 30, sometimes with two to three people per bed or with patients lying on mats underneath. With few medical facilities in the country, this was understandable: doctors were trying to use all the available space. But we knew how dangerous overcrowding and unregulated scale could be, and we wanted to ensure that the wards in Butaro would not overfill during times of stress to the system.

Nightingale’s prescriptions, I learned, defined a parametric relationship among people, spaces, and services. When one of those elements is out of balance, the system can break down and patients can get sicker. To target overcrowding, we amended the Nightingale ward slightly, replacing the central hallway with a half-height wall. Patient beds project out from this central wall, facing the windows, and the pathway encircles the ward rather than cutting through the center of it.

This provides three complementary benefits. First, with an immovable wall in the center and smaller hallways on the perimeter, staff can’t overfill the ward without disrupting the nursing rounds. In this way, we designed against the downside of flexibility. Second, this central wall consolidates electrical outlets, call buttons, and oxygen sockets, which are placed in the headboard. Its colored panels are removable to allow for the addition of future systems and for repair.

The third benefit taught me about the deeper role of architecture. With their beds oriented to face the windows, patients can see the breathtaking landscape outside. Scholarship has shown that a simple view reduces patient stay times and pain medication requests. Plus, it was quite obvious that it would be preferable to look out a window rather than gaze at a roomful of other sick people. With beds no longer arranged along the periphery of the ward, we were able to increase the window sizes, lowering the sill below headboard height, and thus bring more light, views, and air into the space. This simple move demonstrated that when architectural design is human centered, it can be in harmony with function, form, and experience.

“With limited resources,” Farmer once said to me, “people get resourceful.” This seemed to be the case in Butaro. The new ward design, now called the Butaro ward, is written into national guidelines, and it has been replicated in hospitals throughout Rwanda and beyond. I am sure we will see the Butaro ward adjust and recalibrate as new services and systems take over these hospitals. But I was reminded that when doctors fight for their patients’ access to health care, they are also fighting for their right to breathe clean, uncontaminated air. Nightingale changed a lot of things, but most important to us was the revelation that architecture is an essential, rights-based discipline. I learned this on that hill in Rwanda.

Excerpted and adapted from The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignity, an accompanying publication for the Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics exhibition, on view at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through February 2023

Michael Murphy, Int FRIBA, is a founding principal and executive director of MASS Design Group, a collective of architecture and design advocates dedicated to the construction of dignity. MASS is the recipient of the 2022 AIA Architecture Firm Award.

(24)