Why Designer Daniel Arsham Won’t Work For Anyone But Himself

Eight questions for the New York-based artist, whose latest solo exhibition opens at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati this week.

Daniel Arsham is a designer-of-all-trades. One half of Snarkitecture, the experimental art and architecture firm he founded with Alex Mustonen, he also runs his own art studio, and is working on a new film project premiering at the Tribeca Film Festival next month. Arsham’s new solo exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Remember the Future, features 3,000 sculptural objects. His latest artistic foray involves casting modern technology—cell phones, microphones, Nintendo controllers—in geological materials like ash, crystal, and obsidian. Co.Design spoke with the designer before the opening about his earliest design work, his worst job, and more.

What was the first thing you ever designed?

I remember trying to reverse-engineer the design of the house that I grew up in, trying to make architectural drawings on graph paper of that house. It was like trying to understand that space as a 9-year-old. I always thought I would be an architect. I have come back to that in some ways, but I did that through the formation of this practice with actual architects. [Arsham’s Snarkitecture cofounder, Mustonen, has an architecture background.] I never had the patience for the meticulous aspects of that profession. I do have some old drawings that my father recently uncovered of buildings and clouds sort of in the same context as works that I’ve made more recently. It’s sort of an uncanny thing to find those works again from my early teenage years.

What is your daily work routine like?

The studio opens at 10 a.m. I usually get there at like 8:30 a.m. I have a couple hours of work before the whole crew arrives. I have set up the studio in a way that I can move between all the disciplines I work in, in the same space. My studio is in there, , and my new film company is in there. I may work on a painting for an hour or two, then I may go work with Alex on a new building, then sit with my editor working on a new film.

What is your biggest challenge as a designer?

Dealing with people’s expectations of time. A lot of work that I make is not something that can be made quickly. The exhibition I’m opening in Cincinnati, I’ve been working on for almost two years. There is an expectation of rapid design and realization of things that isn’t quite the world I can operate in. Things that I’m working on now are for next year and into 2016. I’m never late, but I’m very realistic about the timeline at which things can be made.

What’s your favorite thing you own?

I have this lens which is a Leica Noctilux. This lens is very special because it’s the largest commercial aperture lens you can get, meaning I can shoot in very low light. I like that environment, shooting in near darkness.

What is the worst job you’ve ever taken, and what did it teach you?

I was an art handler about 15 years ago, and I had to deliver a very large Basquiat drawing to a client. The drawing was too big for me to lift by myself, and I refused to move it because I didn’t want to damage it by trying to move it myself. I was fired from that job. That was the last time I had any job [working] for anyone else. [I learned] that I like to do things in a specific way to make sure they’re done correctly, and I’m not willing to sacrifice that for anything.

If you weren’t a designer, what would you be, and why?

A fighter pilot or an astronaut—you’re getting my 12-year-old self. I’ve always been fascinated with space and aeronautics. I’ve brought it into my practice: One of the films I’m working on now takes place in a future airplane cockpit that I designed and built.

What do you think is the biggest challenge facing the world that design can help solve?

I think the world is a very lopsided place right now in terms of health, housing, economy, and information. I mean, certainly design aids in all of those aspects. I don’t think it’s done a particularly good job of doing that, but there’s some interesting projects that I think hopefully will come about in the next 50 years that will solve that.

But I don’t have particularly high hopes for the direction that things are heading. People are creatures of habit, and when I see things like this massive wave power generator that they just unveiled in Australia, and I wonder why that isn’t powering everything. It baffles me.

In some ways, the film that I’m working on has some relationship to that. It portrays a world made to look like objects uncovered on some sort of future archeological site. I think my job as an artist is to create that tension, to allow people to look at these objects from their contemporary lives as if they’re viewing them from the future.

What piece are you most excited about in your new exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center?

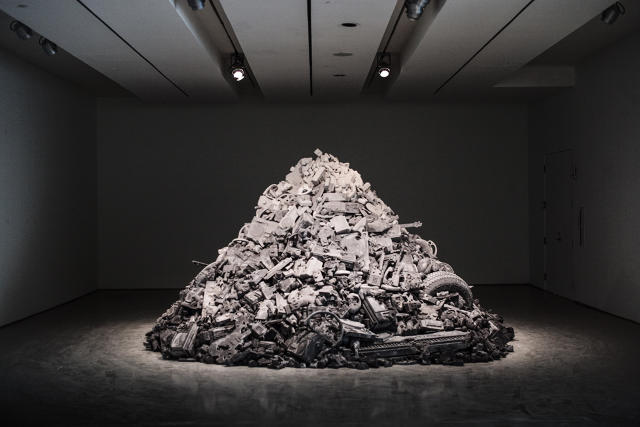

There’s a very large pile of objects like the objects we were just talking about, from this heap of technological items, things that we all remember, things that we have used, things that many of us have owned. The scale of it is quite monumental: It’s about 9 feet tall. There is the first Mac laptop, old phones, lot of things related to communication.

It can be a dark reflection, because these items appear as if they have survived some cataclysmic event, but we’re not there yet. We’re looking upon a possible future.

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(261)