And The Brand Played On: How Yesterday’s Tech Icons Live On Through Licensing Deals

The owner of a new rainbow-emblazoned camera peers through its tiny viewfinder and pushes a shutter button. A few moments later, a photo emerges. As baby boomers might surmise, the camera carries the brand of Polaroid, the company at which this camera’s instant photo technology was developed. But this isn’t 1974. It’s 2016.

Polaroid spun out the instant print technology this camera uses years ago into a company called Zink. And the camera—the Polaroid Snap—is actually produced by a company called C&A Marketing, a licensee of the Polaroid brand.

Licensing was a $241.5 billion industry in 2014, according to the Licensing Industry Merchandisers’ Association. Some of its major players include celebrities, sports leagues, characters, and franchises that span apparel, food, furniture, video games, and toys. That last area is a particularly fertile ground for licensing: Shop for a Lego play set these days, for example, and you’ll be dazzled by the variety of intellectual property the company has licensed brick by brick, including Star Wars, Batman, Angry Birds, Marvel heroes, The Hobbit, Minecraft, and on and on.

In electronics, licensing has also become more commonplace in the past few years as companies have sought to leverage their brands outside of their core categories or geographies. In 2008, Philips turned its Philips and Magnavox brands over to Japan’s Funai for TVs in the U.S. The deal eventually soured. However, Toshiba is following suit with Taiwan’s Compai. And Hong Kong’s Binatone licenses the Motorola brand for a range of accessories.

In many of these instances, the transfer of a brand from its originator to a licensee goes off without a noticeable hitch. But aggressively licensing long-defunct brands can take them to strange new places. Take Crosley, a brand that adorned radios, refrigerators, and cars in the 1930s and 1940s and has more recently helped lead a renaissance in retro-themed turntables. Bell and Howell was a leading manufacturer of film projectors for much of the early 20th century. Now the brand lives a dual life, as both a company providing postal-handling equipment and services and the name on such As Seen on TV products as ultrasonic pest repellers and penguin-styled portable humidifiers.

Instant Photography’s Delayed Rebirth

In the aftermath of digital photography, Polaroid declared bankruptcy in 2001. More than a decade later, its old rival Kodak would do the same and exit the consumer camera business. Unlike Kodak, though, Polaroid did not have a significant commercial business on which to lean. After seven years of changing holding company names and ownership, Polaroid resurfaced as a company dedicated to licensing its brand in the late 2000s. And like a spirit reaching enlightenment, it has transcended the bounds of its mortal category to become one with a diverse universe of gadgets.

The road back has not always gone smoothly, particularly for licensees that really share the brunt of the licensing risks. Explains Chaim Pikarski, executive vice president of C&A Marketing, “I’m not saying that every single person in the population knows that Polaroid is relevant and has products out there, but it’s much less frequent that people say, ‘Oh, they’re still in business?’ I don’t get that so much anymore.”

Some products that bear the Polaroid name—the Snap camera and the tiny Zip Bluetooth photo printer—have direct ties to Polaroid’s instant-photography legacy. Others, such as the inviting Cube+ action camera, extend the brand to younger consumers by leveraging its imaging cred. Considered “hero” products, their design has benefitted from both licensor and licensee investment and partnership with a leading design firm.

But other Polaroid-branded products—including TVs, tablets, and smartphones—might have those who knew the original Polaroid scratching their head. What, for example, is the value of the Polaroid brand on a Bluetooth speaker, a category saturated with brands both firmly entrenched and completely unrecognized? Polaroid CEO Scott Hardy says that smartphones are today’s default cameras, and that it’s also necessary to pursue accessory products to round out support for that bigger prize.

Lengthening A Legacy

Polaroid’s success has been a model for Technicolor, the color experts most of us know from a credit at the end of movies. However, Technicolor is also a brand licensor that owns the RCA and affiliated brands such as Thomson, Victor, and ProScan. Like Polaroid, RCA had a long history of innovation that included the first color television. Today’s RCA televisions are produced by a licensee called Activeon, which has used its own brand for action cameras. It competes with Polaroid in the TV, tablet, and smartphone categories.

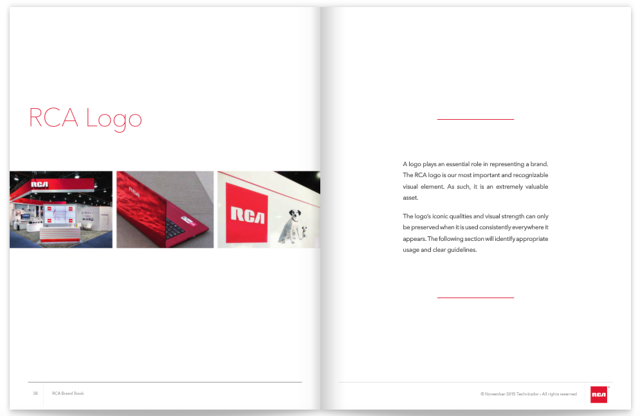

As with Polaroid, the new stewards of the RCA brand have distilled it to traits that include innovation and value; its executives talk about licensed products as their own, and the company distributes a brand book that lays down the law about how the RCA brand may be discussed in copy and used on packaging. The brand, which plays well at mass retailers, targets young families and relies on intergenerational connections to keep its once-pervasive name going.

Indeed, brands such as Polaroid and RCA represented innovation to the analog generation, but making them resonate with consumers who grew up in the digital era is critical to their continued marketplace value. That’s a big challenge in a world where headphone brands such as Skullcandy and Beats can be built quickly among younger consumers.

Closing The Generation Gap

“Because our brand was in its peak during the late 80s to mid-90s, we were more appealing to the gen X generation and baby boomers,” says Hardy, who was at Polaroid when it still manufactured cameras and film. “You don’t want to be a brand as old as Polaroid or older and licensing just to collect money instead of building a thriving brand that’s relevant.”

“As you can guess, the older you are, the more aware of the [RCA} brand you are,” concedes Pam Kunick-Cohen, head of band management at Technicolor. “Even with that, it’s still pretty strong relative to other consumer electronic brands.” For Polaroid, social media has been key to reaching a new generation as its name now sprawls across more than 60 products including headphones, hoodies, tablets, and turntables. Polaroid’s past still means something to younger people: The original icon of Instagram, the wildly popular app that embodies 21st-century photo sharing, was inspired by the Polaroid OneStep camera that debuted nearly 40 years ago. Speaking of Polaroid-branded T-shirts sold at Urban Outfitters, Hardy notes, “We have this retro hipster cool factor.”

Product Proliferation

While both Polaroid and Technicolor seek to expand aggressively, questions loom about their strategies. Both brands already compete in the largest device market, offering branded Android smartphones. How far afield from their naturally associated categories can they stretch? Every time a licensor expands into a new category, it assumes a number of risks that include further brand dilution, potential concerns about quality, and opportunity costs. The companies know about these dangers: That’s why Polaroid’s manufacturer due diligence, for example, includes factory inspections.

The companies’ focus on licensing also doesn’t isolate them from the category consolidation that’s hurt even big players such as BlackBerry, Nokia, and Motorola in recent years that the smartphone and other smart devices has wrought. Polaroid is already diversifying with offerings such as an online service called Polaroid University that offers online classes on better picture taking for $20 per year.

Kunick-Cohen says RCA has always had been elastic, at least compared to Polaroid’s photography-focused brand. She notes that, in the ’70s and ’80s, the company had a history of going across products and categories. Speaking of its success in tablets, she says, “There are other accessibly priced products at retail, but people feel that the RCA brand brings a level of quality, confidence, and customer service.”

During the 2015 holiday season, Walmart.com offered a 7-inch RCA tablet bundled with a companion keyboard for only $39. While that doorbuster price may have been associated with the retailer’s typical aggressive discounts or a desire to establish the brand in a new space, it raises the question of how much value the RCA name carries, especially given that lesser-known tablets commanded a higher price. But RCA, like Polaroid, is seeking to build a reputation that isn’t just about attractive price tags. Its just-announced 4K TV sets for example, are among the first to offer to integrated Android TV functionality.

What’s next? Polaroid is already venturing into categories such as 3-D printers and drones. Technicolor says that TV continues to drive the RCA brand, but virtually anything related to consumer technology is fair game. As for Polaroid, Hardy says, “We view our role as curators of innovation.”

Fast Company , Read Full Story

(30)