Andy Warhol’s portrait of Prince is about more than fair use law—it’s about the future of creative freedom

The internet has opened access to culture. Billions of web pages build on the art, images, music, film, television, and writing of the past.

This explosion of content leads to tough questions over ownership of creative work and exclusivity of use. The highest court in the land may soon try to better define the limits of free use, or the right to remix previously published work.

On October 12, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. The case addresses when artists or writers may quote from and comment on others’ works. While quotation in everyday speech usually refers only to text, as a legal matter paintings, photographs, and architectural forms are also subject to quotation.

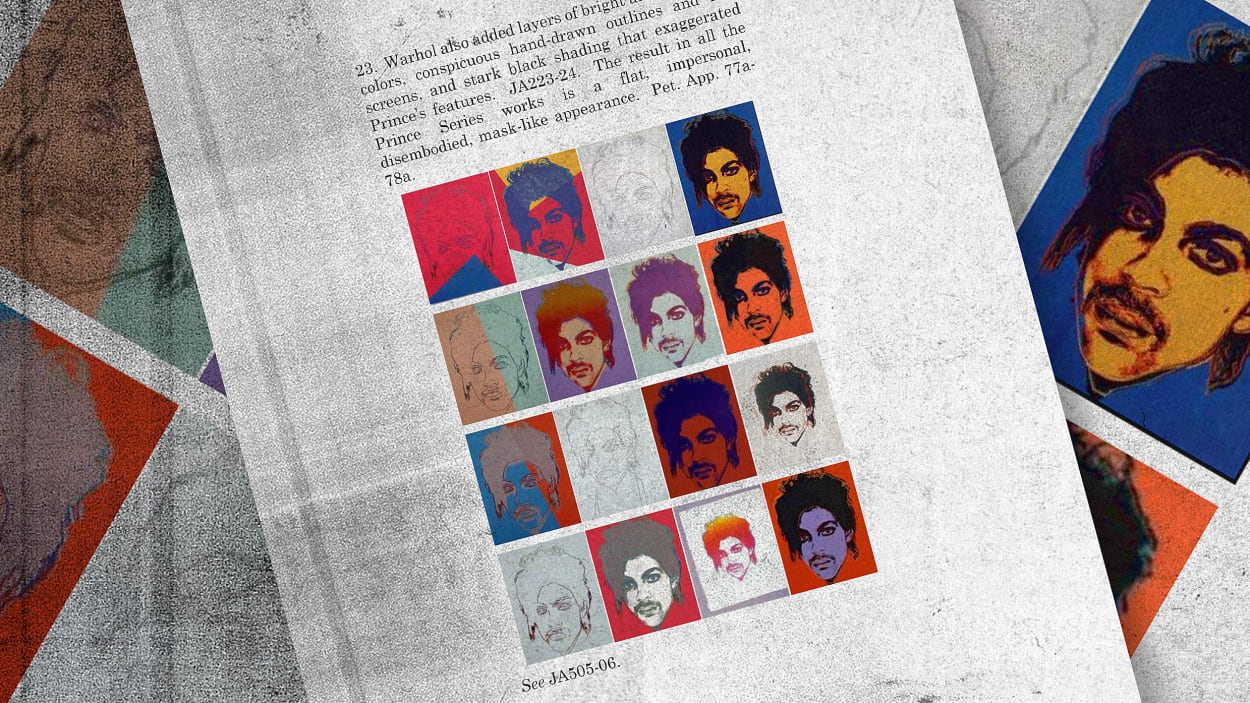

In 1984, Warhol created 16 variations of a portrait of the singer Prince based on a photograph taken by Lynn Goldsmith. For a payment of $400, Goldsmith granted Warhol permission to use the photograph to make a sketch or painting to illustrate a Vanity Fair article on the success of Prince’s recording Purple Rain. The license allowed no other uses.

The foundation now owns the paintings, prints, and sketches Warhol made of the photograph, and profits handsomely selling them to museums and licensing them to others.

My research often deals with how the right to express oneself can be harmed by narrow interpretations of the law. I focus on the First Amendment, which guarantees free speech, and the fair use privilege, which moderates the effect of copyright law on artists and writers by allowing a certain amount of copying.

In the Goldsmith case, the Court is being asked to correct what I think is an important error in copyright case law—the assumption that deriving any value from another’s copyrighted work is an infringement that is automatically “unfair” unless one can meet the difficult burden of proving the use has no impact on the value of the original.

Intellectual property shapes the international economy. The U.S. market has an outsize effect on creators around the world. So the way that the Supreme Court defines fair use affects everyone from journalists and politicians to musicians, photographers, and streamers in the U.S. and abroad.

Future of fair use is technical

Enforcement of copyright in the digital world takes many forms.

The rise of file fingerprinting and filtering algorithms means online creators face an often relentless barrage of threats when attempting to quote other creators’ works. These can take the form of copyright strikes, which can lead to account suspension and termination, and takedown requests. Channel demonetization happens when YouTube blocks a creator’s ability to make money by refusing to share advertising revenue. These techniques result in works being deleted from websites without a trial or much in the way of due process.

YouTube itself and other platforms like Facebook, where images and videos can be shared, might have been banned all along had the Supreme Court not clarified in the 1980s that new technologies that have a mix of lawful and copyright-violating uses are not necessarily illegal.

The Court also issued a double-edged ruling on fair use nearly three decades ago in a case involving the rap group 2 Live Crew’s “Pretty Woman,” which spoofs a Roy Orbison song. While helpfully clarifying that parodies and harsh attacks on copyrighted works can be a fair use, many legal observers, myself included, feel that the opinion undermined the text and intentions behind fair use. Specifically, it required that fair users vary their “meaning or message” starkly from the original work, and imposed a difficult burden of proof upon them.

Fast-forward to arguments made before the Court in October 2022. The lower court judgment being reviewed by the Supreme Court concluded that because Warhol’s modified print of a photograph of Prince looked similar to and derived value from the photographer’s original version, it was a copyright infringement. The court saw it as infringing on the photographer’s rights despite Warhol’s intention to place the photograph into a new artistic context as a comment on celebrity culture—as his 1962 soup can and Marilyn Monroe works did.

Other federal courts had ruled that a subsequent creation deriving value from and sharing the message of a previous work is unlikely to be a fair use. This presumption applied even if an initial work’s textual or audiovisual components are altered in major ways by the new work, whether it is a news report on a book, a remix of comic book characters or song lyrics, a guide to a film or television series, or a new level of a video game.

Judges and justices who opposed this trend argued that the First Amendment was being trampled and that fair use was endangered.

The Warhol Foundation argues that fair use may exist in diverse circumstances ranging from postmodern art to showing corporate logos in films, displaying street art in music videos and making unauthorized use of photographs in newspapers. The argument gained traction among the Supreme Court’s justices, with several suggesting during their questioning that artists and other Americans should be able to shed new light on existing images and words, and not simply as parodies or critiques.

My research has traced how a particular brand of economics and a set of sociological assumptions have distorted the free speech right to engage in fair use expression. In place of an older libertarian system that permitted authors to put text and characters from prior authors’ work into new creations, 20th century courts developed what I consider to be a restrictive and arbitrary standard that quotations must serve different meanings and purposes. This departs from the language and intentions behind the Copyright Act of 1976, which refers to “comment” on existing works as being potentially fair, in addition to criticism or ridicule.

However the court rules, fair use will continue to be with us. As law professor Lawrence Lessig once observed, people inevitably imitate the tales and images or music that they admire or grew up with. That impulse will be impossible “to kill it off once the public has tasted the freedom to create and share what they create with others via the web,” Lessig wrote.

A decision from the court is expected in May or June 2023. With the justices’ questioning bringing out serious problems with the lower court ruling, a resolution in favor of subsequent artists’ rights could help writers and filmmakers as well. It will help decide whether a few unlucky creators will be hit with large judgments, and millions more creators will be deterred from expressing themselves or may have their work automatically filtered by faceless censors.

Hannibal Travis is a professor of law at Florida International University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

(37)