London’s infamous sewer blockage now has its own disgusting live-stream

When I first saw the titanic fatberg that was found blocking a London sewer in September 2017, I felt so nauseated that I had to immediately close the webpage.

Except I didn’t. I kept watching–as did millions of other people on the internet–as more photos and videos emerged of workers in hazmat suits trying to break apart the fatberg, which as its name suggests, is a lump of fats and waste products that clog sewer systems.

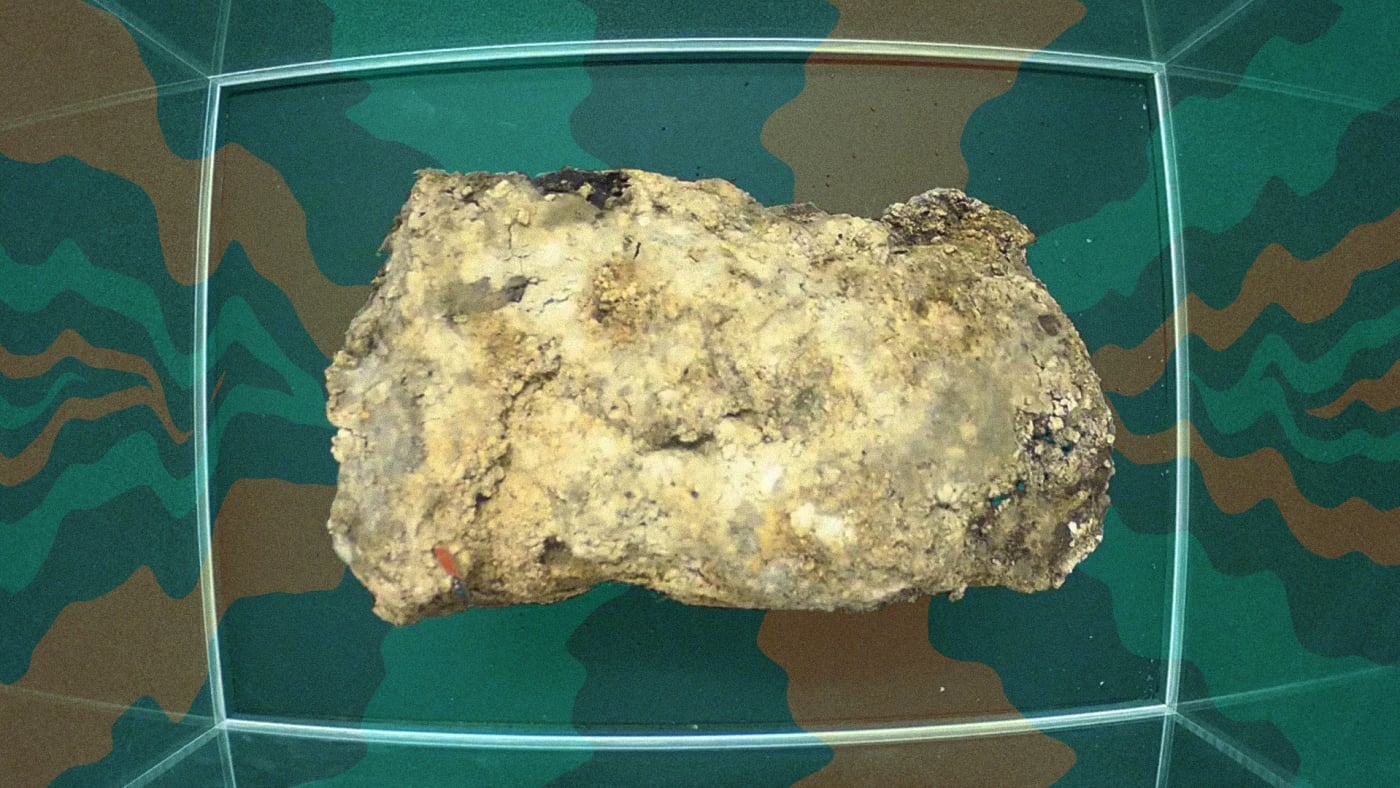

Something about this disgusting monument to our cities and ourselves captured our attention. And the Museum of London, apparently, took notice. The museum’s curators took the initiative to put a festering piece of the fatberg in a glass case for visitors–and if you’re not local, it’s streaming it live. According to The Guardian, the fatberg has “hatched flies, sweated and changed color while on display.”

The Whitechapel Fatberg–as Londoners christened it–was the result of years of accumulation of condoms, diapers, tampons, and wet wipes flushed down millions of toilets along with organic substances. Through the magical chemical process of amalgamation, all these elements attracted each other, glued by oils, fats, and poop, solidifying over time into gigantic masses as hard as concrete (hence the “fatberg” name). According to Matt Rimmer–the head of waste networks of Thames Water, the company that manages the water and sewage system in London–the fatberg was “a total monster” and it took a “lot of manpower and machinery to remove as it’s set hard.” How monstrous? The thing weighed the same as 11 double-decker buses (130 tonnes) and was as long as two soccer fields back to back (820 feet).

As the workers slowly disintegrated it, the Department of Conservation and Collection Care at the Museum of London thought it would be a good idea to save some of the literal crap for posterity, creating an exhibit for the phenomenon. Talking to Ars Technica, collection manager Andy Holbrook said that they always knew they had to do it. “[It] kind of appeals to the child-like sense of things that are gross,” he said. The live-stream was simply the next logical step.

And he’s right. It is fascinating. I watched for five minutes, hoping that some kind of gross critter will slowly emerge, thinking that no one was watching. But of course, we were.

(51)